One of Britain’s oldest contractors went bust last week, but not because of a problem contract, and not because it had an empty order book. The truth was altogether stranger

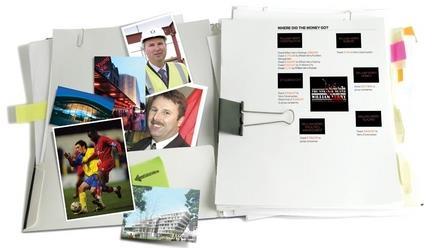

It was last Wednesday that John Gibson, the chairman of Verry Construction, admitted that the rumours spreading through the industry over the previous few days were true: the 177-year-old contractor, which had twice been behind buildings on the Stirling prize shortlist, was on the brink of administration.

The Hertfordshire-based mogul posted the following message on the website of St Albans City football club: “As many fans may be aware, Verry Construction is about to go into administration. This should not affect the football club, which is owned by the holding company, William Verry Holdings Limited. The two companies are not linked as far as the football club is concerned.”

But the football club and the contractor were more entwined than Gibson would have the 350 supporters of the Conference South team believe. As the 120 staff and subcontractors of Verry Construction work out what the firm’s demise means for them, Building can reveal that when Verry Construction went under it was owed millions of pounds by four other firms in the Gibson empire – including more than £500,000 by the football club.

The fact that Verry Construction was lending money to Gibson’s other businesses while on the brink of collapse led to a furious row at the top of the company. This became so bitter that Gibson banished Craig Jones, Verry Construction’s chief executive, from the firm’s Isle of Dogs headquarters in February. Jones was to spend the next two months watching from the sidelines as the firm’s cash flow problems went from critical to fatal.

The missing cash

A look at the last accounts of the seven companies under the William Verry Holdings umbrella, dated 30 June 2008, shows that when Verry Construction went under it was owed £2.6m by four of them; St Albans City’s debt was £515,147.

In addition to the football club, William Verry (Facilities Management), which went into administration last Friday, owed the construction business £170,348 and William Verry (Glazing Systems) owed £418,337.

A statement in the accounts of Verry Glazing shows a marked lack of urgency for the sum to be repaid. It said: “Of the company’s liabilities, £418,337 is owed to a group company which has agreed not to press for payment for more than 12 months.”

The final piece of the £2.6m puzzle can be found in the latest accounts of residential development business William Verry (Europe), which owed Verry Construction £1.4m. There is no mention of any repayments in the latter’s accounts.

Intra-group debt is not abnormal and there is no evidence that calling in the sums would have averted the collapse of the £100m-turnover firm. However, its last stated debt position, on 30 June 2008, was £5.9m, and this would have been cut in half.

Jan Crosby, a construction accounting expert at KPMG, said such intra-group debt was fine while turnover was rising but could be a problem in a downturn. He said: “The contracting model brings in cash that can be used in the window between when you are paid and when you pay your subcontractors. In a rising market that’s fine, but when cash stops coming in you need to be able to get the money back quickly. If not, you’ll have problems paying your supply chain.”

A source at Verry Construction put it more colourfully. “What happened was that the tide went out and the construction business was caught with no clothes on.”

The problems the company had in paying its supply chain were well documented. Before it filed for administration, it faced a series of winding-up orders from creditors, and last month Gibson said he had appointed Roy Willor as operations director to sort out the pay rows.

But there is no suggestion that one particular problem job contributed to the firm’s collapse, as is often the case with contractors. Although the firm is rumoured to have lost a seven-figure sum on the Young Vic theatre in London (one of the Stirling nominees) after what one industry source called “an aggressively priced bid”, it is understood there were no schemes that were problematic enough to push it under. The Young Vic was completed in October 2006.

An operations source within Verry also rejected claims the company had bitten off more than it could chew with its Building Schools for the Future work, which included large jobs in Hackney and Kent. They said: “The company never spent too much on bidding, and it operated in consortium with larger companies. Verry enabled the big boys to play the regional card when bidding.”

Its order book was also healthy and stood at more than £300m earlier this year.

A look at the accounts of the companies in the group shows that when Verry Construction went under, it was owed £2.6m by four of them; St Albans City’s debt was £515,147

Trouble at the top

Whatever the exact cause of the cash flow problems, the fact the supply chain was waiting to be paid exacerbated growing tensions between Jones and Gibson. The Verry source said Jones was “extremely concerned and seriously irritated” when subcontractors were left out of pocket.

According to Companies House, Jones is still a director of the company but it is understood that the rift over the use of company money eventually became so deep that in February Gibson told his chief executive to stay at home. The source said: “It was clear that there was a disagreement over the way John was pushing money around the business and that led to the falling out.”

However, Jones declined to comment, Gibson was unavailable for comment and the phone line to the company’s head office was dead last Friday.

The source added: “Craig was fuming. I don’t think he could believe all this money was going out of the construction arm at a time when the market was going into recession.” Further evidence of the rift may be indicated by the fact that Jones did not sign off the company’s 2008 accounts. Neither is there a chief executive’s statement in the document, which was signed by Gibson.

Construction is a far cry from Jones’ previous role as managing director of electronics giant Philips in the UK. Before joining Verry in July 2005, he was credited with turning around Philips’ fortunes in Britain, boosting market share from 7% to 13% and increasing turnover from €300m to €650m (£266m to £577m) in six years.

Those who know him in construction circles describe him as an urbane, straight-talking and compassionate character who is genuinely concerned about the fate of Verry. Clive Perceval, managing director of Shepherd Construction’s southern division, said: “I’ve got a lot of time for Craig. He’s a genuinely nice chap who has endeavoured to steer Verry through its difficulties in the best way he can while keeping the focus on client relationships.”

Although the two men are said to have had a good relationship before the row broke out, Gibson, a Geordie by birth, has a different character to his chief executive.

Those who know him say he is fiercely loyal to his friends and family and protective of his personal interests. He is well-known in his home town of St Albans and one local said: “He likes being the big cheese around here. There’s a picture of him with the Queen on the wall in his local pub that has run in the local paper.”

However, a regular at St Albans’ home games said he was not so popular on the terraces, although chants of “Gibson out” that rang from the terraces earlier in the season have now died down.

They said: “He’s turned up to about two games since Christmas, which doesn’t go down well. There’s also a feeling that the club isn’t really going anywhere and the stadium could do with a lick of paint and a tidy up.”

Was Jones set to return?

Despite not having been at his desk since February, one source familiar with the administration process has told Building that Jones mounted an eleventh-hour rescue bid for the company, in which he has a double-digit stake, after it became public that it was headed for administration.

The precise details of which parts of the business Jones wanted are unclear but it is understood to have delayed the company’s fall into administration this week. As Building went to press, Essex-based McLaren Construction had been confirmed as the company in the frame to buy the firm.

Despite the sale, the fate of Jones, Gibson and Verry looks likely to remain unclear for some time. Construction industry sources that know Jones say he is “weighing up all options”, including whether he has any legal recourse after being sidelined in February.

Although both men have refused to break their silence about the row, it seems there could be still more chapters to be written in the strange story of the demise of William Verry.

Postscript

Original print headline: The William Verry files

2 Readers' comments