Alright, so it might not win the Man Booker Prize, but the tale of how Birmingham council spent 10 years trying to get its new central library off the drawing board has got the critics gasping.

It has all the ingredients of the type of well-thumbed yarn that keeps public libraries in business – apart from, somewhat crucially, an ending. When Birmingham council proposed building a new central library 10 years ago, it could hardly have expected the decade of political infighting that has been the central theme of this story. Nor could it have predicted the fates that awaited many of the leading characters: several of the city’s foremost politicians are nursing injured reputations, and one of the country’s most revered architects was written out of the story halfway through.

The plot revolves around replacing the seventies-built central library, which Prince Charles once likened to an incinerator, with a shining icon of the city’s regeneration. However, changes to the architect’s brief, the location and the budget ensure that there are plenty of twists. The latest chapter opens with more than 100 architects vying to finally build the project, now priced at £193m. But before we come to that, perhaps it’s best to start at the beginning …

Chapter one: Setting the scene

Built in 1974 for a then eyebrow-raising £3.5m, Birmingham Central Library was “stark and forbidding” (and that was according to the chairman of the city’s library committee). It was intended to last for more than 100 years. With 1.5 million visitors a year (one for every book on its 31 miles of stacks), it was the busiest public library in the UK. It is the third incarnation of the central library; the first was opened in 1865. This long history has made it an important symbol to the people of Birmingham.

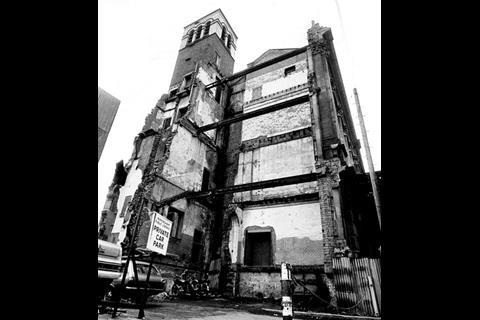

However, by the late nineties the building was crumbling. Water had seeped into the metal mesh in the library’s concrete structure while a fire in the early nineties had destroyed the children’s library and damaged the lower floors. According to one Birmingham council source, concrete was actually falling off the building.

The Labour leader of the council, Sir Albert Bore, started toying with refurbishing and extending the library along the lines of a second stage of development that had been drawn up by the architect John Madin in the seventies. However, the slope of the building made such an extension difficult and costly. By the turn of the millennium, Bore had settled on building a new library that would be the focus of the Eastside regeneration scheme, a 15-minute walk east of the city centre.

This was to be an architectural competition that would appeal to a new wave of designers entranced by the Labour government’s obsession with the notion of regeneration. Launched in late 2001, bidders were specifically asked not to design a building. Instead, architects had to write what they thought about the purpose of libraries on five sheets of A4 paper.

Perhaps more surprisingly, it was also decided that the winning architect would not be hampered by the constraints of a fixed budget. Instead, the firm would work to a £150-200m “frame of reference”, according to Brian Gambles, Birmingham council’s assistant director for culture, a man who has worked on the project from the start.

The Richard Rogers Partnership won the scheme in May 2002, but the lack of a fixed budget would prove the project’s undoing.

Chapter two: Conflict

Rogers and the council went through an onerous consultation process – 4,000 children were among those canvassed for their opinions – while quantity surveyor Gleeds ran the numbers for the architect’s developing vision. It was becoming apparent that fixing a design before a budget was the wrong way round: “Rogers looked at a smaller scheme that would take some cost out,” says a source close to the design team. “It’s annoying to do a competition and find out six months later that you don’t have money to build it.”

Opposition was mounting. Some wanted to see the restoration of the existing library. Alan Clawley, a one-time architect who had moved into community work, started what he describes as a “one-person letter writing campaign”, which six years later has developed into a 60-strong group called Friends of the Central Library. “I responded to the idea that it was ‘crumbling’ – there was no evidence that it was about to fall down,” says Clawley, who has run a series of exhibitions and meetings to curry support for the existing structure.

More disruptive was the change of political leadership brought by the 2004 local elections. For the first time in 20 years the council was not under Labour control, moving instead to a Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition. Soon after the election, the coalition met with Rogers. “The meeting was awful,” says one attendee. “It was very clear the scheme was not what they wanted.”

A council source adds that the new administration was horrified by the lack of an agreed budget: “The new council planted its political flag – fiscal discipline, freezing things that didn’t have a budget for 12 months. There was at least one meeting regarded by the Richard Rogers Partnership as pretty challenging. They started distancing themselves.”

Chapter three: New characters

The problem for the new council leader, Mike Whitby, was that freezing the plans for ostensibly sensible financial reasons soon looked to the local media like dithering. Rogers’ plans had effectively been shelved, and instead Whitby started promoting a split-site solution, which would see a lending library built on a car park next to the Repertory Theatre in Centenary Square, close to the current location, and a city archives and reference section at Eastside.

Consultant Invigour confirmed that the split-site idea would be cheaper than Rogers’ plans, at £147.4m compared with £179.5m.

In May the following year, 2006, concepts by architects Make, Glenn Howells Associates and Adjaye Associates were shortlisted as possible designs for the Centenary Square location. Whitby’s praise of the new designs effectively ended Rogers’ participation in the project: “This is the perfect answer to those that claimed we would be unable to produce a library of any quality if we did not choose the Richard Rogers scheme at Eastside.”

The split-site idea was unpopular within the council; officials eventually managed to persuade Whitby that all the facilities should be at one location. But the Centenary Square spot remained popular: “That site is where the footfall actually is, rather than out in the sticks,” argues a council official.

In August 2006, Capita Symonds was the latest consultant – Gardiner & Theobald and Jura had produced earlier reports – to be parachuted in by the council. As one frustrated source close to the project puts it: “There have been more consultants through the door than you’ve had hot dinners.”

A plan emerged to use the car park site to accommodate all of the library’s facilities. There were, and still are, accusations that the location was too small. At first, it looked like a building would have to comprise 13 floors: four underground and nine above. This idea was dropped on the grounds that it would overshadow Baskerville House, a former civic centre built in the thirties.

Another plan was hatched. If half of the neighbouring Repertory Theatre was knocked down, the library would need just 11 floors, seven above ground. The theatre’s facilities need updating anyway, say the plan’s proponents, and this scheme will have less impact on the skyline. The theatre and library will merge, sharing several services, such as a cafe. The plans were unveiled last October, just over a year after Capita Symonds was appointed, and the intention is to complete the project by summer 2013. This is the scheme that is now undergoing an international design competition – which Rogers confirms it has not entered. It still has its critics, however, and there remain threats to the plan’s future.

Chapter four: Further twists

The scheme has been accused of being too small, cut from 38,000m2 to 31,000m2. Supporters say that IT advances have made much referencing and research available by computer, cutting down the space that was required at the start of the decade.

Then there are several thorny issues around cost. The price tag is £193m, more expensive than the Rogers scheme. However, using like-for-like figures, including construction inflation, the Rogers library would now weigh in at about £40m more. But then Rogers’ scheme was never value-engineered; a source close to the council says that the figure could have been “brought down without question”. In the end the difference in cost appears to be minor.

More significantly, there is a £39m funding gap, to be underwritten by the council. Officials will have to find the money to cover this through grants and private contributions. For a council so determined to kill the Rogers scheme over budgetary concerns, it seems odd to many that the current administration is happy to proceed without accounting for every single penny in advance.

There is one final issue that has simmered for years, but is only now being aired: the existing library itself. One of the key reasons to leave the site is to help with the £1bn regeneration of Paradise Circus, a proposal that has been in development for more than seven years. John Madin, the 83-year-old architect of the library, is convinced that the commercial gain from this plan is the reason his flawed masterpiece faces a wrecking ball. “It is a great sadness that the sole purpose is to sell off Paradise Circus – the central library is obstructing that sale,” he argues.

Madin also questions council estimates that the library would cost about £160m to refurbish and extend, arguing that the real amount is closer to £30m. Even the Labour opposition, though, believes that the cost is at least £100-120m.

Furthermore, the architect attacks council suggestions that the building does not meet disability needs by only having one public lift. There are four lifts in the building but three are used for staff and goods. Madin says these could be better allocated. “There has been a planned lack of maintenance [since the decision to sell],” says Madin, who says the escalators have not been maintained “for five or six years”. Council official Gambles denies this, saying that £3-4m was spent on refurbishing the escalators in 2001 and that they are under guarantee until 2009.

There is one final twist. Friends of Central Library has approached English Heritage to list the building. It seems inevitable that the government will decide whether or not to agree to a listing in April. If successful, this would stop the development of the building. A sale would then be unlikely and put the whole £1bn development in doubt.

However, a council insider insists that this would not alter plans for a new library on that car park in Centenary Square: “A listing would not stop us.”

It would, however, add yet another chapter to this long and sorry tale.

Borrowed time: the struggle for a new central library

1865

Birmingham Central Library opens

1879

Fire devastates the building, prompting a re-build

1974

Third incarnation of library opens

2001

Architecture competition launched to design fourth incarnation

2002

Richard Rogers Partnership wins the job, cost will be at least £150m

2004

Council changes from Labour to Tory-Lib Dem coalition and Rogers scheme is dropped

2006

Another architecture competition is launched

2007

£193m is price of new design, which is £39m over the new council’s original budget

2008

April decision due on whether to list existing building

2013

Due date new building’s planned opening

No comments yet