Sean Affleck, one of the architects who left Norman Foster’s practice to join Ken Shuttleworth at Make, tells Andy Pearson why he thinks glass facades have had their day

And we’re off. In less time than it takes to pull a pen from my jacket pocket, Sean Affleck has greeted me, shaken my hand and started an animated description of the disc-like cladding system on which architect Make is working.

Sketches of one of the architects’ current schemes hang above a bright red sofa tucked against the wall of the practice’s jumbled London office. The sofa is flanked by several rows of elevated benches where, between the clutter of sketches and cardboard models, most of practice’s architects are busy at work.

Affleck, oblivious to them, is enthusiastically extolling the simplicity and flexibility of the cladding’s aluminium framing system. “This is a hot spot,” explains the 42-year old architect, sweeping his hand over the sketch of a corner building that will have maximum exposure to the sun. “In this area, the cladding will have more solid discs to limit solar gains,” he enthuses, before setting off on a tour of the schemes adorning the workshop’s perimeter wall.

Dressed in a collarless shirt with his hair pulled back into a ponytail, Affleck looks the aesthete, but he knows a thing or two about cladding; the last project he worked on before leaving Foster & Partners to join Ken Shuttleworth at Make was the spheroidal City Hall for London’s mayor. Every one of the building’s 660 triangular cladding panels that form the building’s faceted facade was a different dimension and had to be constructed using state-of-the-art manufacturing techniques.

And, to ensure he keeps abreast of future developments in this area, he is also a board member of industry body The Centre for Window and Cladding Technology. “The biggest impact on the way the building looks and feels and works is the facade,” he explains.

Make’s playful facades, with their profusion of colour and geometric expression, differentiate the practice’s schemes from the more reserved designs of architects such as Shuttleworth’s former business partner Norman Foster. “Ken [Shuttleworth] has said the all-glass building is a symbol of the eighties,” says Affleck. He denies this is Shuttleworth having a dig at Foster and his trademark transparent buildings, although his smile hints otherwise. Instead, he says by way of explanation: “We believe an all-glass building ignores the need for insulation in winter and cooling in summer; if you add solid areas then more sustainable servicing solutions become possible, such as the use of chilled beams and borehole cooling.”

Right on cue, Affleck’s whistle-stop tour of the office stops opposite a computer-rendered image of Grosvenor Waterside tacked to the wall. This is a residential scheme for 264 affordable and private apartments, built in two blocks with predominantly solid walls and strategically located glazing.

The hierarchy of window shapes and sizes relates to the functions behind: large recessed balconies with floor-to-ceiling glazing ensure living spaces are bright and airy, while slender vertical and horizontal glazing slots create a more private space for the bedrooms. “We carved openings where the glazing will be most effective,” Affleck explains.

Getting the balance right

He is not, however, so naive as to suggest all buildings should have solid facades: “If you solve one issue, such as heat loss, by using a nice solid wall to keep a building warm in winter and cool in summer, then you’ve created another issue by increasing the number of lights that need to be on all the time – so you’ve shot yourself in the foot”.

To save their feet, the designers at Make work with consultant Gordon Ingram Associates to inform daylight design. “What Ingrams will be doing, right from the earliest sketches, is assessing the impact of the cladding design on light levels 5 m and 10 m away from the facade so that we can make decisions based on fact to minimise the number of lights needed,” he explains.

Continuing his tour, Affleck explains how the design of a building’s facade evolves from the outset. “As designers, we talk about mass; we talk about bulk and about whether the site should have a vertical expression or horizontal expression; we consider what the materials should be and we also start thinking about whether it will be a unitised cladding system or a stick-system – all these are considered right at the early stages of a design”. He says the facade design goes through “loads of different iterations,” each assessed on factors such as cost, thermal performance and buildability. Cladding contractors and consultants, too, are brought in early to advise how a solution might be made to work.

Circumnavigation of the office complete, Affleck makes a beeline for a second room. Here, groups of people are seated around tables in earnest discussion. He clears a pile of sketches from a vacant table and warms to his theme of the need for the early involvement of the entire design team in a project. “Everything is much more sophisticated now; you can’t consider packages like the services as bolt-ons, you need the engineers involved in order to make informed decisions right at the beginning process,” he explains.

The concept of an integrated team is given additional impetus with the latest revisions to Part L and the Greater London’s Authority’s requirement for buildings to generate 10% of their energy requirement using renewable technology. “If you want to get your building through planning, you have to start to think holistically to address these issues; it’s the responsible way to build,” he says, banging his hand on the table for emphasis. He maintains that by considering the design holistically it is possible to meet the renewables requirement. “We know it’s viable: we’ve done a London project with 14% energy demand from renewables.”

He cites an office scheme where Make is involved in the third phase of a project (but wasn’t involved in the earlier phases) as further proof of the impact of energy regulations. These buildings, which were completed two years ago, had fully glazed facades, fan coil units, air-conditioning and electric underfloor heating. Through intelligent design, for example by placing the windows only where they are needed, Make has designed the building so that it does not need air-conditioning. “We are using the building’s concrete mass to keep it cool, which saved a lump of money that could pay for a more expensive cladding system,” Affleck explains. As a bonus, since the heating load is less, the engineer can now use borehole cooling. “We find that the services engineers we deal with, firms like Roger Preston and Atelier 10, are fully aware of all these issues.”

In Leeds, Make is designing a 20-storey residential tower with a wind turbine on the roof. The architect approached wind turbine manufacturers who advised a 20 m diameter turbine “as high as you can get it,” and designed the building with a 20 m diameter vertical axis at the top of the building. This will provide power for all the general areas in the tower “five times over,” which should give a payback of five years. “It throws up all sorts of wonderful issues such as pigeons being sucked into the turbine, vibration, or what happens to any bits that break off,” he observes. As a result, Make is working with various universities to look at the viability of these systems.

Affleck says sustainability is fundamental not only to Make’s designs, but to the way the practice works. “If we’re serious about sustainability we have to do it right the way through the business,” he says. As a result, the environmental organisation Future Forest has assessed the business’s CO2 emissions. This has led to a policy to minimise travel, which in turn resulted in an site office being set up in Edinburgh, staffed with locally recruited people: “to ensure people are not flying up to Edinburgh all the time,” as Affleck explains. Make has also opened an office in Birmingham for the same reason. “And if we have to fly to Hong Kong, we plant trees somewhere to compensate,” he says.

This approach to sustainability is particularly impressive for a practice that is less than two years old. Ken Shuttleworth set up Make architects in January 2004, after he had resigned from Fosters. It was not long before he was joined by some of his old colleagues. “There were four of us who could not resist joining him,” says Affleck. They established Make as a trust – similar to the set-up at retailer John Lewis. “The view was that to design a building is not a one-person job, it’s a team effort, so the whole team from top to bottom should share in the success of the company,” explains Affleck. Every year, the profits are shared.

It’s a formula that appears to be working. Since setting up in January last year, the firm has grown – and grown. “We’re now up to 60-odd people and we’ve moved office five times,” he laughs, clearly revelling in the creative environment this egalitarian way of working has created.

My visit at an end, Affleck returns to his computer. I turn to say a last farewell. Too late: Affleck is already engrossed in his latest project.

King’s Reach

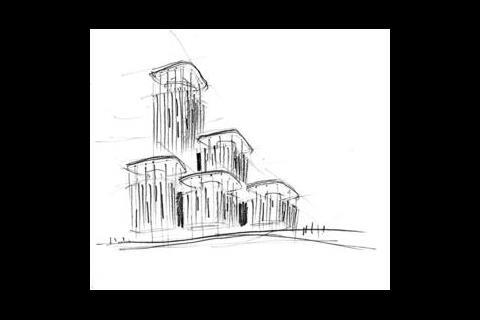

This is a Richard Seifert-designed 30-floor, 1960s office tower with adjacent low-rise office and residential blocks by the River Thames in Southwark, London. According to architect Sean Affleck, the building was at the end of its useful life: it had narrow, inefficient floor plates and was haemorrhaging energy.

Make has taken a sustainable approach to redeveloping of the site. The team was against wasteful demolition, instead investigating how to recycle the building.

Consulting engineers Hilson Moran modelled the wind flow around the tower, proving that natural ventilation could be used – a decision that turned the drawback of narrow floor plates into a strength. Make responded by wrapping the concrete structure of the tower in insulated cladding fins and perforated panels that conceal an opening vent controlled by the BEMS. The structural fins also shade the glazing and give the building renewed presence in this unremarkable area of London. The thermal mass of the newly exposed concrete soffits will allow chilled beams to be installed, completing the building’s rebirth.

Four additional floors will be added to the building, while the low-rise offices will be replaced by a cluster of smaller 6–12 storey towers. The redevelopment will increase the office accommodation by 100%, turning the building from a liability into an asset.

Hampstead Road

For this project, Make is working with RHWL Architects to provide an office and a warehouse, just north of London’s Euston Station. The office comprises two accommodation fingers, joined by an atrium. Cladding for both buildings takes the form of interlocking L-shaped anodised aluminium panels. The panels are finished in light gold hues on the offices and silver on the warehouse, while the glazing will be body tinted to reduce glare and solar heat gain and provide privacy.

Grosvenor Waterside

This is a scheme for 264 private apartments, in two blocks angled in a “V” shape to maximise views of the River Thames. The building has echoes of traditional warehouse vernacular, but its facade is distinctly modern as the hierarchy of window sizes and shapes relates to the functions behind. Large recessed balconies with floor-to-ceiling glazing ensure the living spaces are bright and airy, while slender vertical and horizontal glazing slots create a more private space for the bedrooms. The “champagne” colour of the anodised aluminium cladding panels was chosen to harmonise with a listed pumping station on the site.

Source

Building Sustainable Design

No comments yet