Imagine getting all the materials for a four-bedroom house with nanny flat through a standard-sized doorway on a busy London street (yes, that one on the left). Tricky, no? Now imagine doing it against the wishes of some mightily cheesed off and powerful neighbours. Thomas Lane reports on a project that was more keyhole surgery than construction

If there was an award for Britain’s craziest project, this west London house would be at the top of the shortlist. It’s a four-bedroom home with a nanny flat, generously proportioned living space and three patios – so far, so estate agent’s blurb. But all are shoehorned into a garden behind a house in upmarket Gloucester Road.

The house’s wealthy and powerful neighbours were determined that nothing was going to be built on the 460m2 site but, after two planning applications and two appeals, permission was finally wrung out of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Just to give you an idea of how many people were involved, 20 party-wall agreements were needed before work could start.

Obtaining planning permission was only the first hurdle, however. Because the house is in a garden behind a terrace of shops with flats above, the only way in was through the communal hallway of the property fronting Gloucester Road – which was divided into flats and occupied by some of the residents bitterly opposed to the whole project.

Assuming the builders could get past the angry neighbours, the only way into the garden was through a standard-sized doorway. And this house is no lightweight; it has a substantial basement, heavily reinforced concrete retaining walls and slab plus a steel frame. Not the sort of materials that can be easily carried through a doorway.

Predictably, the neighbours weren’t going to take their planning defeat lying down. They put all their energies into making life as difficult as possible for the contractor. Yet despite these multiple obstacles, the multimillion house is due to be finished any day now. How has the project team managed to deliver this seemingly impossible scheme? And more to the point, do you have to be mad to take on a project like this?

In fact the client, developer Ivo Hesmondhalgh, comes across as perfectly calm and sane. When he first saw the site, it was occupied by a large, derelict shed so getting planning permission to build what he intended to be his dream home wasn’t totally beyond the bounds of possibility. “I really like architecture and wanted a modern house,” he says. “I wasn’t confident because it was so complicated but I knew I had the right people to help me and the rewards for doing it outweighed the problems. I also knew it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

In 2001 Hesmondhalgh took a massive gamble by buying the plot without residential planning permission. He then set about finding an architect and getting permission for a change of use from business to residential. He got that “relatively easily” in 2002. He then held a private design competition, which was won by Studio Bednarski.

This is where the problems began. The Studio Bednarski proposal was no bigger than the existing building except for the addition of a basement to increase the internal volume of the home. “The new building was entirely in the envelope of the old building and would be better to look at than the junk that was already there,” says Cezary Bednarski, the practice’s founder.

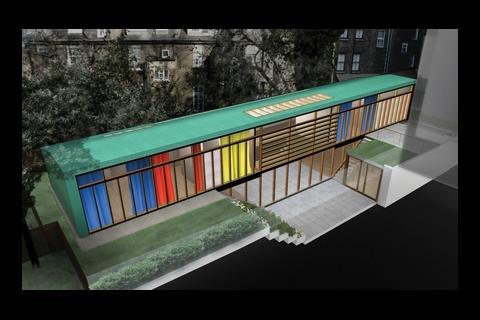

He says he conceived the design as a lightweight object to lessen its impact. “We had to be clever so we created a Japanese-type garden pavilion, not a house, which is a heavy, defensive object,” he says.

There was another important aspect to Bednarski’s design: “The whole building was conceived so it could be built through that passageway.” Unfortunately, the neighbours weren’t impressed. “We had neighbours who were very powerful including, I believe, the top commercial lawyer in the UK,” says Bednarski. “They decided they would not have it. The council was aware of their opinions and was very wary of giving in.”

Indeed the council refused the first application, saying the design was inappropriate for its location. Hesmondhalgh appealed, but lost on the grounds that trees in the neighbouring Launceston place would be damaged. Bednarski was delighted, however, because the appeal inspector was complimentary about his design. “We thought this was brilliant as all we had to do was prove the trees wouldn’t be affected,” he says.

But Kensington and Chelsea planners took no notice of the inspector’s comments and refused the second application on design grounds again. Hesmondhalgh appealed this second decision and, this time, in March 2004, he won. The planning process had taken nearly two-and-a-half years.

Meanwhile Hesmondhalgh asked the contractor, Diamond Construction (2000), a firm he has worked with for the past 20 years, to do some initial investigations of the site. According to Sam Samra, the firm’s director, the limited access through the hallway meant things got off to a bad start. “We started getting complaints from the neighbours. The lads made a mess of the carpet just doing the initial works,” he says.

In fact, Samra reckons the contractor couldn’t have done the job without an unexpected stroke of luck. In the wake of the muddy carpet incident, a meeting with the residents of the building on Gloucester Road about conditions for access didn’t go well. “There were a lot of conditions being set for that passage,” says Samra. “There was no way we could have done it. There would have been a lot of complaints and we would have ended up abandoning the job.”

But the project team got a lucky break in the form of an empty post office. It is located in Victoria Grove, which is perpendicular to Gloucester Road, and backs on to the side of the site. By chance, Hesmondhalgh heard from an estate agent he knew that it was being vacated and did a deal to take it over for a year-and-a-half. This meant access was much easier as the team had a front door to the street free from irate neighbours. “It was a relief for everyone,” says Samra.

In August 2005 Diamond could finally start work. The post office had saved the job or, at any rate, had taken it from virtually impossible to extremely challenging. “We took out half the shopfront and the back wall of the shop,” says Samra. “Then, when we got this sorted out, we had more problems as the council’s highways department wouldn’t let us leave anything in the road because it was too narrow.”

The council wouldn’t allow a skip but gave permission for a lorry to be parked in the road for an hour at a time. Waste from the excavation would be carried from the site into the shop and stored at the front ready for collection. A lorry equipped with a grab bucket was used to remove the waste – 126 lorry loads of spoil were dispatched this way. The team could only unload and load in the mornings – a decision made to placate a flower shop owner across the road whose initial reaction to the arrival of the lorries was: “Allah will kill you.”

“I went across to explain what we were doing and we weren’t deliberately trying to cause problems,” says Samra. “She said, ‘I open my shop at 1pm’, so we said we would only have deliveries before 1pm.”

Creating the basement was one of the most demanding parts of the job. Diamond could only get a mini-excavator into the site and a small dumper truck to move material from the workface to the back of the shop. They had to dig out a 4m deep hole to create the basement and ensure none of the 13 neighbouring properties fell into it. Four properties on Victoria Grove had to be underpinned as the excavation was up to 3m below their foundations. The work was agonisingly slow, and took a month in all. “We had to be really careful with the digger and do quite a lot of it by hand,” says Samra. A retaining wall was built around the perimeter of the rest of the site.

By now, the neighbours’ complaints had started to focus on noise. Water started pouring into the excavated basement, “like a stream”, according to contracts manager Raj Kaler. This called for a dewatering pump, which was meant to be switched off at night. Inevitably someone forgot to turn it off. “This woman rang me in the middle of the night saying she could hear a noise which was the water pump,” says Kaler. “I said I was really sorry and it wouldn’t happen again. I gave her a box of chocolates and she was okay after that.”

Diamond even fitted secondary glazing to the windows of a relocation specialist, whose office was closest to the site. “We helped in any way we could, to show our respect to the neighbourhood,” says Samra.

Once the retaining wall had been built and mini-piles had been sunk, work moved on to constructing the foundation slab. This consisted of ground beams spanning between the mini-piles, topped by the slab. The floor beams were 600mm2 in section and the floor slab sitting on top was 300mm thick, which equals lots of concrete.

The access problems meant concrete had to be mixed onsite. The cement arrived in small bags – 720 on each load – which were dropped on to the pavement and carried through to the back of the shop. Concrete was mixed in a domestic-sized mixer and placed as needed. The main slab was cast in sections with each section placed in one day.

Up to 25 people were needed to mix and place the concrete. “We had to pull everyone off other jobs so we could do the sections in one go. It was about 85% labour,” says Paul Samra, Sam’s brother and the construction manager on the site. “I was mixing concrete in my sleep,” laughs Kaler.

As work progressed on the slab towards the west side of the site, steel erection could begin on the completed east end. “The steel was pretty straightforward except we only had hoists or, in many cases, sheer manpower,” says Paul Samra.

But reaching this stage of the project meant the final size of the building was revealed. More complaints started rolling in to the council planning department. “Every time the planning enforcement officer came down, it was fine,” says Paul Samra. “The overall height was spot on and it was 15mm wider than the drawings, which the planning officer wasn’t bothered about. I had kept double-checking as I went along.”

With the steel completed, work could move on to the internal stud walling and the roof. Unfortunately, at this point – November 2006 – the weather changed. “While we were doing the steel, it was glorious sunny weather,” says Paul Samra. “As soon as we started on the timber, the heavens opened.”

The bad weather has delayed the project but fortunately the post office owner has agreed to extend the lease. Drilling holes in the steel for timber connections proved hugely time-consuming. It took eight people three months to do the timber works.

The roof and north side of the building have been clad in copper, and a hardwood-framed glazed wall has been inserted on the south side to get as much light as possible into the building. Initially, the glazed areas were supplied as complete units but Diamond quickly switched to building these insitu as the units were too heavy to manhandle.

The hard work is over and decorating is due to start soon, with Hesmondhalgh moving in towards the end of summer. Let’s just hope he gets on with his neighbours.

Was it all worth it?

Entry to the house is via an unassuming door next to an estate agent on Gloucester Road. At the end of the communal passageway is a door, which is the entrance to the new property. Going through it is probably the nearest you will get to experiencing what it must be like to enter Narnia though a wardrobe.

Bednarski has created a generous entrance lobby beyond the door to give visitors a sense of arrival. The lobby opens on to a huge corridor running the length of the home. The bedrooms are all situated to the left of this and all have access to a patio at this level.

Bednarski has broken up this strongly linear arrangement by creating a double-height space in the middle of the home. The corridor takes the form of a bridge with glass sides over this space. Light streams in through the floor-to-ceiling glazing.

Downstairs is a vast living area with a kitchen under one of the patios. The double-height space and kitchen open out on to a patio at basement level, which gives it added privacy as it cannot be overlooked from the adjacent buildings.

Project team

Client Ivo Hesmondhalgh

Architect Studio Bednarski

Project manager Stuart & Duffy

Surveyor Baron Property Consultancy

Contractor Diamond Construction (2000)

Party wall surveyor Cook Steed Associates

Structural engineer Techniker M&E

Engineer MEC Bird Associates

Downloads

Plan view

Other, Size 0 kb

1 Readers' comment