Since January, nine people have died in crane collapses in New York. The response? Tough safety rules, which the city council says will prevent death, and the industry says will make life impossible.

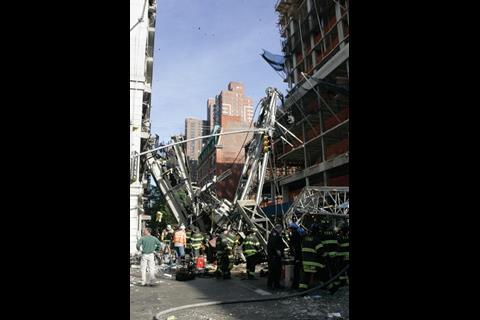

On 15 March this year, there was a terrifying accident on the east side of midtown Manhattan. A 19-storey crane came loose from the luxury apartment block it was anchored to, splintered into pieces and crashed over 51st Street. The 75-foot boom and its cab were catapulted over a roof and destroyed a townhouse. Seventeen people were injured and seven died – the six workers “jumping” the crane and a 28-year-old Florida woman in town to celebrate St Patrick’s day. An eye witness quoted in the New York Post, said: “When it landed, it was like an earthquake. We ran out. The dust was like the World Trade Centre.”

The incident was the first of a string of events that culminated last month in a tough city law on crane safety. But is this hurriedly introduced legislation any good, and can the UK learn anything from it?

As the ancestral home of the skyscraper, New York has prided itself on its technical prowess. Those black and white photographs of the men that built the Empire State building and the like eating their lunch on spindly beams are among the enduring images of New York. Louis Coletti is president and chief executive of the Building Trades Employers’ Association, which represents US contractors. He says: “We’re the home of the high rise; we know how to build these things.”

So this year’s spate of crane accidents in New York has come as a shock to the city. After the carnage of the 51st Street accident, a second crane collapse on 30 May killed two workers (see timeline, right). This accident, on a site at First Avenue and 91st Street, fuelled the panic. By June, the New York City Department of Buildings (DOB) had received 100 complaints from the public about “unsafe and illegal” cranes. Then came the arrest of a senior city crane inspector: James Delayo was accused of falsifying inspections in return for money.

More deaths followed, such as that of Anthony Esposito, 48, who was helping dismantle a crane for specialist DFC Structures last month when he fell 40 storeys. That brought the death toll on New York’s construction sites this year to 20, including nine in two crane collapses.

Coletti says the underlying cause is the intensity of construction activity in the city over the past few years. “The market had got so busy that there was a shortage of contractors experienced in New York high-rise buildings, so less experienced people started operating here,” says Coletti.

With the city gripped with fear over crane safety, few doubted that something had to be done. As Coletti says: “We were in favour of anything that improved safety.” So in September New York City council voted in rules on tower and climber cranes. Now, by law, before a crane is erected, jumped or dismantled, a plan must be filed with the DOB. There must also be safety meetings on site, with the minutes kept on site for DOB inspection.

The new law says that anyone operating a tower or climber crane must attend a 30-hour training course with refreshers every three years. Controversially, the legislation also limits the use of the synthetic webbing used to carry materials. These “nylon slings” have broken in accidents, but not everyone agrees that they are dangerous.

Penalties for breaking the law are tough. For example, if someone does not complete the 30-hour training course, they will lose their licence. Sites flouting the rules will be shut down indefinitely, although the law stops short of shutting down businesses.

Councillor Erik Martin Dillan defends the legislation: “Whenever something weighing 40 tonnes falls 40 storeys, people pay attention. The public has really demanded we do something about crane safety in New York. We have made sure the regulations are totally fair. Everyone has been made aware of them and so everyone should know that with the appropriate training and inspections of equipment, nobody will get fined or penalised.”

But this does not mean that New York’s construction industry agrees with the new law. Coletti says: “The intentions behind the legislation are good but the law they have passed is problematic.” Ray McGuire, general counsel for the Contractors’ Association of New York, which represents high-rise builders, says there is no question of people intentionally breaking this law. “At a time when we are seeing a significant decline in workload – there are 130,000 construction workers in New York City and 30,000 will be laid off in the coming months – nobody can afford a stop work order.”

Much of the law is unnecessary. I’ve been doing this work in New York for 18 years and I can tell you people don’t take short cuts here

Peter Stroh, Stroh Engineering

However, both McGuire and Coletti are angry about the idea of the DOB checking all plans for working with cranes and the records of safety meetings. The DOB does not have this capacity itself so it needs to employ a crane specialist known as an “engineer of record” to do the job. To say engineers of record are in short supply in New York would be an understatement. Worse still, they are deeply unhappy with the situation. For a start, they are short staffed. There are just three small companies in the city that employ them. One is understood to have refused to work with DOB and the other two, Stroh Engineering Services and Howard I Shapiro, have three engineers of record between them. Coletti is worried this could hold up work. He says: “We’re looking at construction coming to a screeching halt.”

Their other problem is that they cannot get insurance to cover their responsibilities under the new law. Peter Stroh, of Stroh Engineering Services, was the engineer on the crane that collapsed at 51st Street. He says he’s all in favour of improving safety: “I fully understand the consequences of a bad design or shoddy workmanship … We are doing the assessments but [Howard I Shapiro and our firm] have told the city council it’s only for now because our insurance doesn’t cover us. We’ve been going back and forth to the authorities and trying to figure out a way of moving forward.”

Stroh adds that much of the new legislation is unnecessary. The safety meetings that must be held before jumping a crane were happening anyway, he says. “I’ve been doing this work in New York for 18 years and I can tell you people don’t take short cuts here.” Also, the virtual outlawing of nylon slings is “irrational”. “As long as synthetic slings are not worn out they make a lot of sense, especially for rigging purposes.”

Other elements of the law are seen as impractical. The requirement to check a crane’s manual every time it’s moved, for example, means “we’ll be doing more administration than engineering”.

Stroh says the city council rushed through the legislation without consulting properly with the people at the sharp end. “Politicians have written this law, not technical people. We tried to talk to them – I said let’s make this workable, not a knee-jerk reaction – but we got nowhere. As a result, I think the city has acted in haste and failed to accomplish what they intended. They haven’t actually accomplished anything safety-wise.”

The DOB declined to comment but the city council has said more legislation is on the way, so there is hope that the industry’s concerns may be met. Among other initiatives the council is asking the UK’s Health and Safety Executive (HSE) for advice. But could this work both ways?

Back in the UK, John Spanswick, chair of the Strategic Forum’s tower crane group, says the UK industry already practisse most of the New York measures. Under the CDM regulations, similar plans must be drawn up and safety meetings held before a crane is erected, jumped or dismantled, and the local authority kept informed. The requirement to refresh training every three years in New York goes further than ours – you only need to renew your ConstructionSkills Construction Plant Competence Scheme card every five years here. The ruling on synthetic slings has bemused UK observers. Spanswick says: “I think they’re going over the top. But I actually applaud them for it. It’s worth it if it gets the message through.”

But he does not feel there is the same need for drastic action in the UK. “We don’t have anything like the number of crane accidents they’ve had in New York.” He adds that improvements to crane safety, some of which were called for in Building’s Safer Skylines campaign, are continuing in the UK. A recent move was the Strategic Forum’s publication of its Tower Crane Working Conditions Best Practice Guidance, available at its website www.safecrane.org.uk/downloads.

Colin Wood, chief executive of the Construction Plant Hire Association, agrees. “We’re doing okay here. The fact that the HSE is advising New York shows it’s not so much what we can learn from them as vice versa.”

Over in New York, the construction industry remains sceptical about the new law. McGuire says: “Everybody in construction is looking closely at the situation. Nobody wants to see anyone carried off a construction site in a hearse so if more change is needed, you’ll see it coming from the industry faster than from the DOB.”

Original print headline - The incident on 51st

New York

The city where the future happens first

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

The incident on 51st: Crane safety in New York

- 7

- 8

No comments yet