Despite warnings that the Palace of Westminster was at growing risk of a catastrophe, little was done to begin work on its urgently needed refurbishment. Then on 15 April Notre-Dame de Paris came within minutes of being burnt to the ground. Jonathan Owen reports on a project that is finally getting the attention it deserves

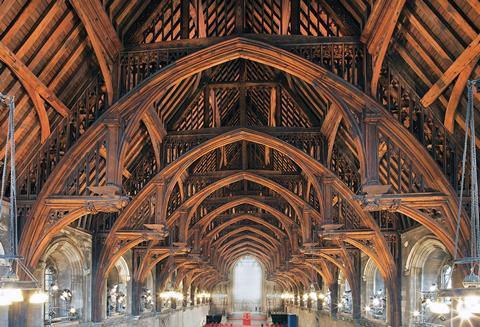

If you’re aghast at the state of politics in this country, you should take a look at the Palace of Westminster. It’s literally falling to bits. Riddled with asbestos, with crumbling masonry, leaking pipes and roofs, dilapidated M&E systems, and neglected for decades in a “make do and mend” approach, if it were any other building it would be facing demolition.

But it is not any other building. The grade I-listed building is the mother of parliaments, not to mention a Unesco World Heritage Site. And no matter what one may think of the machinations of the politicians working inside, it’s clear the building itself is in urgent need of a major overhaul – an urgency made all the more compelling by the Notre-Dame cathedral fire of 15 April.

So what’s being done to rescue the Palace of Westminster from the risk of fire and bring it up to a standard that is fit for its exalted purpose as the seat of democracy? And what are the chances that such a major refurbishment can come in on time and on budget?

If the palace were not a listed building of the highest heritage value, its owners would probably be advised to demolish and rebuild

Pre-Feasibility Study, 2012

An impending crisis

Concerns over the condition of the Palace of Westminster have been being raised for decades, with a series of reports in recent years warning of the growing risk of a catastrophe.

A pre-feasibility study on the condition of the Palace of Westminster, in 2012, warned of a “looming crisis” and “severe hazards that could occur if fundamental renovation is delayed indefinitely.” It stated: “If the palace were not a listed building of the highest heritage value, its owners would probably be advised to demolish and rebuild.”

The maintenance bill for the building shows signs of this – and costs are rising each year the work is delayed. Nearly £74m was spent on essential maintenance work for the palace during 2017/18, compared with £49m in the 2014/15 financial year.

But the urgency of the situation has not been reflected by the pace of political change. A report by the Joint Committee on the Palace of Westminster in 2016 recommended that politicians and peers should vacate Westminster so that the refurb could take place in the face of “an impending crisis”. It warned of the “substantial and growing risk” of “a single, catastrophic event, such as a major fire” and suggested work start by 2023.

In the event, it wasn’t until 2018 that MPs and peers voted in favour of the recommendation, and the government finally put forward the Parliamentary Buildings (Restoration and Renewal) Bill this month. The bill received its second reading this week.

Labour MP Chris Bryant, who was a member of the committee, described the rate of progress as “shockingly slow”. He said: “We have dragged our feet at every turn, in particular because I think Number 10 got the collywobbles about spending money at a time when public services need money as well. But I think Notre-Dame acted as a bit of a wake-up call.”

The government is hoping to replicate the success of the governance model used to deliver the 2012 Olympics, with a sponsor body and a delivery authority.

Assuming the bill is passed this year, the sponsor body will come into being, with a delivery authority expected to be up and running next year, a concept design and an outline business case ready by 2021 and planning applications to be submitted in the early 2020s, according to officials.

And proposals to rebuild Richmond House to serve as a stand-in parliament while Westminster is refurbished are now out for consultation, as part of an ambitious £1.6bn Northern Estate Programme to redevelop a cluster of buildings a stone’s throw from parliament. This marks a major milestone, for the Westminster refurb will not start until the Palace of Westminster has been vacated.

Firms working on the Northern Estate programme include BDP as lead designer, with the programme, project and cost management carried out by WSP and Gleeds, with Wates as main works contracting partner. Mace is project manager for the Richmond House redevelopment, with Lendlease the main contractor on the AHMM-designed building.

Timeline in doubt

Planning applications will be made later this year and officials claim the work will be complete by the mid-2020s, enabling the Westminster refurb to finally begin. But this timeline is already in doubt, with an ongoing dispute over access to land owned by the Ministry of Defence that could see the completion of the work delayed until 2028 (and extra costs of £350m added to the bill, as reported by Building).

In the meantime, the Palace of Westminster remains at risk, with risers in parliament acting as internal chimneys that could increase the likelihood of a fire spreading. The Houses of Parliament restoration and renewal programme warns that “vast quantities of combustible materials” along with the “huge network of ventilation shafts and floor voids” create “ideal conditions for fire and smoke to spread throughout the building”.

The refurb is already several years late, and the cost of the multibillion-pound project remains unknown, but will significantly exceed the £3.9bn figure estimated in a parliament-commissioned report by Aecom, Deloitte and HOK in 2014. The report envisaged work starting by 2020 and completion by 2026 and estimated it would cost £379m to provide MPs and peers with temporary homes during the refurb.

This is a fraction of the £1.6bn set to be spent on the Northern Estate programme, which is centred on converting Richmond House into a temporary home for MPs.

The costs of converting the Queen Elizabeth II conference centre in Westminster to accommodate peers are unknown, but planning applications for this work are expected to be made next year.

Sir John Armitt, chair of the National Infrastructure Commission, told Building: “The one thing most of us who have ever been involved in a restoration project know is that scope of works is very difficult to define; you will constantly uncover things which were unexpected and that’s going to lead to extra cost and delay.”

Having parliament, rather than the government, as the client for the programme, is “an unsatisfactory situation,” he said.

“We have all the ingredients here for something which is likely to be a constant source of debate, argument, political chancery in the sense of people trying to make political mileage out of anything that goes wrong and therefore probably the worst recipe for delivering something successfully.”

Commenting on the plans to transform Richmond House into a temporary new home for MPs, Armitt said: “Are we trying to build something which is simply as cheap and as functional as we can possibly achieve or are we trying to build a monument to some architectural vanity?”

The risks

Liz Peace, chair of the shadow sponsor board of the restoration and renewal project, estimates that the Westminster refurb could take up to eight years to complete and dismissed the Deloitte cost estimates as “indicative” figures.

She stressed the need for progress: “The fire at Notre-Dame has shown the potential danger of an old building in the state that our Palace of Westminster is in.”

Noting that a building of this age is at its most vulnerable when it is actually being worked on, Peace pledged “a massive focus on fire suppression during the course of the actual construction.”

One source close to the programme told Building: “The building is completely shot, particularly the services, it’s a fire hazard. It leaks, it floods, it’s a complete mess.”

The source predicted that the refurb will run over budget and take longer than expected. And of course, the longer it takes to get the work done, the more at risk the building is. There have been at least 69 fires recorded in the Palace of Westminster over the past decade.

Mounting concern over the danger has prompted £39m to be spent on fire safety improvements over the past year. The palace’s fire safety team is made up of 32 people, with 24 of those being fire safety officers patrolling the Palace of Westminster around the clock.

Tom Healey, programme director of the restoration and renewal programme, told Building: “We are doing everything we can to protect the safety of the people in the building but the problem is if a fire took hold we wouldn’t necessarily be able to prevent the spread.”

CH2M, which was bought by Jacobs in 2017, is leading on programme, project and costs management, with BDP advising on architectural and engineering services on the Westminster refurb project.

It will be the “biggest and most complex renovation programme of any single building this country has known,” according to the Houses of Parliament restoration and renewal programme.

One source close to the programme told Building the costs will be far more than people think. “My best guess would be a minimum of £10bn; that’s where the business case is going to come in.”

Andrea Leadsom MP, leader of the House of Commons, told Building: “The complexity of the Palace of Westminster restoration project reflects the complexity of the building itself, which is why it’s so important we use construction sector expertise to keep costs down.”

She added: “After the terrible fire at Notre-Dame, we must be rigorous in ensuring we do everything possible to safeguard the seat of our democracy for future generations.”

But with work not expected to start for at least six years, in a best-case scenario, many uncertainties, not least the eventual scope of works and budgets, remain. One thing is certain: nobody wants a repeat of what happened in 1834, when the Palace of Westminster was devastated by fire and a seven-year timescale to rebuild it ended up taking some 36 years.

Restoring the Palace of Westminster to its former glory could be a great showcase for British construction, but represents a huge reputational risk to those taking the job on. In the meantime, the 24-hour fire patrols in parliament are a sobering reminder of the need for no further delays.

The Palace in numbers

◼ Total internal area: 112,476m2

◼ More than 1,100 rooms, 100 staircases and 31 lifts in the palace precincts

◼ 128 MEP plant rooms, 80% in the basement

◼ 98 distribution risers throughout the palace

◼ 778 radiators

◼ 100 electric distribution boards

◼ More than 3km of passages set over seven levels

◼ 2km of basement corridors

◼ 11km steam system

◼ 4,000 windows

◼ 1 mile of basement corridors

◼ 2km high voltage cabling, 150km low voltage cabling

◼ 250 miles of other Cabling: 50 miles of Telephone cables, 110 miles of network cables, 30 miles of Broadcasting / sound cables

No comments yet