Joey Gardiner scrutinises the Tories’ plans to extend right to buy to housing associations

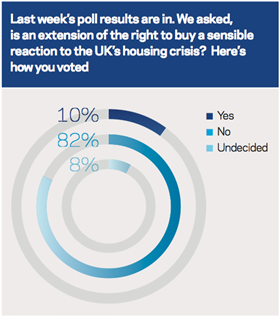

There’s no doubt that the big built environment issue of the election campaign last week was Conservative Party plans to extend the historic right to buy to housing associations. So to kick off our in-depth coverage of the election countdown this week, we have a look at what this policy could really mean for construction of social housing in the UK.

Certainly the social housing sector was very quick to pour scorn on the proposals from the Conservatives, with one housing association chief executive saying he would “definitely” launch a legal challenge against any such moves, and many others saying it would jeopardise the hard-won financial position of housing associations which allows them to develop new homes. The backlash from the policy’s supporters in the press was brutal and equally rapid: “hypocritical” housing association chief executives opposing the policy found pictures of themselves and their “lavish” houses plastered on the front page of the Daily Mail next to their “six figure salaries”.

It seems unlikely right to buy can add up, but I’m not sure they care as it’s a political gesture, it’s not about policy

Andrew Heywood, Housing Finance international

While there are many unanswered questions about the Conservative Party’s proposals, the basic premise is that it will extend the fund’s huge discounts given under the right to buy sales - £77k in England rising to £103k in London - to 1.3 million tenants of housing associations. It will pay for it by forcing councils to sell off their most expensive homes when they become vacant. By selling 15,000 of these a year, the Conservatives say they can raise £4.5bn annually - implying an average sale price of £300k for these homes. The resulting cash will have to not only fund the replacement of these council homes with “normal” affordable housing, but also pay off any debts associated with the council home, fund the right to buy discount, and contribute to a £1bn brownfield regeneration fund.

The Conservatives said a future Tory government would guarantee one-for-one replacement of the homes under the policy, and that by releasing local authority cash, it would see more money spent on building new homes, thereby adding to the overall housing stock in the UK. However, the National Housing Federation pointed to the fact that fewer than half of the homes sold under local authority right to buy have ever been replaced, and said the requirement to sell council housing to fund the policy meant that for every right to buy sale, effectively two affordable homes were being lost.

So with both sides in the debate arguing it out, do the dire predictions of the housing associations stand up to scrutiny?

Do the numbers stack up?

Most in the sector struggle to see how the sale of the UK’s most expensive council homes - leaving aside the social question of whether losing council housing in expensive areas is the right thing to do - can bring in enough money to do everything that is being asked of it. If housing association homes were sold off at the same speed as council homes in 2013/14, then almost 9,000 would be sold each year. This means, using an average discount under right to buy, each council house sale could be expected to have to contribute about £35k to pay for the discounts for housing association right to buy. This would be alongside a contribution of £13k to the brownfield regeneration fund, an unknown figure to support council housing debt and paying for the replacement council home.

Andrew Heywood, former senior policy adviser at the Council of Mortgage Lenders, now editor of Housing Finance International, says: “It seems unlikely it can add up, but I’m not sure they care as it’s a political gesture, it’s not about policy.”

However, even if that money can be made to stretch that far, there is a question about whether it is a cost-effective way of achieving the outcome generated. Kerry Kyriacou, director of new business and development at social landlord Affinity Sutton, says: “Right to buy discounts are anything up to £80k while shared ownership grant per property is on average around £20k.

If your aim is to support people into home ownership, that seems much better value for the public purse.”

Will it make it harder for housing associations to develop?

The immediate response to the proposal from housing associations was to suggest it would damage their ability to take out secured loans against their existing housing stock, because it would diminish the number of homes they held and their rental income. This is vitally important because, with grant rates already cut back, housing associations must borrow on private markets the vast majority of the funding needed for new home construction. Certainly credit ratings agencies, including Fitch, have already made it clear that an extension of right to buy would force them to re-evaluate how risky the sector is to lenders. Fitch said last week that with right to buy: “Registered providers’ borrowing capacity could be constrained as their balance sheets would weaken and the value of their available housing assets pledged for borrowings would decrease. This would constrain the registered providers’ overall capacity to borrow.” Currently the housing association sector has £60bn of private sector loans taken out, which it uses to help it build between 20,000-25,000 houses each year. Any change in the price of those loans could have a big impact on their financial headroom to spend on new building.

More seriously still, the sale of homes could even make some default on existing loan terms. Heywood says: “If a particular house is a security for a loan, you could be in a position technically where you default on your loan covenant by selling. At the very least you may have to get the permission of your lender - and what happens if he says no? Housing associations’ financial capacity would be seriously eroded unless they are fully compensated for these sales.”

Is it likely to end up in the courts?

The National Housing Federation has been clear that it doesn’t believe the government has the power to force housing associations to sell homes, and much of the sector agrees with this stance. The government could attempt to use its regulatory role, enforced by the Homes and Communities Agency, over housing associations to force them to sell homes, but this is likely to be resisted. The chief executive of South Yorkshire Housing Group, Tony Stacey, has already gone public in saying he would challenge any attempt under the current laws to force associations to sell homes. As well as putting loans in jeopardy, the policy could also breach laws which prevent charitable bodies from selling assets at beneath their market value - the issue which prevented housing associations being brought in to right to buy when the policy was originally set up by Margaret Thatcher’s government. Dale Meredith, development director at Southern Housing Group, says: “We’d be resisting it in any way we could. We don’t think the government can do it now.” The government could, of course, change the law to give it the power to do so, but this would also be fraught with difficulties as it could end up seeing housing associations re-classified as public sector bodies. If so, then the sector’s £60bn debt, equivalent to 3-4% of GDP, would go back on the government’s balance sheet - something the government has so far been keen to avoid. Meredith adds: “It doesn’t make sense for us. If it was forced on us, it would raise issues about whether we are private or public sector bodies, and about our charitable status. And it misses the point that the real problem is there just aren’t enough affordable homes.”

The other parties’ right to buy policies

Labour has said that it supports right to buy in principle, while branding the proposed Tory extension as “uncosted” and “unfunded”. Labour’s manifesto pledges to secure a one-for-one replacement for every council home sold under the right to buy. The party’s recent Lyons review of housing recommended that the next government should review how receipts from right to buy sales are distributed.

The Liberal Democrats have said that full control over right to buy will be devolved to local councils. The Greens have pledged to scrap discounts on right to buy sales, which the party identifies as one of the key causes of what they describe as the chaos bedevilling the housing market. UKIP takes a different tack, pledging to ban foreign nationals from exercising the right to buy.

No comments yet