The UK faces a future of devastating floods, like the one that hit Boscastle three years ago. But instead of fighting them, some people are suggesting we learn to live with them.

It’s quickly becoming clear that global warming will not just mean hotter summers for Britain. For starters, try a quick flashback to the deluge that devastated the village of Boscastle in Cornwall two years ago. Now multiply that local catastrophe by the land area of the UK and your find that £237bn in assets lie at risk from flooding, and that includes 10% of all existing homes, housing 5 million people.

These figures do not come from doom mongers. They appear in the opening paragraph of the government’s planning policy statement PPS25: Development and Flood Risk – a tightened-up redraft of the communities department’s 2001 report.

Along with global warming, flooding has risen up the agenda of several government departments and quangos, and of private developers, too. As in fire prevention, planning for flood risk requires that private development teams work closely with public authorities. Unlike fire prevention, though, many solutions that are currently deemed acceptable may eventually be negated by inexorably rising sea levels, that is.

The Association of British Insurers has laid down guidelines to minimise flood risk over the past three years, which developers flout at the peril of rendering their buildings uninsurable. The Environment Agency and the Construction Industry Research and Information Association (CIRIA) have published guides to resisting and repairing flood damage.

In a couple of months, all these will be topped by new Building Regulations on flooding. Last October the Environment Agency was appointed a statutory consultee in flood zones, where it uses the redrafted PPS25 as its bible. Councils are now required to consult the EA on all planning application in flood zones.

All these organisations have good reason to take flood risk seriously. Global warming is widely predicted to cause rising sea levels and violent storms, which can cause flooding not just from the sea but also from rivers, reservoirs, sewers, and surface water drains. The government is also piling on risk by committing itself to building 120,000 homes in the tidal floodplain of the Thames estuary by 2016. This area comes with the additional problem that its existing flood defences, including the Thames Barrier, are only predicted to hold out until 2030. The Environment Agency has set up a taskforce, Thames Estuary 2100, to investigate what extra safeguards can be adopted after that.

Defence is not the best form of attack

The redraft of PPS25 reinforces but does not radically change the communities department’s strategy of managing flood risk. According to Kevin Knott, water engineering expert at Faber Maunsell: “It’s all about risk to people rather than risk to buildings.”

Accordingly, the guide encourages the development of buildings for vulnerable groups, such as schools and homes for the elderly, outside flood zones.

But, as PPS25 warns, we cannot just raise defences indefinitely. David Ramsbottom, the director of flood management consultant HR Wallingford, says: “The higher you build the defences, the bigger a catastrophe you face.” PPS25 also introduces an “exemption test” that might allow vulnerable buildings in higher flood zones if no alternative sites can be found.

Even so, there is little sign that PPS25’s strictures are antagonising developers. Andrew Whittaker, the Home Builders Federation’s (HBF) head of planning, says: “We’re very supportive of the new guidance, because we don’t want to build in flood zones anyway. And the new sequential test makes common sense, as it puts the onus on local authorities to examine flood zones before they allocate housing to them.”

What the HBF is less keen on is the Environment Agency’s new powers to issue “holding objections” on planning applications that buys time for further investigation. “Because the agency is short-staffed, this engenders a considerable delay,” says Whittaker. “In effect it vetos an application.”

The PPS and other construction guides also propose strategies for coping with floods themselves, when they happen. In neighbourhood masterplans, green spaces can be assigned to lower lying areas where they can absorb flooding with little damage. These can often serve as attractive nature reserves.

As for buildings prone to flooding, they can be safeguarded by either of two strategies. The first is known as dry-proofing or flood resistance. This entails sealing the building with impervious barriers built into the structure.

Wet-proofing or flood resilience is the second strategy. In the event of a flood, water is allowed to enter the building, but finishes, fittings and building services are specified to resist damage. Stephen Garvin, the construction director of BRE Scotland and a flood damage expert, says: “Concrete can work because it doesn’t tend to absorb water. Timber doesn’t respond well to high moisture content, but it can be protected by treatment.” Knott adds:

“Cabling and building services should drop down from the ceiling so that you can isolate them from above.”

Another resilient approach is to raise habitable spaces to first-floor level, above car parking or other spaces that can withstand flooding.

Amphibious cities

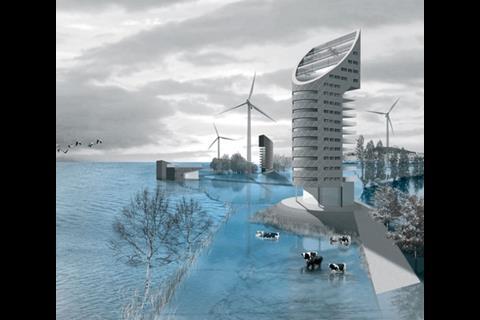

But looking decades ahead, long-term climate change is likely to demand more radical flood protection. Barker and Coutts Architects is carrying out a research project: Long-term Initiatives for Flood-risk Environments, for the Department for Environment’s Making Space for Water programme. Robert Barker and Richard Coutts propose floating or demountable homes and high-rise apartments, so daily life can continue while encircled by floodwaters.

The future has already arrived in the Netherlands, where 70% of the land is below sea level. Here developer DuraVermeer is devising an “amphibious building” that rises and falls with the tide like a houseboat but can rest on concrete piles when the water completely recedes.

Kees van der Sande of London-based Kiran Curtis Architects, which works closely with the Environment Agency, doubts such radical amphibious solutions will ever reach the UK. He dismisses such visions of the future as “a blind alley because there isn’t that pressure on land in Britain, and a waste of money because they take no account of developers’ risk”.

Cities floating like lilypads may be a fantasy, then, but the revised planning guidelines provide developers and architects with a lot of fish to fry.

Postscript

Click here to have your say on our “what you think” discussion page.

No comments yet