Studio E took two 120-year-old plane trees as the starting point for its west London primary school – and as the inspiration for a whole toy cupboard of sustainable features. The upshot is that these could be the first kids ever to love their greens.

Two trees were all that would remain once the Sacred Heart Primary School was demolished to make way for a larger school building. But what magnificent trees they were! Thirty metres high and 120 years old, these two London planes were topped by huge globes of greenery. Their location, near the sclerotic arteries of Hammersmith town centre in west London, made them even more precious.

So when Studio E Architects came to design the replacement building, for the merged Larmenier & Sacred Heart primary school, it was a no-brainer: it would have to be built around the trees. The trouble was, as director Andrzej Kuszell points out, “When we analysed the site and its access and orientation, we found that the trees and the building wanted to be in the same space.”

Studio E came up with the obvious solution. They designed the school as a two-storey crescent threaded between the two trees and partly wrapped around one of them. But it didn’t stop there. The building’s celebration of the two trees has been expanded into a comprehensive package of sustainable features, and these double as handy aids in teaching the school’s 450 pupils about the environment. And the pupils aren’t the only people to have come along to learn about sustainable design: in June, Tony Blair and California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger came to the school to have a look at its mix of eco design and education.

A variety of plants and the ample use of untreated timber are the most self-evidently green features of the building. A carpet of low-maintenance sedum plants has been laid across the roof pitch on the inner, concave side of the crescent, where it is highly visible from the playground. Across the outer, south-facing facade, creepers are slowly spreading along wires to give sun shading. Beyond that, shrubs form discrete boundaries between play areas for different age groups. The outer facade is faced in untreated larch boarding, while the exposed roof beams inside are made of Kerto laminated timber, cut to size at Finnforest’s plant in Germany.

The overall configuration of the building is more complex, though still largely based on natural forms. In plan, the ground floor adopts the conventional arrangement of rooms opening off either side of a central corridor, although the upper floor is only one-sided.

But the architect has responded to the curved form and the need for a range of room sizes by devising a different geometry for either side of the building. All the regular classrooms have been strung out over two floors on the outer, south-facing side of the crescent. These have been arranged according to a simple radial geometry centred on the tree, with the partitions as the spokes.

All the other spaces have been contained within a single storey on the inner side of the crescent. From the tiny staff offices and reception desk sited next to the main entrance, this side fans out gradually in depth and height to the large library, music and art rooms at the other end. The natural twist added here, figuratively and literally, was to apply the spiralling geometry of the sea shell, which is based on the golden section and the Fibonacci sequence 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21 and so on. It’s a lovely idea that works in terms of the orderly layout of diverse spaces and the embedded lesson of nature’s mathematical principles it offers to pupils, although it has to be said that the latter is far from obvious in the finished building.

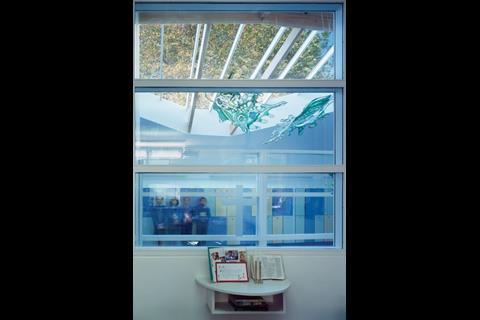

The most ingenious aspect of the building, however, is the highly complex, interactive system for channelling daylight, natural ventilation and views into both floors of classrooms on the outer side of the crescent. The basic elements here are small segment-shaped lightwells that drop down between the central corridor and pairs of classrooms on both floors. On the upper floor, each lightwell is open to the corridor, while on the ground floor it is partly shielded by a head-height screen which means it can serve as small teaching space that supplements the regular classrooms it adjoins. Each lightwell is capped by a skylight and bounded by glazed partitions to the adjoining classrooms, so that it funnels daylight into the classrooms on both floors. It also works in the opposite way by offering views up to the sky and the central tree’s upper branches.

When we analysed the site and its access and orientation, we found that the trees and the building wanted to be in

the same spaceAndrzej Kuszell, director, Studio E Architects

Rising up alongside the skylights are clerestory windows, and these open to ventilate the upper classrooms in combination with opening windows along the external wall. The downstairs classrooms are similarly ventilated through vertical ducts discharging through adjoining, and acoustically separated, clerestory windows. Even the central corridor and its ancillary teaching spaces are ventilated by a third set of clerestorey windows, in this case with the fresh air supplied through underground ducts from the enigmatic little pyramids that pop up among the playground shrubbery.

Other sustainable features include photovoltaic panels on the roof that generate 10% of the school’s power. In addition, a structural frame of insitu reinforced concrete and partitions of heavy concrete blockwork contribute to a thermal mass that reduces temperature swings in hot and cold weather by up to 3°C. It was built for the economical sum of £5.2m, or £1,995/m2.

The pupils themselves have joined in the nature-inspired building process with great enthusiasm and creativity. With the help of a freelance artist and the school’s art teacher, they designed leaf patterns that were imprinted on window awnings and mobile sculptures that hang within the corridor lightwells. Kuszell stresses that engaging the children in the development process would not have come about without extensive consultations between pupils, parents, teachers and designers. This went as far as 12 site visits during construction, as well as umpteen school exercises in science, art, drama and writing poems.

As well as the many green features and their educational potential, it is the transparency and openness of the building that particularly pleases the headteacher, Sister Hannah Maria Dwyer. She points to the open dogleg staircase at the centre of the building and to the upper corridor where you can look across each lightwell into four classrooms simultaneously. “The infants on the ground floor and the junior children on the first floor can see each other throughout the day,” she says. “That’s a huge factor in the new school, which is an amalgamation of an infant and a junior school.”

“The staff appreciate the daylight and ventilation and all the amenities being grouped together at the centre,” she continues. “So we don’t have children all going in different directions.”

The abundance of large, low-silled windows around and through the school dissolves the boundaries between spaces and binds the building into the surrounding landscape. Connectivity between inside and outside is reinforced in the ground floor plan, where the infants’ toilets take the form of perimeter extensions that are equally accessible from both classrooms and playground.

As Dwyer explains, the children take great interest and pride in their green school, and in the two magnificent trees that inspired it.

One of her pupils, Isabella Snape, finds the classrooms to be “great places for learning, as they all contain a perfect amount of space”. The large windows “create a very peaceful atmosphere as well as giving a lovely view of the playground”. As for the green roof and solar panels, she finds these very important “as we all have to do our bit to help the world”. For one building to be inspirational on so many levels, this 10-year-old says it all.

Downloads

Section showing ventilation of upper classrooms

Other, Size 0 kbSection showing ventilation of central corridor

Other, Size 0 kbGround-floor plan

Other, Size 0 kb

No comments yet