Let's take an office complex as an example. We can all appreciate the benefits of working in an environment where the temperature is precisely regulated and, for offices, in the summer, the optimum temperature setting is 24°C, with a narrow differential of ±4°C. However, in many of today's office developments this temperature band can soon be exceeded, especially during the hotter summer months, due to the effect of solar radiation through glazing. Temperatures as high as 35°C to 40°C have been recorded within the internal workspace, and research has proved that this can result in a loss of concentration, leading to a downturn in productivity.

In the 1970s the application of solar glass rose in popularity, which was a natural means of reducing the level of heat and light entering a building. One of the fundamental problems though with such glass was that it reduced light levels all of the time, regardless of whether it was a sunny or overcast day. This would create gloomy internal environments, which could only be rectified by switching the lights on. However, this had two negative results. Firstly it is widely accepted that the use of natural light is better for occupants than artificial lighting and, secondly, energy consumption would rise.

In a typical office today we still experience similar problems. If the sun comes out, the internal blinds go down and the lights go on. Of course the temperature is often then controlled through the application of air conditioning equipment, but clearly this impacts negatively on energy usage. Depending, for example, on the size of the building and number of staff within it, the energy needed to power an air conditioning system, even only during the hot summer months, can be significant.

Even with the blinds down, however, heat still enters the internal space and a gloomy atmosphere is created. The power of the external heat often goes unrecognised, but it is hugely significant for building design. On an average office floor, depending on activity, 150 lux to 300 lux will be created from internal sources. The sun alone however, on a bright day, can create 1 million lux and, even when overcast, 1000 lux. Therefore reducing heat load from the sun to the internal space, but optimising natural light levels, can decrease the need for air conditioning and artificial lighting, and with it consequential increased energy usage. This is where the combined application of solar architecture products, such as solar shading louvres and daylighting systems, as well as natural ventilation, come to the fore. It also meets the principles of Approved Document L2, where the emphasis is placed not simply on reducing temperatures, but on decreasing the heat load within a building and better protecting the environment through the application of low energy designs.

In many commercial projects today, be it an office, hospital or leisure building, there is an increasing trend to design with larger glazed areas. This has a positive psychological effect, but leads to a correspondingly high transfer of energy through the facade, in both summer and winter. The ideal scenario for architects to achieve is to maximise light energy transfer, avoid use of artificial lighting, (which is expensive, produces CO2 and extra heat), and to minimise heat energy transfer. A further complication to consider is avoidance of glare, especially on computer screens.

Consequently solar shading and natural ventilation systems are being specified on an ever increasing scale for the numerous benefits they provide: reduced air conditioning and artificial lighting loads, freedom from glare, protection from the external environment, view to the outside, visual impact and, of course, compliance with Approved Document L2. Aside from L2, which recommends the use of passive cooling measures such as solar shading, there is also the Workplace (display screen equipment) Regulations 1992 to consider. This requires areas with such equipment to have windows with a suitable system of adjustable covering to attenuate the daylight that falls on the work station.

In order to design and determine the performance of any solar shading system it is necessary to calculate the position of the sun, the intensity of its rays and, ideally, the effect these will have on heat loads and temperatures within the building. This is a complex process and there are many points to consider which include seasonal requirements, daily weather, solar altitude, solar azimuth, vertical shadow angle, horizontal shadow angle and solar intensity. Once all of these points have been considered, and the necessary calculations made, the most appropriate solar shading system can be designed to meet the specific requirements of the building.

Typically there is a compromise to achieve between minimisng heat gain and glare and maximising daylight entry, which can lead to the specification of fixed or controllable solar shading systems. Depending on the geometry of the building fixed devices can meet the design specification, however, controllable systems can track the path of the sun providing the required shading throughout the day, at any time of year.

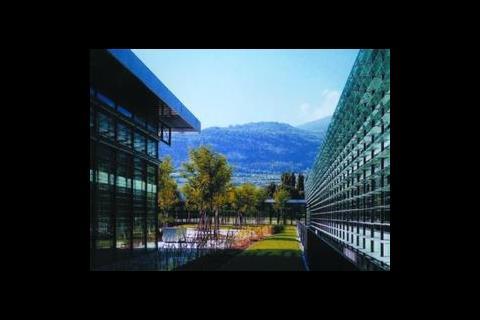

A recent example is a hospital in Switzerland designed with a controllable solar shading system. A central element of the design for the striking new Suva rehabilitation hospital, located in the Swiss canton of Valais, was that views of the surrounding mountains would be maximised, and summer heat gains kept to a minimum.

In Valais there are great differences in temperature between day and night, in summer and winter, and the building had to be able to respond to these changing weather conditions. A tinted glass louvre system was used, spanning some 3 400 m2. The automated system responds effectively to changes in the weather. The function of the glass louvre is to regulate the internal temperature of the hospital, protecting it from the variable external conditions. However, the louvre has also enhanced the visual impact of the building, which has been achieved in dynamic fashion: as the louvre moves up and down the 'mood' of the facade changes.

Clearly the combined application of solar architecture and natural ventilation products provides many benefits, and can help ensure compliance with Approved Document L2. Occupants benefit through having a comfortable and airy internal space, and the building has less of an impact on the environment. For a number of year's countries across Europe have embraced such concepts, but only a minority of building services engineers here have a full working knowledge of such schemes. However, designed early into a project product, installation, commissioning and lifetime running costs can be reduced.

Source

Building Sustainable Design

Postscript

Robert Buck is product marketing manager, Colt International.

No comments yet