Housing As the UK dries out after the floods, the idea of a river view may not be as appealing as it was. But these houses in Holland are designed to rise as the water does. Bill Holdsworth finds out how they work, and whether they could catch on in Sheffield

The summer floods in England caused £3bn worth of damage, ravaged 40,000 homes and affected 856 schools. The bad news is that climate change makes worse floods a near certainty.

Already, 10% of homes in England and Wales are at risk from coastal and inland flooding, and we are planning to build many more houses on flood plains. The Association of British Insurers estimates that if no steps

are taken to manage flood risk, the government’s plan to build 3 million homes in 13 years could increase the cost of repairing flood-damaged homes by £21m a year.

The aim of planners and designers is to find a way of building homes that resist flooding, and it may be that the Dutch have found a way to do that. This is not wholly surprising – Holland has had 600 years of experience in keeping sea and river water away from buildings. What is more unusual is that the Dutch have now concluded that, rather than draining water away as quickly as possible, they should allow it to find its natural level.

This policy, which is called “room for the river”, shuns traditional construction in favour of houses that float upwards as waters rise. There is growing consensus among British engineers that serious consideration should be given to the Dutch solutions.

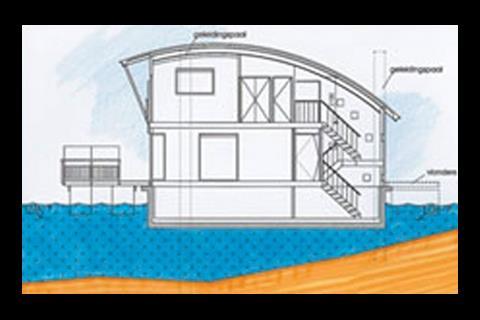

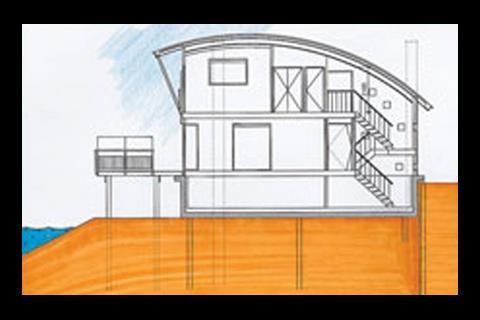

A cluster of floating homes in Maasbommel, near the German border, is one example of how Holland has adapted to flooding. The 46 amphibious houses were built by the Dutch construction company Dura Vermeer in 2006, next to the edge of a dyke that holds back the river Maas. Sixteen of the houses float permanently on the water. They are two-storey, timber-frame structures that are built on precast, watertight, concrete boxes, measuring 10 × 20 × 1.2m. The boxes are buoyant enough to support the houses, and double up as storage space.

Lorries transport the concrete boxes, which are floated into place. They are held in position by pairs of concrete piles that prevent lateral movement, while allowing the boxes to rise and fall with the changing level of the river. The houses have flexible water, sewer and electrical connections, similar to those used for moored houseboats.

On higher ground, there are 30 similar houses, placed 1m above the normal waterline. These sit on concrete slabs. If the water rises, the homes float up.

All 46 houses on the Maasbommel development can withstand a 4m rise in water level, which has yet to be exceeded. Fifteen similar sites in Holland have now been designated for developments based on the Maasbommel prototype.

The success of the project inspired Dura Vermeer to take the design and modify it into a product called FlexBase, designed for permanently floating homes. It differs from the original model in that pontoons are constructed directly on the water. This is done using large polystyrene blocks, which are floated into position and linked together. A concrete slab is then poured on top and the houses are built directly on that. The polystyrene blocks can be linked together to create an area of up to 50m2.

A similar product is being developed by manufacturer Aqua Life Nederland.

The base comprises two concrete shells with a space between them through which the water, power and sewer pipes can be routed. Like the Maasbommel houses, concrete piles moor the building, but can rise with the water.

Aqua Life’s platforms are prefabricated and transported to site. The concrete shells are designed to withstand the high stresses induced by the movement of surrounding water and the impact of wind. Construction costs for these amphibious foundations are *250-350/m2 (£171-240) but both manufacturers believe that, with increasing demand, costs will fall.

Could a similar system be adopted in the UK? Mark Southgate, head of planning and environmental assessment for the Environment Agency, is cautious. “In Holland, where 55% of the land mass is below sea level, people are creating solutions that are particular to the country’s needs,” he says. “This is not the case for most of the UK.”

In the UK the focus is on locating developments in lower flood risk areas. Southgate says: “Government planning policy [PPS 25] clearly indicates that significant flood risk areas [flood plains with a one in 75 risk of flooding each year] should only be used when no other locations are available.”

Other experts are more enthusiastic. Ian Batty, a structural engineer and part-time lecturer, has been looking into the idea of floating homes for engineering consultant White Young Green. He says the system might be the answer for significant flood risk areas. “The same design could be brought to the UK and adopted quite easily for use in areas susceptible to flooding,” he says. “If we can build on high-risk flood plains, we may avoid having to open up the green belt.”

Batty sees another advantage, too: the houses are quick to build. The site is simply cleared to create a level base and the pontoons are moved into position. The lightweight houses are then constructed directly onto the pontoons, which provide a ready-made alternative to solid foundations.

So, they’re easy to build and an answer to the green-belt problem. Perhaps Gordon Brown should give Batty a call …

Postscript

For more on flood-resilient homes, search www.building.co.uk/archive

Topics

Specifier 21 September 2007

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Permeable paving: So what if it’s raining?

- 12

- 13

- 14

No comments yet