Two landmark buildings have joined the manhattan skyline. one is LEED Gold, the other isn’t rated at all, but which is the greener, and can they make a dent in the city’s energy-guzzling reputation, asks Will Jones

- Both opening in 2007 the New York Times Building and Hearst Building are the latest landmarks on New York’s skyline. Both claim to be the city’s greenest building.

- The Hearst uses an indoor waterfall to humidify the atrium air; the NYT has a garden at its centre and a gigantic skylight over the news room.

- Comparison of design and services types including key ventilation and day lighting strategies.

- The Hearst is New York’s first tower certified LEED Gold. The NYT isn’t rated because its architect didn’t want to be constrained by box-ticking exercises.

Standing on the 42nd floor of the New York Times Building in Manhattan, I look out on the pulsating neon lights of Broadway, an endless carbon-monoxide-belching parade of yellow cabs and innumerable roofs sporting industrial-sized chunks of plant. This metropolis, like London, Tokyo, Singapore and now Dubai and Abu Dhabi, is consuming almost unfathomable amounts of energy and any attempt to change the trend could seem futile. But change it must, and the US building services engineer Flack + Kurtz, part of the WSP Group, is at the cutting edge with its work on the New York Times Building, opened in November, and the one-year-old Hearst Building.

Environmental aspirations

Each building lays claim to being New York’s greenest skyscraper. The Hearst Building was the first tower in the city to attain a LEED gold rating: 90% of the steel used in its construction contains recycled material; it uses 26% less energy than a tower built to standard building codes; rainwater collection reduces the amount dumped into the sewers by 25%; and so the stats go on.

The New York Times Building has a co-generation plant that supplies 40% of the power for the Times company’s offices; its advanced dimmable lighting system produces energy savings of 30%; and there is even a garden, with birch trees, in the midst of this corporate colossus. But the Times has no LEED rating: the architect, Renzo Piano, stated that he wanted to create a building that would first benefit the people using it, before ticking environmental boxes.

“LEED accreditation is sought for different reasons, from an overriding environmental concern to corporate bragging rights,” says Gary Pomerantz, executive vice-president of Flack + Kurtz. “We were just as committed to designing environmentally on both buildings and both clients were pushing for an energy-efficient building because each is an owner-occupier and so will be paying the bills. ”

So, which is the greener tower – and what difference do they make in a city filled with gas-guzzling giants? Read on.

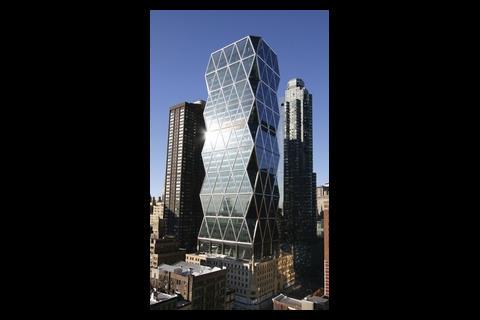

The Hearst Building

The faceted glass and steel of the Hearst Building rises from the top of the original six-storey stone-clad structure, built in 1928. From this historic base, architect Foster and Partners designed a 46-storey tower reaching 182m. Internally, there are two distinct zones: seven-storey atrium, which features horizontal skylight system spanning between the historic facade and the new, slimmer tower, and the office floors.

The internal environment of the atrium space is controlled via a number of techniques. The most immediately evident of these is Icefall, a three-storey sculpted water cascade that circulates filtered rain water, cooling the space in the summer and humidifying it in the winter. “The waterfall plays an important part in regulating the environment within the atrium space,” Pomerantz says. “The water is normally free-cooled in a 14,000-gallon tank on the roof, but in especially hot periods a plate-frame heat exchanger can be used to chill it to about 18ºC to lower the atrium temperature.” The recycling of rain water also saves 1.7 million gallons annually that would normally be run-off storm water.

The air quality and temperature in the atrium space is controlled using a minimum of mechanical plant. Radiant underfloor heating is used during winter on all floor levels of the atrium. For most of the year, cool air is drawn in from outside at low level and extracted at the highest point in the atrium. In summer, when the temperature at the ceiling can reach 32ºC, this hot air is dumped outside and spill air from the office floors is recycled to condition the space. This technique saves energy as the spill air is already cooled to 21ºC, as opposed to 32ºC, via central systems located on the 10th and 30th floors, thus reducing cooling requirements.

“There is much more outdoor air used in this building than others in the city,” says Pomerantz. “Some 75%, as opposed to an average of 15%. It is filtered to minimum efficiency reporting value (MERV) 13, which gives 95% efficiency, while typical applications operate to MERV 8. And, when we do need to condition the air mechanically, high-efficiency chillers and fan motors again reduce our energy consumption compared with other buildings.”

The office floors operate on a conventional overhead heating/cooling VAV system. Low solar gain glazing has been installed to all levels of the building and daylight sensors control the artificial lighting throughout.

However, one of the most important elements of the efficient design and construction of the Hearst Building was not a new piece of kit or innovative passive design. “Independent commissioning was the key to ensuring this building operates at its most efficient,” says Pomerantz. “External verification, by a firm not involved with the build, is a luxury in the US. It costs money and often folks think, ‘Best not let the fox look after the chickens’. But, in doing it, we established a baseline, a marker that the building was performing to from day one. Now, subsequent testing shows if adjustments need to be made to ensure that the Hearst Building continues to run at its most efficient.”

The New York Times Building

While the Hearst Building could be described as bold, even brash, the New York Times Building is as understated and refined as a 52-storey tower can be. Its glazed facade is see-through rather than mirrored – low iron content glazing was used – and the extensive brise-soleil consists of 186,000 delicate ceramic rods in a pale off-white. The facade has not been without problems, however, with surrounding pavements closed because of ice falling from the rods, and reports that windows have cracked.

The rods are the most noticeable products of a remarkable design process set up to create the most comfortable working environment possible within an office tower. Renzo Piano worked with Flack + Kurtz, the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the Times building management team to build a full-scale model of the southwest corner of the building’s 19th floor in a car park in Queens. This 400m2 testing ground was fitted with more than 100 sensors to monitor the environment as the team refined methods to maximise daylighting while maintaining internal comfort.

“Daylighting is inherent in the design,” says Glenn Hughes, managing director of construction for the New York Times. “The experimentation found optimum light levels achievable for working and produced a definition for light and glare that enabled the consultants to create radiance studies for all parts of the building at all times of the year. This modelling made the building feel the way it does today.”

It feels very comfortable. The floors are bright and airy, even on a rain-soaked winter’s day. Some of the daylight-controlled artificial lighting is on but only towards the centre of the large floor plates. Heating and cooling to the entire building is provided by an underfloor plenum system from central heating/cooling plant, allowing conditioned air to be pumped gently into the office spaces, rather than pushing it down from the ceiling at high velocity. Warm air is extracted through ceiling vents.

The building also uses free-air cooling, with air from outside being brought inside on cool days. Waste heat from the 1.4mW gas-powered co-generation plant is used to heat the space on colder days and provide cooling via hot water for the 275-ton absorption chiller for the for the rest of the year.

Perhaps the most impressive part of the Times’s environmental strategy is its ongoing monitoring and maintenance. “We have designed bespoke equipment to monitor constantly the conditions within the building,” Hughes says. “This ensures that we are continually able vigorously to test the environment and maintain the high levels to which the building has been designed.”

Hughes and his team have two trolleys, or carts as they call them, designed by the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab to monitor light and environmental quality. The first is a glorified light meter with nine sensors connected to a PC and an advanced digital camera system to record glare on the facade. The trolley has its own power source, so Hughes can tour the building taking readings anywhere he chooses. Data from these tours influences changes to the automated blind system and artificial lighting. Hughes is now lowering the lighting slightly on some floors to save energy.

The second trolley has an extendable mast with temperature sensors set at different heights. It measures the average occupied zone temperature (AOZT). “That’s from 4ins above the floor to 67ins high,” Hughes says. “We feel that if we maintain a comfortable temperature in this zone, everyone will be happy. What happens outside of it is immaterial.” Data from the AOZT trolley is used to adjust the underfloor heating system, in conjunction with an array of monitors in the plenum, which detect airflow rates and hot spots.

“These gizmos might seem a little over the top,” Hughes says, “but by keeping the building running to its optimum, we are ensuring the most efficient use of energy, keeping our employees happy and operating to the best of our ability at all times. The carts will soon pay for themselves.”

Which is the greenest?

The New York Times and Hearst buildings are just two environmentally conscious towers in a forest of voracious, vertigo-inducing monsters. Which is the most sustainable is debatable. “They are similarly environmentally friendly and I couldn’t choose which would be more sustainable,” Gary Pomerantz says with a smile. His practice, Flack + Kurtz, acted as services engineer on both. “Each has its own attributes: the Hearst’s central systems mean that more outside air is used, while the Times’s co-gen plant makes it especially energy efficient. I’d have to say that, all things considered, the two buildings are equally sustainable.

“However, in these energy-constrained times, with oil at $100 a barrel, we should be required to design buildings to be energy efficient. Currently, environmental accreditation comes at a premium. People say they’d love to do it but they haven’t got the money. In the future, the government agencies need to get involved and change the building codes to force people to build more environmentally friendly or mandate that all projects meet a certain LEED standard.”

As high-profile examples of the direction in which all significant urban architecture should be aiming, the Hearst Building and the New York Times Building both present innovations, attributes and ideas that designers can adopt as they aspire to build ever more environmentally consciously in the world’s greatest cities. It’s just a pity that the impact of these two towers, with their very different personalities, is minuscule compared with the negative impact of the energy-hungry monoliths surrounding them.

Project teams

Hearst Building

Architect: Foster and Partners

M&E consultant: Flack + Kurtz

Structural consultant: Cantor Seinuk Group

Lighting: George Sexton Associates

Development manager: Tishman Speyer Properties

Associate architect: Adamson Associates

New York Times Building

Architect: Renzo Piano Building Workshop

M&E consultant: Flack + Kurtz

Construction manager: AMEC

Cost consultant and project manager: Gardiner Theobald

Associate architect: FXFOWLE

Source

Building Sustainable Design

Postscript

To see video footage of the building click here:

http://link.brightcove.com/services/link/bcpid1243698085/bclid1258439103/bctid1333282196

http://link.brightcove.com/services/link/bcpid1243698085/bclid1258439103/bctid1334428532

Original print headline: "New York Giants" (Building Services Journal, February 2008)

No comments yet