Purcell Miller Tritton’s lavish £22m restoration has returned Liverpool’s grade I-listed St George’s Hall to its glorious past – just with fewer prisoners and hopefully more tourists.

Of the all the great buildings of Liverpool’s past, the most magnificent is St George’s Hall. It was completed by the city council in 1854 in the same flush of civic pride that produced Birmingham Town Hall. Like its Midlands counterpart, it has just been lavishly restored at a cost of £22m and was reopened on St George’s Day (23 April) by Prince Charles.

Larger than Birmingham Town Hall, St George resembles a supersized Greek temple, bounded on all four sides by giant limestone Corinthian colonnades. Even Sir Nikolaus Pevsner, the legendary architectural historian, and not a man given to gushing, called it “one of the finest neo-Grecian buildings in the world”.

The building is testament to the architectural genius of Harvey Lonsdale Elmes, who won a national competition to design it at the tender age of 23 but succumbed to tuberculosis before it was completed. A hidden marvel of the building is what is claimed to be the world’s first air-conditioning system, supplying both heated and cooled air. This was devised by Dr David Boswell Reid, who installed a more widely publicised, if less audacious, ventilation system in Sir Charles Barry’s Palace of Westminster.

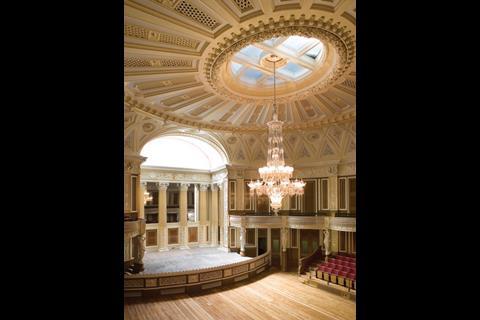

St George’s Hall was planned for a bizarre collection of uses. The great and the good of Liverpool society could glide in through the Doric stone columns of the apsidal north entrance to attend concerts in the sumptuous semi-circular concert hall directly above it or partake in civic functions in the great hall at the heart of the building. Meanwhile, prisoners on remand would be frog-marched through a basement side entrance to await trial in either the crown court or the civil court at either end of the building.

Long-term problems were caused by the building’s hybrid function and its grade I-listed status. When the courts moved out to new premises in 1984, no overall use for the building could be found by the city council and, except for the main hall, it was mothballed. The neglect led to severe deterioration, as leaking roofs caused dry rot and the collapse of plastered ceilings.

In 1997, the council commissioned conservation architect, Purcell Miller Tritton, to restore and convert the building, and it gathered together £22m in funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund, European and central governments and various charities.

The solution devised by the council and Purcell Miller Tritton came in three parts:

- The two great halls have been faithfully restored for their original musical and civic functions

- The two courtrooms and prisoners’ cells below have, likewise, been restored, this time as a heritage visitor centre rather than for their original uses

- The main alteration has been to convert the cavernous undercroft into a visitor centre.

The two courtrooms are in a more sombre classical style, with barrel-vaulted ceilings supported on Corinthian columns of polished granite in pink and grey. Each courtroom was originally divided up into a geometrical maze by waist-height oak partitions. These have been restored and later additions removed.

The great hall was restored in the nineties, and has largely been left alone. The only change here has been to drive a walkway through the existing rows of benches along one of the side galleries. From the floor of the hall, the only visible change is new balustrading required to comply with modern safety regulations. Frameless glazing in colourless low-iron glass was specified for the balustrading, which is openly contemporary in style yet inconspicuous.

The massive undercroft has undergone extensive alterations to convert it into a visitor centre. According to Robert Chambers, the project architect, the undercroft was originally a labyrinth of high brick vaulted cells, many of which housed the bulky steam boilers, ducts and pipes of Boswell Reid’s pioneering air-conditioning system. The new, more compact and versatile air-handling plant can be conveniently hidden in the roof, thereby freeing up the basement.

Brick partitions were knocked through to create a cohesive network of interconnecting spaces. These serve variously as a reception lobby, display area, shop and cloakroom. Two larger spaces in the heart of the undercroft have been converted into a pair of interlinked entrance halls, and a staircase has been dropped in to link them to the main ground floor overhead.

The alterations in the undercroft have been carried out in a discreet modern style using frameless glazing and stainless steel handrails. The ubiquitous raw brick walls and vaults are illuminated to powerful effect by uplighters in the York stone floor slabs.

A new main entrance to the visitor centre has been cut into the external wall from the lower pavement level. Here, however, the style is not modern but neo-classical. The entrance was created by dismantling a few of the original cladding panels in purple-tinged ashlar and carving them into the new door surrounds. They are in a faintly Egyptian style that faithfully matches the treatment of the original wall.

The final component of the conversion has been to extend two original public staircases down to the basement and here, again, the style is traditional. They were originally built to lead up to the upper-level concert hall and great hall galleries, and connecting them to the basement allows these two halls to be reached independently from the rest of the building. As the extensions serve the same function as the original staircases, they are carried out in identical material and constructed to match. This entailed the intricate traditional technique of cantilevering stone slabs out from the staircase brick wall and bonding them snugly together to provide mutual structural support.

According to council leader Mike Storey, the project “will open up St George’s to many more people and we will be able to stage a much greater programme of events, from performances to conferences and banquets”. In this way, St George's Hall will serve as an inspiring venue for the European Capital of Culture next year.

Project team

Client Liverpool council

Architect Purcell Miller Tritton

Project manager Mouchel Parkman with Liverpool council

Structural engineer Morton Partnership

Services engineer William Hannan Associates

Cost consultants Davis Langdon and Cyril Sweett

Main contractors Mowlem Special Projects and Linford Group

Building services contractor Mitie Engineering

Stone restoration Bullen Conservation

Decoration Roy Hankinson

Plaster restoration Chris Cook

Downloads

Floor plans

Other, Size 0 kb

No comments yet