Need any more evidence of Westfield’s massive ambitions? How about these 14 cranes looming over west London, and the huge mall rising around them. Or the fact that it ditched its contractor to take on this monster of a project by itself.

For anyone passing through White City in west London, it is hard to avoid the new shopping centre under construction. Westfield London is currently a vast site of frenzied activity as workers race to complete five anchor stores, 265 speciality shops, 40 restaurants and leisure facilities. Lorries queue up along the ramp off the motorway to feed the 14 tower cranes that are keeping the project moving.

The 45-acre scheme also includes a new tube station and bus interchange at Shepherd’s Bush, a station for the West London overground line, a new station on the Hammersmith and City line and another bus interchange near the BBC headquarters at White City. It is hoped that the £1.6bn scheme will attract customers from across Greater London, anxious to part with about £5bn a year. But first, developer Westfield has to get the project finished.

Building anything on this scale is a major challenge, but this project has had more than its share of ups and downs. Originally it was being developed by Chelsfield to a plan drawn up in the nineties by Ian Ritchie Architects. Contractor Multiplex had been engaged to do the job and was on site when Australian developer Westfield bought out Chelsfield in December 2004.

This is where things start to get complicated. Westfield had its own ideas about what makes a successful “lifestyle destination” and wanted to change the design. To complicate matters further, Westfield likes to do everything in-house, from design right through to construction. As Iain Johnstone, the company’s development director, puts it: “Self-sufficiency has been our model for the past 30 or 40 years. This makes us responsive to changes in the marketplace and more efficient and improves results.” Having a separate contractor didn’t fit this vision, so it had to find a way to get rid of Multiplex and take over the scheme’s construction itself.

And as if that wasn’t enough, there was also the small matter of a huge Central line depot taking up a third of the site. The plan was to build a replacement depot underground then build over the old one, but complications had put this behind schedule and were threatening to delay the whole project.

So, with the project already showing itself to be a huge, unwieldy beast, the first question is, why on earth didn’t Westfield just leave things as they were? Johnstone says the company always looks carefully at each development to see what it will get out of it, how it is positioned in the market and what will make it appealing to tenants. Get this right and the customers will follow. When it applied this exercise to the original White City designs, it found the scheme didn’t meet its standards. Retail design had moved on since the nineties and the centre would have to compete with established shopping areas nearby. “Oxford Street shops are quite large,” says Johnstone. “We needed to provide a similar offer to attract tenants.”

Westfield decided to make some big changes. These included inserting a mezzanine floor to create a bigger retail area and changing the roof material from ethylene-tetrafluoroethylene to a more appealing glass covering and adding green roofs over some of the unglazed areas to increase biodiversity. Full air-conditioning was introduced, the position of the malls was tweaked and Westfield ditched most of the lifts in favour of escalators, which affected the design of the core and necessitated big apertures in the floorplates. The developer also wanted to change the structure from concrete to steel as it believed this would be more flexible should retailers’ needs change.

The next step was to remove Multiplex. The trouble was that the contractor was already on site building the original scheme when Westfield took over. It had done the piling and procured 65% of the packages. How did Westfield cope with such a major change?

The answer was simple – it took on the Multiplex employees as Westfield employees. “This enabled us to have continuity and maintain the programme,” says Keith Whitmore, Westfield’s director of construction. He says nearly all of the 70-plus Multiplex employees on the project chose to move to Westfield. This helped the developer build up its construction resources for the future. And there was another advantage: “I think I am one of the luckiest construction directors in the industry as I don’t have battles with the contractor,” says Whitmore.

Westfield took over the job in August 2006 and it seems to have been an amicable and smooth transition. Johnstone claims Multiplex accepted that Westfield did things its own way. Flan McNamara, a former Multiplex employee who is now Westfield London’s construction director, agrees: “It suited Multiplex as it was withdrawing from construction in the UK.”

But the minute the site was under Westfield’s control it had the problem of the tube train depot to resolve. Multiplex had been building a £70m, underground 16-train depot to the west of the site. The idea had been for London Underground (LU) to take this over, thus releasing the pre-existing depot, which was slap-bang in the middle of the site, for redevelopment.

The new depot should have been handed over to LU as Westfield walked through the door, but it was not finished yet. “Until we had finished and handed it over, LU wouldn’t release the ground above it,” says Whitmore.

Building the depot was always going to be a big undertaking: its scale, the fact the Central line had to be diverted to connect to the box and the difficulties of working next to a live railway, were all obstacles to overcome. And when there were problems on the Central line that caused trains to be diverted into the old depot, LU took back possession of the areas next to it without any notice.

When Westfield took over, all the heavy work had been done, but the fit-out was still under way. “We took on the challenge to deliver this by Christmas,” says Whitmore.

This challenge was all the greater because LU was a very fussy client. Whitmore cites as an example the safety gates that drivers use once the train has been parked. “You wouldn’t believe the dialogue we had over these gates,” Whitmore says. “Should they be single gates or double gates? Would the drivers be able to locate the gates?” He adds that LU wanted to change the mesh platform surfaces after they were completed, because drivers might drop their keys through them. Fortunately, as mesh was in the original specification, it stayed.

“We piled an enormous amount of time and effort into handing over on time,” says Whitmore. This included working longer hours when necessary, which vindicated the self-sufficient approach. “Becoming part of the client body rather than just being the contractor was one of the real winners,” says McNamara. “If I was the contractor I’d have had to go through a project manager who’d then go back to the client. Now I had the authority to just do it.”

Whitmore hit his target and was ready to hand over the depot just after Christmas 2006. “It was a milestone in the project – we were chomping at the bit,” he says.

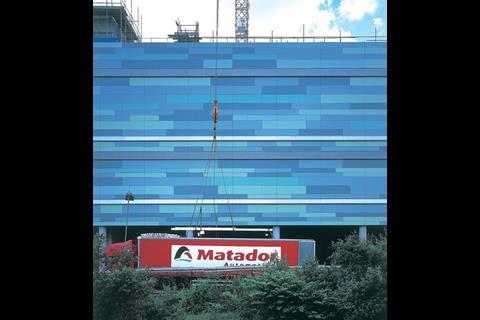

While the depot was being sorted out, Westfield was planning the buildings to be built on the “Blue Lands”, the nickname for the site of the old depot. These were some of the structures that, for speed of construction and greater flexibility, Westfield wanted to switch to steel. It had started the redesign work the day it took over from Multiplex and the steel was fabricated while the depot was being sorted out, allowing work to start the day LU handed the site over.

Westfield also reviewed the programme to see if it could be tightened up. “There is always something you can improve,” says Whitmore.

A good example of this was the tiling in the malls. The original plan was to complete the roof then tile the floors. Instead, the roofing scaffold has been designed so the tiling team can work underneath it and set out the floors – once the scaffolding moves onto the next section, the tiles are laid. “We’ve saved 20 weeks on that part of the programme,” says Whitmore.

Other changes to the design were also accommodated without much difficulty. “The clever bit was to incorporate these changes into the existing design, as all the piles were in place,” says McNamara. The piles were able to take the additional weight of the structure but the structural columns were now in the wrong place. This was solved by using transfer structures in the underground car park to switch loads to the new locations – all done without losing any parking spaces.

Now Westfield has resolved the design problems, it is cracking on with the job. It has taken full control of the cranes rather than leaving them in the hands of specialists so it can control the movement of materials. Piling and the cores are complete on the Blue Lands and the steelwork is pressing ahead – at the moment, there are 12 deliveries of steel a day.

Whitmore says the overall programme is on track to be finished by the end of next year – any areas that have slipped are balanced by others that are ahead. Which will be music to the ears of the shopaholics of west London …

Shop till you drop

Westfield has already secured five anchor tenants for the site: Marks & Spencer, Debenhams, House of Fraser, Waitrose and Next. There are also 265 speciality shops, a cinema, a gymnasium and health and beauty retreat, which all adds up to what Westfield describes as a “lifestyle destination”.

The south side of the development has a pedestrian thoroughfare that will be lined with restaurants and bars. Another walkway passes diagonally through the site and links Shepherd’s Bush tube on the south-eastern corner to the BBC’s television centre to the north-west.

Shopping centres live or die on their location, and Westfield London could hardly be better placed. It is next to the A40, which brings in traffic from the west, and will also be extremely well served by public transport. “In my experience, having this level of public transport infrastructure works is quite extraordinary,” says development director Johnstone. “We anticipate 60% of our patronage will come by public transport.”

This includes £100m of public transport improvements including two tube stations, an overground stop and two bus interchanges.

Project team

Developer Westfield

Architect Westfield/Buchan Group International

Design-and-build contractor Westfield

Engineer Robert Bird & Partners

Quantity surveyor Westfield/Davis Langdon

Concrete works PC Harrington

Structural steel Severfield Reeve

Mall glazed roofs Waagner Biro/Seele

Flat roofs Prater

Facade Scheldebouw/Parry Bowen electrical T Clarke

Mechanical Rotary/Meica sprinklers Argus

Block/brickwork Swift drywall BDL

Downloads

Westfield London in plan

Other, Size 0 kb

No comments yet