Politicians have been bandying figures around for years – and hugely overpromising. So is mayor Sadiq Khan’s plan to build 65,000 a year anything more than wishful thinking? Joey Gardiner reports on the capital’s intractable housing crisis

London’s Labour mayor, Sadiq Khan, was elected promising to make building more homes his “single biggest priority” in office. His manifesto derided his predecessor’s failure to build 50,000 houses a year, and promised to “break the home-building logjam” and to make 50% of new homes affordable. Since being elected, he has presided over the creation of a hugely ambitious draft London Plan, targeting construction of even more homes - 65,000 a year.

But cold, hard reality is hitting home. The latest government housebuilding figures show Khan’s London is heading backwards – fast. Net additions to the housing stock – which include conversions and changes of use – were down by 20% in London in the year to April, dropping to 31,723. That’s under half the building rate promised in his draft plan. It’s also virtually the same number built in predecessor Boris Johnson’s final year in office.

“We’re talking about more than doubling London’s housing output, so it’s difficult to envisage many boroughs doing anything other than failing the test”

Matthew Spry, Lichfields

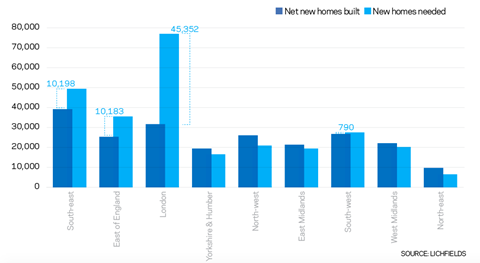

All this happened while housebuilding in much of the rest of the country continued to rise steadily (see graph, below). Increasingly, the figures show, England’s much-discussed housebuilding crisis is in fact simply a failure to build enough homes in the capital. According to the government’s recently introduced standard method for assessing housing need, the country needs to build 196,000 homes each year outside the capital. Last year it provided 190,472, with all Northern and Midlands regions exceeding their quotas. Not hitting the target – but well within spitting distance.

But in the capital, the gap is now a yawning chasm. The standard method recommends 77,000 homes a year – two-and-a-half times real-world delivery. Many are now asking whether there is any chance of closing this chasm without a fundamental rethink that involves some big political sacrifices.

The draft London Plan

Published last December, the draft London Plan highlights a need for 66,000 homes a year in the capital, and proposes abolishing existing density limits to increase the number of homes delivered. It says there is capacity in the capital to deliver 65,000 homes, primarily in identified “opportunity areas” and sets out an ambition for half of all homes to be affordable. The plan is set to face public examination from January 2019.

Also read: Letwin review - more homes, or more red tape?

Also read: Into the unknown - a housebuilding journey

Brexit effect

A large part of London’s current building problem is clearly down to the market, which has been buffeted by stamp duty reform and – of course – Brexit. Stamp duty has hit the market for homes above the £600,000 Help to Buy threshold particularly hard – these sales are a key driver of viability for new-build central London schemes in areas like Nine Elms.

With nearly 20% wiped off the value of “prime” central London property in the last four years, according to Savills, signs of the wider weakening market abound. Housebuilder Berkeley – legendarily adept at reading the market – has shifted its focus outside London after more than a decade of working only in the capital. Listed housebuilder Crest Nicholson last year closed its London office, and in October it said sales on London sites had “slowed significantly” causing “downward pressure” on prices. Khan can fairly claim to have been unlucky in his timing.

Anthony Lee, head of development consultancy at BNP Paribas Real Estate, says the market is particularly challenged in areas where prices are highest. “Developers are struggling to sell as overseas investors, looking at Brexit, are sitting on the fence,” he says. Likewise, Peabody chair Sir Bob Kerslake complains of a “Brexit effect”. Numbers are likely to get worse, too, with just 19,000 housing starts last year, well below the 23,890 completions recorded (albeit these numbers don’t include conversions and change of use contained in the “net additions” figures above).

But beyond the market, there are also significant fears about where Khan is taking policy. Some say the introduction of a requirement for schemes to provide 35% affordable housing or else face lengthy review processes, are making developments unviable. BNP Paribas’ Lee says: “Developers are agreeing to these affordable housing levels just to get a consent – and then finding they can’t deliver.”

Others say the draft London Plan, though not yet formally in effect, is already holding things up. Dan Osborne, London planning director at consultant Barton Willmore, says councils are struggling to work out how to put the new policies around affordable housing into practice. “The London Plan has put the cat amongst the pigeons. It’s very prescriptive and councils are taking a while to digest it. It seems like everything I’m working on is stalled in planning.”

But there are also many supporters of Khan, who has won plaudits for cutting long-term deals with housing associations, supporting genuine social housing and the nascent build-to-rent sector, and accepting the need for ramping up development density.

Peabody’s Kerslake says: “Largely the mayor is doing the right things; he’s recognised the ability of housing associations to cross-subsidise homes for sale is reduced, and has put money into social housing.” Even Berkeley Group chair Tony Pidgley says: “I don’t really blame the mayor – there’s not a lot more he can do,” citing central-government-set stamp duty rates as the main policy blockage to more homes.

And in one sense, the fact of the building shortfall being so concentrated in the capital could be seen as a cause for optimism: solve the problem in London, and you go a long way to solving the problem for England as a whole.

A spokesperson for the mayor of London said the fall-off in build rates was a symptom of developers having “become addicted to soaring house prices,” and questioned the value of simply building “more luxury flats”. The spokesperson said: “We are now seeing the comedown, compounded by the government’s chaotic mishandling of Brexit. These figures confirm why Sadiq [Khan] has the right approach by focusing on building new council, social rented, and other genuinely affordable homes.”

Net additions versus need

This month the government published net additions figures which showed 222,000 homes were built in England in the year to April 2018. This contrasts with the identified need of 273,000 homes, by the government’s “standard method” of assessment.

London, the South-east, the East and South-west regions failed to hit their targets, while all Northern and Midlands regions exceeded the assessed need level. While the South-west was just 3% below assessed need, the East and South-east missed their targets by 21% and 29% respectively.

In London, however, net additions were an order of magnitude smaller than the target, at just 31,727 versus assessed “need” of 77,000 new homes.

Impossible

But if Khan has made progress on affordable housing, the reality is that on build numbers overall, his task is nigh on impossible. Even the previous version of the London Plan put through during Boris Johnson’s tenure, targeting construction of just 42,000 homes a year, was described as undeliverable by its official inspector. It was only approved because the inspector said the old 32,010 target fell so “woefully short”.

The reality is that London housing completions have never hit even 40,000 a year since the Second World War, according to the GLA, let alone 65,000. Consultant Stephen Hill, director at C20 Futureplanners, says: “With London you always come back to the big gap in perception of the scale of the problem. We’ve never done these numbers we’re talking about. There’s a mismatch between expectations and the means of delivery.”

Yet Khan’s 65,000 homes-a-year draft plan rules out looking to the green belt to find space for these homes. It justifies the number by talking up development density and assuming a far greater build rate, on small sites in particular, than has ever previously been achieved. Ian Gordon, emeritus professor of human geography at the London School of Economics (LSE), says it assumes build rates will increase five-fold. “There’s no real evidence to support this; it’s just a finger in the air,” he says, something the LSE’s official response to the consultation on the plan describes as “wholly incredible”. Matthew Spry, senior director at planning consultant Lichfields, agrees the plan relies on “heroic assumptions” of what is possible.

Pressure cooker

But given the government’s introduction this month of its “housing delivery test”, which penalises local authorities that don’t hit their housing targets, the consequences of over-ambitious targets for London boroughs are suddenly quite grave. Lichfields’ Spry estimates that by 2020, four out of five boroughs will fail the test, making their plans officially out of date, and thereby opening them up to speculative development under the “presumption in favour” contained in national planning policy. “London authorities have a really big challenge down the line,” Spry says. “It’s like a pressure cooker, something has to give.

“We’re talking about more than doubling London’s housing output, so it’s difficult to envisage many boroughs doing anything other than failing the test.”

While this may have some benefits for developers, the broader impact could still be negative if boroughs consider there’s just no point spending the effort in drawing up a local plan. Richard Crawley, programme manager at the Planning Advisory Service, says: “It potentially brings planning and plan-making into disrepute. Why should a borough put energy into the local plan process if they don’t get any benefit from it?”

Many planners have a two-word answer to all these woes: green belt. Under pressure from rival Zac Goldsmith in the mayoral election, Sadiq Khan pledged to strengthen protection for green belt land surrounding the capital, much of which is contained in London boroughs, and he has stuck to his word. But critics say much of this totemic land is in reality of low environmental quality, and would be much better used meeting the need for homes. Berkeley Group’s Pidgley says: “There should be a proper review of it. Where it’s proven to be beneficial as green belt, fine. But in special circumstances housing should take priority.”

Organisations as diverse as the left-leaning IPPR think tank and free-market Adam Smith Institute have also in recent years come to the conclusion that a strategic review of green belt is needed. Kerslake, who chaired a London Housing Commission for the IPPR, says: “We argued green belt should be looked at. Of course it’s a political challenge, but it should be on the table. Even a fairly modest adjustment would give significant boost to supply.”

Even more fundamental, perhaps, would be an acceptance that London itself is never going to meet all its housing need. Khan’s draft plan talks about co-operation with surrounding councils, but nevertheless states that it “aims to accommodate all of London’s growth within its boundaries”.

But Lichfields’ Spry says there is another way: “A much more realistic strategy would be to try and deliver in London a number in the mid-40s, then say ‘there is 20,000-30,000 homes a year of unmet need, and this is how we deal with this in the wider South-east’.”

Beggar my neighbour

Khan can’t force neighbouring districts to build more, but they do have a duty to co-operate where he can prove London’s need can’t be met. Indeed, this solution is exactly that proposed by the London Plan inspector in 2014 – but Khan hasn’t gone down this road. Kerslake’s Housing Commission recommended beefed-up powers to force co-operation on this precise point, but in the absence of that the LSE’s Gordon says discussions with neighbouring authorities have hit a brick wall. “My sense,” he says, “is the surrounding authorities are asking Khan to make the same sacrifices as they are – in terms of green belt – if they are to be persuaded to take more homes. A substantial obstacle is the lack of a gesture in terms of moving on green belt.”

C20 Futureplanners’ Hill says a national strategy is needed to address these cross-boundary issues. “The absence of a national plan is a real weakness.”

In all of this, of course, the principal effect is felt by Londoners, who have to endure sky-high rents and house prices on average 12 times income. With the housing delivery test, London boroughs themselves are now under threat too, while housing secretary James Brokenshire’s recent letter to Khan savaging his plan suggests the mayor is unlikely to get much help from that source. Given the numbers, solving London’s housing problem now has a national significance that implies more radical action is required.

No comments yet