A year ago, the nuclear new-build programme seemed like construction’s best hope of recovery. But since then, major players have withdrawn and concerns over electricity market reform have led to growing fears of delay, or even cancellation. Vern Pitt looks at where we are now

Last May, Dr Mike Weightman, the UK’s chief inspector of nuclear installations, published his initial report into the prospects for the UK’s nuclear future, and the industry breathed a sigh of relief. Weightman had been asked to examine the role of existing and new nuclear power plants in the UK in the wake of the Fukushima disaster in Japan, and had given it an outline stamp of approval.

It meant the construction industry now had all the pieces in place to gear up for a nuclear new-build programme which had investors, political and public support and now safety approval.

But a year later, one of the three projects in the pipeline is up for sale, the remaining investors are increasingly nervous about the prospects for returns and, while political backing in the UK remains solid, support abroad is waning and impacting on the UK programme.

So concerned are the MPs on the House of Commons energy and climate change committee that last month they launched an in-depth inquiry into the UK’s nuclear future. The initial signals are not good. Tim Yeo, Conservative MP and chair of the committee, said after the first evidence session: “I’m no longer at all confident that we will have a significant replacement for our nuclear power in the next 10 years.”

Any delay or cancellation of the programme will be a huge blow to the construction sector, which contracted by 4% in the last quarter. Much depends on nuclear over the next four years: the Construction Products Association predicts that construction growth in the electricity sector will far outstrip growth in all other areas of the industry - driven primarily by the nuclear programme. It predicts it will nearly triple by 2016, compared with 2011 levels, and continue at that high level for a decade or more.

But can already stretched construction firms afford to invest in upskilling their staff and preparing for a programme which now appears in doubt, no matter how big the rewards?

Mind the gap

The UK is heading for an energy gap. By the end of this decade, the country will have lost 20% of its current generating capacity.

There is, however, some debate over how much of this will need to be replaced. The Association for the Conservation of Energy argues in its “Corruption of Governance?” report that the gap can be plugged not only by new capacity but by energy-efficiency measures.

Although much of that would provide stimulus for the construction industry - buildings are responsible for a third of our energy use - it would not be at the same scale as the major civil engineering projects that the nuclear programme would provide.

The government argues that electricity use is likely to rise as a proportion of our energy as transport becomes more electrified and heating switches from gas to electricity. Any prediction is inherently vague at this stage, given the timescales and number of variables, but the government appears set on a cautious path to provide new-generation supply rather than risk a gap.

For the construction industry there will be a boost whatever type of generation ends up coming out on top, argues Alastair Smith, chair of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers’ power division. “The investment in nuclear skills is worthwhile because the next thing that will come along will be gas-fired power stations [to replace base load or provide quick-firing proof generation] and while the quality required will not be as high as nuclear, having those skills will certainly help convince people to give you the contract,” he says.

Financial concerns

The adage often attached to the business case for nuclear power plants by those in the industry is: “Only two things matter, the cost of capital and the capital cost.”

While the capital cost is fairly predictable - EDF says it will cost around £10bn to build its first two UK reactors at Hinkley Point in Somerset - the cost of capital is wildly unpredictable as the eurozone crisis rocks lending markets. Small percentage point changes make a big difference to the viability of loans this size.

In April, credit ratings agency Moody’s issued a veiled warning that firms progressing with nuclear power plants were putting their ratings at risk, when it praised E.ON and RWE’s abandonment of its UK nuclear plans (see below). Plus, in April EDF’s partner Centrica, which owns British Gas, threatened to pull the plug on its stake in the development of new reactors which would leave EDF in need of around £2bn for its two reactors at Hinkley Point and more still for its plans for Sizewell in Suffolk. Maja Zeremski, director of thermo-power generation at consultant Davis Langdon, says: “Centrica is in quite a tricky position: its market capitalisation is in the order of £16bn - how can it contribute a 20% stake to £25bn projects?”

Only the use of government-backed borrowing, which can be done at much lower interest rates, could substantially reduce the cost of capital. But this is highly unlikely because of its political sensitivity and the strain it would place on the government’s ferociously protected triple A rating.

Clouds over the Horizon

The biggest blow to confidence in the sector has been the sale of Horizon Nuclear Power by its German owners RWE and E.ON, announced at the end of March.

It means that construction firms that make the investment to win work on the first nuclear plants, being built by EDF, can no longer be sure that, if they aren’t successful, a second pipeline is just around the corner. It could be years before that opportunity materialises.

While insider sources maintain that a sale can be completed by “late summer”, others remain sceptical. Nigel Adcock, managing director for nuclear at consultant Sweett Group, says: “Whatever programme Horizon had with regards to first worker on site will have gone back from that date.”

But Scott Parker, director of energy at consultant WSP, believes the situation is recoverable: “If [a buyer] came in and made their [reactor] technology decision very quickly they could probably get back on track. It could be a small delay. Once the sale is completed they could potentially move very quickly because everything is in place to get going.”

But that technology choice could have a significant impact on the timescale as well. Westinghouse, which is bidding in partnership with contractor Laing O’Rourke to build the plant, put its application for safety approval through the Generic Design Assessment (GDA) of its AP-1000 reactor on hold last year because it did not have a buyer. That puts the timescale for the AP-1000’s deployment behind competitor Areva, which has been bidding in partnership with contractor Balfour Beatty for Horizon’s proposed plant at Wylfa in Anglesey. Areva hopes to have GDA approval by the end of this year.

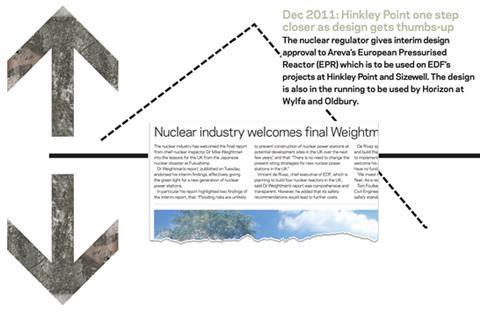

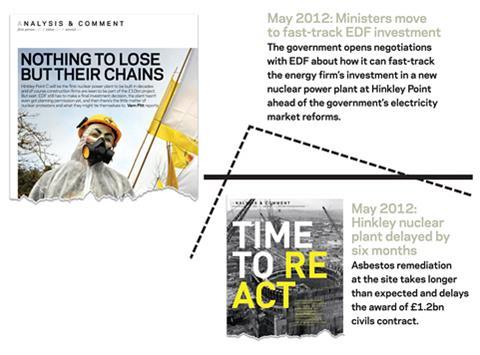

NUCLEAR’S CHANGING FORTUNES

The Hollande factor

Now questions are also being raised over the future of French state-owned EDF’s commitment in the wake of the election of president François Hollande. Hollande had promised to cut France’s nuclear power by about a third if he won, but that promise was made as an olive branch to France’s green party, who went on to do very badly in the election.

In the immediate wake of his election, some commentators feared there might be a delay to EDF’s programme while a re-assessment of its priorities was undertaken. But a few weeks on, Hollande’s rhetoric of investment and growth inspires greater confidence. Adcock says: “[This is] one of the big projects which is going to have a big benefit for French industry as well as British.”

Nor is the troubled progress of EDF’s current European projects at Flamanville in France and Okiluoto in Finland, both of which are over time and budget to the tune of more than €2bn, necessarily a bad thing. Some in the industry argue this makes the successful completion of its next new-build project, Hinkley Point, even more crucial - because EDF and Areva need to demonstrate that their reactor design, the European Pressurised Reactor (EPR), can be delivered to time and cost to win work elsewhere in the world.

Are we ready?

Nobody has built a nuclear power plant in the UK for nearly 20 years, so some skills have understandably withered. This begs the question of how prepared the industry is to take on a project of this scale.

“The one thing the supply chain has been fairly poor at is the audit trail of the materials it provides,” says Smith. “If you’re putting tarmac on a road, no one really needs to know where the stone came from - but you will need to for a nuclear power station.” Indeed, the problems at EDF’s project in Flamanville have been linked to quality of concrete not being high enough.

Smith argues that upskilling the workforce rapidly enough to meet these standards will be a challenge. He sees a particular gap in mechanical engineering where he says the industry currently struggles to get the high-calibre staff needed - though he adds that their role tends to come later in the project so there is time to tackle this before the programme is fully under way.

Parker, however, is much more relaxed. He notes that the civil engineering required accounts for only 1-2% of the UK’s capacity and therefore there will be plenty of resources.

Smith points out that these resources are likely to be pooled into bigger firms. Nuclear contracts, even in the second and third tier of the supply chain, are often large and long term, and therefore financially stable firms with a large capacity to throw at the projects may be at an advantage. “You can see the merging of subcontractors together to be larger and more influential. Companies that are fit for merger are likely to get snapped up,” Smith says.

Questions for the House

Last week, the government published its draft Energy Bill containing proposed reforms to the electricity market. Among the plans is a structure of guarantees - called “contracts for difference” - for the prices that those wishing to build new electricity generation will be paid for decades to come. The plan is to de-risk technologies with a large upfront capital cost for investors.

But although the proposals were welcomed as a step forward by most, they do raise questions. “What will the strike price be and what’s the certainty of the counter-parties to the contracts?” asks Alan Thompson, director of EMEA energy at Arup.

Energy companies are understood to be keen to have a robust counter-party in place to guarantee they will get paid. Speaking at the energy select committee, Volker Beckers, chief executive of RWE, said that government backing was “crucial”.

But the government doesn’t want to do this itself. Instead the proposals will have the contracts signed by the National Grid - raising questions over whether this will be secure enough for investors.

Plus the government will not agree a price for the electricity from new plants until late next year. “My concern is that this will result in further project delays because company boards will not make decisions until the reforms are in place,” says WSP’s Parker.

The government is already in discussion with EDF about an early contract for difference before the system is implemented in 2014, and it is inviting applications from other potential investors.

But the whole system is subject to a legal challenge at the European Commission by protest group Energy Fair. Gerry Wolff, leader of the group, says: “The proposed ‘contracts for difference’ is a blank cheque to a nuclear industry that is already heavily subsidised.”

Energy Fair’s complaint centres on the argument that guaranteeing returns to particular generating technologies, including nuclear, doesn’t meet with European competition rules.

Although the government is still in discussions with the Commission to ensure its system is permissible, it is not clear when this will be fully resolved.

No comments yet