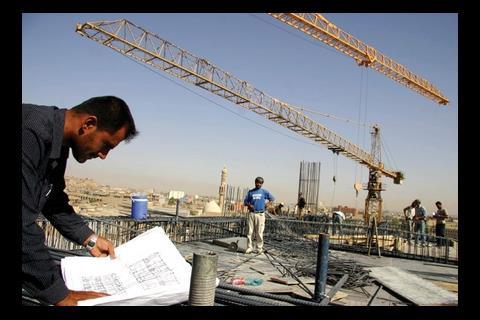

Emily Wright reports on nation-building in the world's most dangerous country

‘You never know what will happen next in Iraq,” says a project director working for a large Iraqi construction company in Mosul, the second biggest city in the country. He didn’t want us to print his name for security reasons, but he was one of the few British workers in the country through the worst of the post-occupation between 2005 and 2007. “One evening in Basra I was having a drink with a friend when a rocket slammed into the living area of the camp. Once we’d picked ourselves up, we ran around to see where it had exploded and found it was right on top of my colleague’s trailer. It totally destroyed it, along with everything inside. Thank goodness he was out with me at the time.”

Dramatic though it sounds, such dangers used to be everyday hazards in Iraq: “I’ve worked under constant mortar and rocket attacks. We only stopped to use the shelters when the alarms went off.

You couldn’t go outside the perimeter unless you had personal armed guards in armoured vehicles to protect you.”

The security situation has improved since then – the site in Mosul only gets occasional small arms fire – but Iraq is still a contender for most dangerous country in the world. The project manager says: “If an alarm sounds when you’re driving, you’re expected to get out of the car and lie face down at the side of the road until the all clear is sounded. It’s unbelievable. The locals I’ve met are lovely and friendly, but even they are afraid to walk around the towns and cities – they know they’re liable to be blown up at any time.”

Set against that is the lure of reconstruction work – and the knowledge that it’s the early bird that wins the infrastructure contract. As tendering starts for schemes such as the $3bn (£1.8bn) Baghdad metro (announced earlier this month), it is likely that more British construction firms will be itching to get in on the action. But how can companies be sure not to miss out on the opportunities while minimising dangers to their staff? Here Building outlines where the work is, how to get it and how to protect employees from the omnipresent security risks.

What’s on offer for companies

There has been little effective investment in Iraq’s infrastructure for the past 20 years. Little surprise, then, that the rebuilding project is of gigantic proportions. “Iraq is short on just about everything,” says Michael Thomas, director general of the Middle East Association, a body that focuses on developing trade relations between the UK and the Middle East.

“They don’t just need people out there helping rebuild infrastructure systems and buildings, they need suppliers, too – everything from heavy machinery to materials. It is one of the most opportunity-rich countries for the UK construction industry right now.”

The main source of work for construction firms is the $70bn (£43bn) infrastructure reconstruction programme announced by the Iraqi government earlier this year. The country’s most urgent need is for a functioning electrical system, so much of this money will go on power and cable projects. One scheme, funded by the UK, US and Swiss governments, is for 24 power stations: Iraq has signed multibillion dollar deals with two energy companies, Siemens and GE, to have these onstream by 2012. Work is expected to start early next year on three of the stations, but it is understood that the rest are still tendering. In fact, the Iraqi Ministry of Electricity is hosting a conference next week in Kurdistan for international power companies to discuss construction and engineering for plants.

Iraq’s housing is also in desperate need of renewal. The state is to spend $25bn (£15bn) of the infrastructure package on building 3.5 million homes over the next 10 years. This should account for 15% of the country’s housing needs. The other 85% will be funded by private sector investors.

In addition to the infrastructure spending, most of Iraq’s cities are in need of renewal. Cyril Sweett has already attended talks about taking a role on a £30bn project to rebuild Baghdad, Najaf and Karbala. The firm, along with a number of other construction companies, met the regional directors of the cities in May.

The Baghdad masterplan is understood to include two megaprojects. The first, called the Future City, involves rebuilding the old city. The second, called 10 x 10, will be a $10bn (£6.1bn) extension to the south. It will be built over 10 years and will house 2 million people. There will also be two huge projects in Karbala: the redevelopment of the city itself and the construction of New Karbala, a 30km2 city worth $20bn (£12bn). It is understood that US architect Burt Hill has been appointed to deliver the masterplan.

Exactly how many jobs these schemes will create is not known, but Nazar Mohammed, one of the directors working in Cyril Sweett’s Iraq office, says that New Karbala alone “is expected to create 80,000”.

What’s on offer for workers

There are huge financial rewards for individuals willing to risk working in Iraq. According to recruitment firm Zoiren International, ads for roles such as site managers and project directors receive more than 3,000 applicants, more than double the number this time last year. This is, in part, down to the recession in the UK and the UAE, but it also has a lot to do with the lure of the salaries on offer.

I haven’t spoken to a single candidate wanting to work in Iraq to better the country or do their bit. It’s too dangerous to be philanthropic

Neil Morris, Digby Morris

“I haven’t spoken to a single candidate wanting to work in Iraq to better the country or do their bit. It’s too dangerous to be philanthropic,” says Neil Morris, director of Middle East recruitment specialist Digby Morris. “They do it entirely for the money. You can be out there earning £200,000 a year. I know people who have gone out two or three times now for this very reason. They usually only stop going when their wives put their foot down.”

Funding and investment

Many countries have promised to help fund the rebuilding of Iraq’s infrastructure, and so far 17 have deposited $494m (£300m) in the World Bank’s Iraq trust fund. There should be more to come: the Madrid Conference on Reconstruction in October 2003 gathered $33bn (£20bn) in pledges from the global community.

That may sound like a lot of money, but it is a pretty small beer compared with what is needed. The World Bank’s assessment of Iraq’s construction needs shows that $188bn (£115bn) would be required overall by the end of 2010. National donations only cover 48% of this. Additional funds must be provided through private funding from international investors and through PFI and PPP schemes. This side of the investment is picking up slowly as security in Iraq stabilises, but investors are nervous and are keeping plans close to their chest. The Trade Bank of Iraq is one source of funding. Set up by the US authorities in 2003 to finance trade and reconstruction projects, it has total assets of $10bn (£6.1bn) to go towards private funding initiatives. Fairfax, a London-based fund, is planning to invest up to $200m (£122m) this year, but most private investment in Iraq comes from the Gulf, Turkey and Iran or expatriate Iraqis looking to gain a business foothold in the country.

According to Ahmed Ridha, chairman of Iraq’s National Investment Commission, proposals for private investment include a $13bn (£8bn) port for the city of Basra. The biggest projects, including the reconstruction of the three cities mentioned above, are being backed by an Abu Dhabi-based investor called National Holding. Another, the Emirates International Investment Company, is also planning a multi-million pound investment in a residential scheme.

Getting involved

After a trade mission led by business secretary Peter Mandelson to Iraq in April, the Middle East Association is planning another at the end of the year. It is keen to involve as many construction firms as possible in this one. The mission will be with the Iraq Britain Business Council and will include meetings with ministers. Thomas says: “The UK needs to get involved before the French and Italians get in first.”

He adds that, despite the obvious tensions between the Iraqis and the British, most Iraqi ministers have respect for UK firms and are keen for them to come over to help with the rebuilding: “Many Iraqis were educated in the UK,” he says. “A lot went to UK schools or universities, so there is common ground. Iraqi firms are ready to set up joint ventures and forge strong business and trade links.”

The risks

The war may be substantially over in Iraq, but the government is not in full control of the country, and violence is a constant threat. Unfortunately, construction sites have a political significance, and are still targets for mortar attack. Between March 2003 and July 2009, 1,395 workers died on American-funded projects and it is estimated that 25% of reconstruction funds have had to be used to provide security for construction workers. Graham Hand, chief executive of British Expertise, which advises British companies working abroad, says vandalism is something to watch out for: “Attacks are politically charged as some Iraqis will deliberately attempt to damage products and machinery to impair the progress made to improve the country.”

Economic crime is also common. Transparency International, an NGO that assesses levels of corruption around the world estimates that Iraq is the third worst country, after Somalia and Burma.

Then there is the question of kidnapping. More than 11% of professionals who responded to the Chartered Institute of Building’s crime in construction survey in June said their firm had been affected. Matthew Hunt, intelligence associate at The Risk Advisory Group, has this advice: “Anyone who looks obviously western is at greater risk. We advise anyone in Iraq to have an armed escort at all times.”

Richard Kingston, Middle East director at Cyril Sweett advises hiring a reputable Iraqi security firm as an escort rather than US or UK companies whose blacked-out Land Rovers attract even more attention. He also advises the hiring of Iraqi staff and even renaming UK firms to sounds less western, which is something Cyril Sweett discussed. “We just weren’t sure what the reaction from locals would be to a UK-branded site in the middle of their country full of workers with UK-branded hard hats and jackets,” he says. “We thought about keeping the logo and coming up with a more Arabic-sounding name.” In the end it decided it could get away with the British name if it hired a fully Iraqi workforce.

Living arrangements can also be tough. Senior workers are usually put up in hotels but if you are a site manager, for example, you could well find yourself living in a large tent with your fellow workers, advises Morris: “If you are thinking of working in Iraq, I would say: don’t do it. Well, not if you haven’t thought it through properly. It’s pretty hardcore and you may well find yourself having to duck under a nearby table during a sudden mortar attack.”

A guide to working in Iraq

Security

Nick Fishlock, director of specialist recruitment agency, Zoiren International says: “You will be issued with body armour. It’s basically a waistcoat with four Kevlar plates – the synthetic fibre used in Formula One cars.”

Routes need to be changed regularly to avoid anyone noticing your pattern of travel. This can be time-consuming and unnerving. British nationals should take particular care if they are working on US-funded projects, which have become the most highly targeted sites for vandalism and bombing.

The precariousness of working in Iraq means life insurance can be exorbitant. Other problems include having time limits on site visits. This is for security reasons as anyone obviously related to reconstruction work should avoid being exposed and away from the safety of armoured vehicles for too long at a time.

Communications

Be prepared for an extremely basic communications set-up. Landlines and mobile are unreliable and internet connections intermittent. “Phone lines are terrible,” says Richard Kingston, Middle East director at Cyril Sweett. “We have had to wait to communicate with our Iraq office until after midnight when the lines are freed up. We have been offered a large mast on top of the office building to improve this situation by the Iraqi government but I’m not sure that wouldn’t make us an instant target.” Getting about by road and rail is also difficult, with many routes in disrepair.

Getting there

“Getting to Iraq is not like going to BA and booking a flight,” says Neil Morris of Middle East and Eastern Europe recruitment company, Digby Morris. “Usually flights are private charters organised by companies from Qatar or Dubai.” Things are looking easier now as Gulf Air announced at the beginning of the month that it would soon be flying from other Middle East airports to five destinations in Iraq, adding Basra and Solamnia to the previously announced routes to Baghdad, Najaf and Erbil. A visa needs to be obtained from the Iraqi embassy or consulate before leaving the UK.

Tax

In 2004, the Coalition Provisional Authority introduced a flat tax of 15% on all income earned by Iraqi and foreign companies. Income derived from foreign government sources and international organisations are not taxable.

Dealing with ministries

Any major projects or tenders will need to go to ministries. All brochures and letters must be in both English and Arabic. In meetings it is advisable to use a translator. Iraq ministries will often only provide tender documents to companies that can provide a letter of authority from either a chamber of commerce or an Iraqi embassy.

Companies should find out whether this applies to the particular ministry they are dealing with. To certify these documents, they must be sent to the Arab British Chambers of Commerce, then to the Foreign Office’s Legislation Office and finally to the Iraqi embassy. Good relationships and trust are a must before contracts can be written up and it is strongly advised that an Iraqi lawyer is present or consulted when reviewing any commercial agency agreements.

Local representation and branch offices

Foreign companies are free to open branch offices but are required to register their office number with the Ministry of Trade and get a business ID number. No sponsorship is needed to open a branch office.

Money

Credit cards are not widely used and there are few ATMs. Travellers are advised to carry cash.

Useful contacts

The Arab British Chambers of Commerce

020-7235 4363

www.abcc.org.uk

The Iraq embassy

020-7590 0220

www.iraqembassy.org.uk

British Expertise

020-7824 1920

www.britishexpertise.org

Middle East Association

020-7839 2137

www.the-mea.co.uk

Iraqi Ministry of Foreign Affairs

www.iraqmofa.net

Foreign Office

020-7008 1500

www.fco.gov.uk

Postscript

Additional reporting by Anna Reynolds and Sophie Griffiths

No comments yet