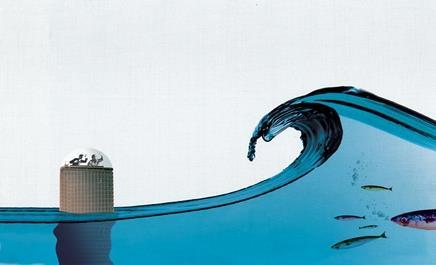

The wave of redundancies has mainly engulfed junior staff so far, but now the water is rising up to the boardroom

First it was the workers. Now bosses are starting to suffer too. During times of economic hardship, those on the bottom deck are usually the first to be sucked under, but as the current crisis deepens, management level are seeing the water lapping at their trouser bottoms. Even company directors have reason to be wary.

“It’s a bit of nightmare, to be honest,” says David Jackson, managing partner of construction and engineering headhunter Stone Executive. “Most large construction companies are looking to cut back and one way of doing that is by letting senior staff go. By the same token, companies don’t want to take on any new senior staff, so it has become a vicious circle.”

Senior executives entering the job market now will be startled by how quickly the balance of power has shifted from candidate to employer. “A year ago there were more jobs around than there were good candidates and it was hard to get quality people,” says Mark Heald, director of construction and property at recruitment firm PSD Group. “If you did persuade someone to resign, the company they worked for would try to hold on to them with promises of promotions, more money and better working terms. Now there are a damn sight more candidates than there are jobs.”

The turning point came very suddenly last autumn, according to Robert Smith, chairman of the Management Recruitment Group. “Until October or November the recruitment market was fairly buoyant. Then we had the first wave of redundancies and a lot of people came onto the job market – from the housing sector in particular.”

These executives with a housing background will find it hardest to find new positions – not only because their sector has been worst hit, but because many will have little experience of other areas.

“A lot of the senior executives, managing directors or regional managers in the housebuilding sector joined their companies from school,” says Jackson. “Some have come up through the ranks from being a bricklayer and ended up as managing director, so all their experience has been in housebuilding. It’s very hard for them to diversify, because moving into the commercial building industry requires a different set of skills.”

Across the board, newer managers are most likely to face the chop. This is because it is easier to make relatively new members of staff redundant and they are due smaller pay-outs. Smith says many of the executives who have approached him looking for new positions had only been in their jobs for a year or so.

But long service is not always a protection, as Lesley Fletcher of real estate headhunter Thomas Cole Kinder confirms. “We have seen some really good people with fantastic experience of working with solid blue-chip companies being let go,” she says. “Sometimes it is the older, more experienced people who go because the overhead of keeping them on is much higher than paying them a standard redundancy package.”

The other side of the coin is that managers who could command high payouts if they were made redundant are reluctant to move around, which is further freezing the recruitment market.

A lot of senior staff in housebuilding have come up through the ranks from being a bricklayer, so all their experience is in housebuilding

David Jackson, Stone Executive

Heald recalls a recent client who was offered a senior position with a salary of about £180,000: “He was due to accept, but then got the willies. He said, ‘I’ve been there nine years, if I get made redundant I’m due nine years’ redundancy pay, whereas if I start at a new company I’ll be the first out’.”

What next?

So how do top-level construction professionals cope with finding themselves back in an increasingly competitive job market? Rachel Brushfield is a career strategist with talent management consultant Energise, who helps managers “reinvent” themselves. “Being made redundant is a rejection and it feels very personal,

whether someone has been with a company for years or just a few months,” she says. “But everyone has a transferable skillset. It’s important to take a step back and look at yourself in terms of skills, qualities and experience and how you could apply those in a different context.”

She tries to convince her rejected executives that moving on from a company can be a positive thing. “If you are in a job, you can just be cruising. Sometimes people end up doing something much better for them elsewhere and they probably wouldn’t have changed if they hadn’t been forced to.”

Vaughan Burnand, former chief executive with Shepherd Construction points out that most people departing from executive roles are in a good position to explore other possibilities – not least financially. “If you depart from a company at a high level you tend to receive some financial impetus to do so. Having financial independence means you can pursue a number of things. You can enter into a plural career where you can join the trust of a health authority for six grand a year or do some work for the ODA or whatever. You can start your own consultancy, your own business or a number of businesses. There are other entrepreneurial opportunities too.”

Since parting company with Shepherd in October, Burnand has done some consultancy work and taken a non-executive chairmanship with a small company in the construction sector, but is still mulling over his options. “My job was a good one and well paid and I would have stayed there until I retired, but we had a particular situation and in some ways it’s possibly the best opportunity I could have,” he says.

“If you’re looking for someone good at a top level it’s probably going to take about six months to find someone suitable so it’s not unreasonable for an executive to take that long to get himself back in work.

That’s why you get such a big bulk payment when you leave these positions. But also if you’ve reached an executive position generally you’re in the 45-plus age bracket, you’ve got a lot of experience and you really need to know what you want to do. You may not be best suited to jumping back in the frying pan.”

If you have reached an executive position you’ve got a lot of experience and you may not be best suited to jumping back in the frying pan

Vaughan Burnand, former Shepherd boss

A readjustment

The positive side of the situation from an employer perspective is that those who can still afford to take people on have a greater pool of talent to choose from, as Stephen Reilly, recruitment manager at Rider Levett Bucknall, points out. “It’s been a strange market because for the past three or four years there has been a shortage of skills,” he says. “I think the current market has redressed the balance a bit. Now if there are people looking for work, a lot of them will be really high-flyers who may have been caught at the end of the market that was hit first. That could be a really good opportunity to get good staff in to fill the gaps if we can’t fill them internally.”

This idea of a rebalance in the recruitment market also seems to apply to salary expectations, as many are having to take a step down. Kath Knight, human resources director at Mace, is finding salary negotiations a little easier and says the rampant salary inflation that has characterised the job market in recent years has dampened considerably. “People’s expectations aren’t at the same level they might have been,” she says. “They also tend not to be able to play employers off against each other as much as they did before, because there are fewer jobs around.”

Heald mentions one candidate who took a 50% pay cut to get a new position, but was happy just to be working. Smith adds:

“If you talk to people about pay cuts they’re quite realistic about it because they know what the market is like. They’re not going to get the salary they would have two years ago.”

Don’t think of it as a pay cut, it’s more of a readjustment, says Fletcher. “It’s like house prices. Were house prices really at a realistic level before? Or has the fact that they’ve dropped put them at a more realistic level now? I think salaries over the past two years became very inflated because there was such a scarcity of people with the right experience.”

None of this will be of much comfort to the candidates, although there seems to be a sense of confidence among recruiters that things will get better within the next 12 to 14 months. “Regardless of what the economy is doing, senior business professionals will always be needed to drive companies forward and, hopefully, out to other side of the current economic crisis,” says David Cairncross, operations director at Hays Executive.

In many ways, perhaps when the industry does recover, the economic downturn will have had some benefits, leaving a leaner, more competitive recruitment market at an executive level. Although there will be some casualties at the top, it helps to keep things in perspective. As Burnand says: “Let’s not do an article pleading about the desperate state of people like me, because it would be inappropriate. There are hundreds of thousands of people losing their jobs that don’t have the support and the money I’ve got and don’t have the opportunities I’m getting.”

No comments yet