The green benches are restored, but an opportunity to reform the way Parliament works for post-war Britain is missed

Charles Barry’s original mid-Victorian House of Commons chamber became one of the most high-profile casualties of the Blitz when it was destroyed in May 1941. Its reconstruction after the war would be an opportunity to modernise Britain’s parliamentary system for a post-war world. As the report below shows, this opportunity was largely missed.

Published the month after the definitive end of World War Two following the surrender of Japan, it quotes a speech given by Adrian Scott, younger brother of the lead architect appointed to the reconstruction of the chamber, Giles Scott.

The younger Scott explains why the committee overseeing the job had decided not to correct various antiquated quirks of the chamber inherited from the Victorian era. Its number of seats would remain 437, despite there being 640 MPs, there would be no public broadcasting, and members would still need to queue up in lobbies to vote instead of it being done automatically, a time-consuming practice which still irritates many MPs to this day.

News piece in The Builder, 7 September 1945

A TALK BY MR ADRIAN GILBERT SCOTT

ON Thursday afternoon, August 30, MR. ADRIAN GILBERT SCOTT, M.C., F.R.I.B.A., lecturing before the Town and Country Planning Association at 28, King-street, W.C.2, described the work in connection with the rebuilding of part of the House of Commons. The Rt. Hon. Sir Arthur Salter, M.P., presided.

Introducing the lecturer, the Chairman said that Sir Giles Scott would have been present but was out of London. Westminster was the chief centre of Parliamentary democracy in the world, because American democracy was Presidential democracy as distinct from Parliamentary democracy. Everyone who had worked in an assembly like the House of Commons was conscious that the traditions and character of that assembly depended to a great extent on the building in which it met, and he had been relieved to learn that the instructions of the Select Committee were that the character of the building should be preserved. In an oblong chamber with the dimensions kept small, and the Opposition facing the Government, you could feel you were dealing directly with the Member or Minister you were answering, and it was of the utmost importance to the proper working of Parliament that this kind of debate should not be replaced by one more like the speeches of an electoral broadcast.

The LECTURER, reviewing the history of the House of Commons, said that for the last four hundred years its Members had sat in a series of rectangular chambers. He quoted from a speech made by Mr. Winston Churchill to the Architectural Association in 1924: “We make our buildings, and afterwards they make us; they regulate the course of our lives. The whole character of British Parliamentary institutions depends upon the fact that the House of Commons is an oblong and not a semi-circular structure. The Party system undoubtedly depends upon the shape of the House of Commons, so that when you are called upon to build council chambers for legislative bodies, be very careful to bear in mind the immense responsibility. You may do more in the layout of the chamber to affect the history of your country than if you were spending your time in framing the clauses of the Constitution itself.”

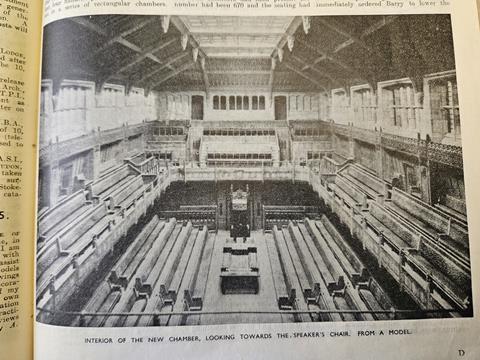

Bound up with history, said Mr. Scott, was tradition and procedure, this being the carrying out of a system evolved through many years of trial and error. For instance, the actual seating of the Chamber had undergone many alterations since its building a hundred years ago, when the cross benches behind the bar had been occupied by peers. The new seating provided for 437 Members as before, but the seating for strangers had been increased by 67 to 326, that for reporters by 58 to 161, and that for officials by 2 to 15. The old close spacing for strangers’ seats had been retained, the slogan “numbers before comfort” carrying the day. There had been a great deal of discussion about the provision of only 437 seats for the 640 Members, but when the Irish Members had been present the number had been 670 and the seating had proved sufficient. There were seats enough except on a very few special occasions. As regards the style of architecture to be adopted, the Select Committee decided that the 10 per cent. to be rebuilt should be in late Gothic to blend with the rest of the building; but within this limitation the architects were left free.

Mr. Scott continued: “The first consideration was how to enlarge the Chamber itself above the Gallery level to accommodate the extra strangers and reporters, and it was decided to enlarge the North Gallery for the reporters, to match an enlarged South Gallery for the strangers, and also to add a third row of seating to the side galleries. Incidentally, this replanning entailed moving the whole Chamber some five feet northwards. It was also decided to retain the stone screens at each end, at the level of the side windows, so as to preserve the horizontal band of stonework which was a good feature of the old design. After this the ceiling was entirely redesigned, together with the windows and the panelling generally, with the carved ornament definitely concentrated in broad horizontal bands instead of being scattered over the whole surface as before, the character being in general much more domestic and less ecclesiastical than previously. Barry’s original Chamber had a high coffered ceiling, as in the House of Lords, but I understand the Commons never held a sitting in this, as after an apparently hilarious visit to it when first completed, they felt so lost in it after fifteen years’ use of a thirty feet high Chamber that they immediately ordered Barry to lower the ceiling. Pugin died that year, and Barry rather ingeniously lowered the ceiling by springing it from the transomes of his high traceried windows, which thus became dummies and only showed from the outside; but with no Pugin to help, the new ceiling was of rather poor design and detail.

“The Select Committee also asked for the maximum of additional accommodation adjoining the Chamber to be provided for Members and officials. Fortunately, there was a space nearly 30 feet high beneath the old Chamber and Division Lobbies, consisting of heavy brick vaults provided by Barry for Dr. Reid’s elaborate ventilation scheme, which never materialised. This space we are dividing into two floors, thus providing nearly 20,000 square feet of new accommodation for Members. Much of this will have to be artificially lit and air-conditioned, as in modern hotels. Again, above the Chamber and Commons Lobby we have been able to provide another 10,000 square feet of new accommodation for officials without breaking the skyline of the Palace; while the adoption of a steel frame, with thinner walls, and the omission of some inadequate light-wells, has enabled certain offices and the accommodation for reporters to be nearly doubled in area.

“The floor levels proved to be very complicated, as although Barry insisted on his principal floor being kept at one level throughout the eight acres of Palace, all the other floors in the six wings abutting on to our new work were at varying levels and all had to be linked to our new building.”

The number of staircases was to be accounted for by the necessity of strictly segregating Members, strangers and reporters The reporters’ requirements had involved free access to seats without disturbance of anyone else, and elaborate telephone arrangements; and they were now getting accommodation they had been in need of for years. As it was impossible to construct a chamber of this size and shape and guarantee it acoustically perfect, it had been decided to install sound amplification, and under the auspices of the B.B.C. 456 loudspeakers were being installed. No provision was made either for public broadcasting or television, but every other known device was being installed, including annunciators, division bells, electric clocks, pneumatic tubes and vacuum cleaning, in addition to heating and air-conditioning for every room and telephone box. Thus the building was developing into a mass of ducts and conduits, all of which had to be discreetly hidden.

Mr. Scott continued: “The Palace was reputed to stand on a vast 10 ft. thick concrete raft, but a series of borings disclosed that each wing (but not the courtyards) was carried on a 6-ft. raft of lime concrete, resting on sand and gravel some 16 ft. above blue clay, with a constant water level unaffected by the river tides some 4 ft. below the bottom of the raft. This raft has proved satisfactory, and as our new building, with its thinner walls, will weigh less than the old, we are retaining it, with modifications to suit the new point loads

“The south and east sides of the old medieval cloisters were entirely destroyed by an H.E. bomb, and the north and west sides badly shaken, but the Ancient Monuments Branch of the Ministry of Works has undertaken the repair of these latter, while we rebuild the remainder. These two-storeyed cloisters, built in the sixteenth century with elaborate fan vaulting, were badly damaged in the fire of 1834 and practically rebuilt by Barry and Pugin to the old design.

“The Commons Lobby south of the Chamber will have to be entirely rebuilt, and as this formed an integral part of the Palace, balancing the Peers’ Lobby, it was decided to rebuild this generally to the old design, but with more refined detail and a less cumbersome wood ceiling. This will enable the so-called ‘Churchill Arch’, namely, the archway between the Commons Lobby and the House, to be reinstated in its calcined condition.

“A scheme of ventilation had been prepared by Dr. Oscar Faber and is now being incorporated in the building. The chief problem is not the heating of the building but its cooling and the elimination of hot air.”

This remark provoked a laugh. Mr. Scott continued that unlike a theatre the number of people to be provided for in the Commons was liable to sudden violent fluctuations without notice. The ventilation must follow the Members to the division lobbies, and to enable this to be done, it was proposed to install a periscope in the Chamber ceiling, so that the control engineer might observe any large movements of members or strangers and adjust the ventilation accordingly. Each occupant of the Chamber would be provided with a heating panel under his feet and a gentle current of air from varying directions around his head, the air being introduced horizontally above head level and extracted mainly at the ceiling. Air conditioning with humidification and cleaning by electrical filtration was being installed.

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS.

Questions followed. One was as to visibility. Mr. Scott said that everybody got a clear view of the despatch box where Ministers stood when answering questions. The reporters also got a much better view.

Asked as to the use of the floor beneath the Chamber, Mr. Scott said there would be no catering there. There was to be a lounge with seats for interviews with constituents and separate rooms for secretaries and those who wanted privacy.

The CHAIRMAN said these two things were current needs. At present the Member interviewed by a constituent stood in a corridor with everybody passing by.

The shape of the Chamber coming under discussion, the chairman said that by planning for conflict we had avoided national disunity. The Continental system of having all seated in a semicircle, with various groups merging into one another, was intended to unite people, but it resulted in the splitting up into a number of parties.

Broadcasting was another matter that came under discussion. The chairman said it would be fatal if every Member, when speaking, thought of what would be the effect upon his constituents. Speeches in Parliament would become like those on a political broadcast. The effect of a deliberative assembly would be destroyed.

In reply to a further question he said broadcasting might be desirable on a few great occasions, subject to a vote of the House.

A method of automatic voting being suggested, the chairman said there was no technical difficulty, but it was felt that it would increase the number of purely discipline divisions. Going into the lobby was not altogether a waste of time, because it gave an opportunity which would not otherwise occur for a Member to get hold of a Minister and impress something upon him.

In reply to a question about lighting Mr. Scott said the new House would be better lighted, both naturally and artificially, than the old. The lighting would not be fluorescent in the Chamber though it might be in the rooms below. The objection to fluorescent lighting was that it flickered when first put on.

As to the new method of electrical air conditioning, it had been introduced from America, and this was the first occasion of its use on a large scale in this country. In reply to questions about the stone used, Mr. Scott said this was Clipsham stone from Rutland. The stone originally used in the House of Commons had been selected by eminent geologists, but any practical stonemason would have known that it was unsuitable for London conditions. Clipsham stone had been proved in London. He did not know its analysis.

Questions as to how long the work would take were answered by Mr. Bontt to the effect that with super-priority it might be done in three years. But priority was no use: it must be top priority. Without this the work might occupy five years or even seven.

Mr. F. J. OSBORN, on behalf of the audience, thanked the lecturer for his talk.

More from the archives:

>> Nelson’s Column runs out of money, 1843-44

>> The clearance of London’s worst slum, 1843-46

>> The construction of the Palace of Westminster, 1847

>> Benjamin Disraeli’s proposal to hang architects, 1847

>> The Crystal Palace’s leaking roof, 1851

>> Cleaning up the Great Stink, 1858

>> Setbacks on the world’s first underground railway, 1860

>> The opening of Clifton Suspension Bridge, 1864

>> Replacing Old Smithfield Market, 1864-68

>> Alternative designs for Manchester Town Hall, 1868

>> The construction of the Forth Bridge, 1873-90

>> The demolition of Northumberland House, 1874

>> Dodging falling bricks at the Natural History Museum construction site, 1876

>> An alternative proposal for Tower Bridge, 1878

>> The Tay Bridge disaster, 1879

>> Building in Bombay, 1879 - 1892

>> Cologne Cathedral’s topping out ceremony, 1880

>> Britain’s dim view of the Eiffel Tower, 1886-89

>> First proposals for the Glasgow Subway, 1887

>> The construction of Westminster Cathedral, 1895-1902

>> Westminster’s unbuilt gothic skyscraper 1904

>> The great San Francisco earthquake, 1906

>> The construction of New York’s Woolworth Building, 1911-13

>> The First World War breaks out, 1914

>> The Great War drags on, 1915-16

>> London’s first air raids, 1918

>> The Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building, 1930

>> The Daily Express Building, 1932

>> Outbreak of the Second World War, 1939

>> Britain celebrates victory in Europe, 1945

>> How buildings were affected by the atomic bombs dropped on Japan, 1946

No comments yet