The US architect’s visual arts centre has joined an inglorious list of public projects that have paid a high price for lofty ambitions. As the local council desperately searches for funding to complete the stalled project, Thomas Lane finds out what went wrong

Welcome to another tale of a building designed by a big-name architect and funded by a cash-strapped public body that goes horribly wrong. Other episodes in this series have included Bath Spa, the building that was meant to take the town back to its origins in an exotic cloud of steam, but ended up £33m over budget and five years late. Then there was the Clissold Leisure Centre in east London, Hackney council’s attempt to brighten up Britain’s most deprived borough. The initial budget of £7m rose to an eyewatering £45m, and the scheme opened properly eight years late. The last example, the Public, was meant to distract the residents of West Bromwich from their worries with a Will Alsop fantasy world of pink blobs. This has only just opened, a mere three years late and £13m over budget.

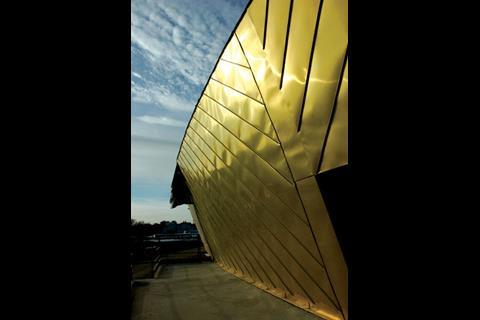

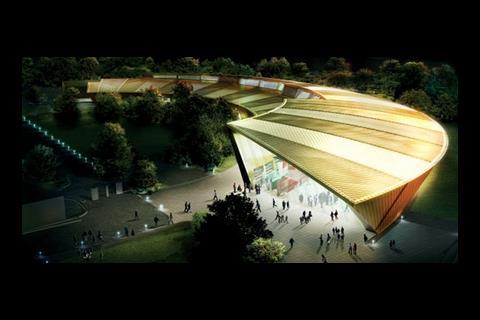

Now these projects are over, there is another building ready to fill the gap. It has all the right credentials – it was designed by Rafael Viñoly and it is a bright gold-coloured semi-circle intended to transform a particularly grim bit of Colchester with arts-led regeneration and, true to form, virtually nothing has been done to the visual arts facility, as it is called, since the end of last year. Technical problems have swallowed up the original budget and the form of contract between Colchester council, the client, and Banner Holdings, the contractor, means the council is liable for any cost overruns – but the pot is empty and nobody is stepping forward to refill it. Here is the story of the latest, unfortunate victim of what is increasingly looking like another triumph of hope over experience.

For a start, the building is fiendishly complex. The walls forming the inner and outer edge of the semi-circle lean outwards, and the angle progressively changes from almost vertical at the east end to seriously slanted at the west, where the entrance is. The distance between the inner and outer walls varies, too; the building is wider at its entrance. This is intended to add dynamism to the visitors’ experience. The tricky geometry extends to the roof, which is not content with a simple curve; it has a vertical step that will be glazed to allow light deep into the building. A building like this needs a grand entrance, so the roof extends over it as a dramatic cantilever, and the entrance itself will be glazed. Access is needed for large works of art, but the architect decided a simple sliding door round the back would not do. Instead, a 10m wide, 3.5m section of the glass facade will open like a glorified garage door.

The vision is great … if the cash is there to realise it. The original budget was £16.5m, with the money coming from a range of organisations including the Arts Council, the East England Development Agency and Essex council. Only £1.5m came from Colchester council. But the money problems began almost as soon as the project did. The first problem was construction inflation. Planning issues delayed work so construction inflation pushed up costs by £1.3m to £17.8m. Then a fundraising shortfall of £700,000 meant the original funders were approached for another £2m at the end of last year. Unfortunately, that entailed Colchester council signing an agreement not to ask the funders for any more money.

Then work began on site, and more things went wrong. The leading edge of the cantilever over the entrance drooped in the middle because the steel beam inside the building that supported it twisted under the loads more than anticipated. This appeared to have been caused by the sheer complexity of the beast. “The design required a straight edge but it needed to be much tighter than the codes required to achieve it,” says Albert Taylor, a partner at structural engineer Adams Kara Taylor. The answer was to add additional steelwork to the structure inside the building near the entrance.

The drooping cantilever may have been fixed, but according to specialists working on the building, the roof has deflected in other places by up to 200mm. “It’s out all over the place,” says George Richardson, proprietor of cladding specialist Richardson Roofing. “We raised this but were told to press on.” Richardson says his job was made particularly difficult because the architect insisted that the standing seams on the roof and walls match exactly. According to Richardson the deflections made this “impossible”.

He says the architect maintained that it could be done because the CAD models said so. “It’s all very well for the architect to draw this as a nice computer model but you never get the building exactly as you designed it,” says Richardson. John Drew, principal of Rafael Viñoly Architects in the UK, concedes that the job was not straightforward. “It’s a complicated building. Wrapping something straight around something curved is obviously difficult.”

The only way Richardson could deliver what Viñoly wanted was to make each section of wall cladding separately so that each seam matched the roof. Inevitably this cost more. Richardson was working to a letter of intent that allowed a value of £2.1m for the work. Once this was reached, Richardson was quite within his rights to ask for more money, or to stop work. With no more money on the table he left the site at the end of 2007.

I’m not going to knock it down because we will have to repay funders £14m. There is total commitment to get it finished

Martin Hunt, Colchester Council

Richardson says he has done what he could, including handing £75,000 back to the client for work on the roof, which he describes as “a grey area”. He also sealed the joint between the roof and cladding free of charge. He adds that he is happy to return on an open-book, cost-plus basis. “Nobody is getting rich out of this, but nobody wants to be fleeced,” says Richardson.

Since Richardson pulled out, costs have continued to rise. Expensive scaffolding has been sitting idle for six months, the euro has got stronger against the pound and metal prices have gone up.

At least the cladding specialist is prepared to return. The same cannot be said for the glazing contractor. The glazing for the clerestory windows on the roof, the facades and the big opening door were to be done by Eiffel. When it turned up, the glass for the roof wouldn’t fit because of the deflections. A source close to the project said Banner Holdings and Eiffel could not agree a price so Eiffel would not be coming back. A second specialist was found but went bust.

Banner is under no illusions about the task it is facing. “It’s very complex and large, which makes it tricky from an engineering point of view,” says Peter Elston, Banner Holdings’ managing director. He is reticent about whether Banner has found another glazing specialist, describing it as “commercially sensitive at the moment”.

Where does this leave the job? Rafael Viñoly Architects has largely washed its hands of the problems, saying it’s down to contractual issues between the council and contractor. These two are holding a meeting on 29 July to try to thrash out a solution.

The local press has suggested that £3.5m is needed to finish the building. Martin Hunt, the council’s deputy leader, will not say how much he thinks it will cost, but says it will not be cheap. If no agreement is reached, the council is going to hand the decision over to local residents. The choices are: bail it out with more cash, mothball it or knock it down – the last option is particularly unpalatable to Hunt. “I’m not going to knock it down because we will have to repay the funders their £14m. There is absolute, total commitment on all sides to get this finished.”

But the fickle nature of local democracy coupled with the controversy surrounding the project may mean the Colchester saga could end up at the top of the hall of infamous projects that went badly wrong.

Three others that went wrong

1/ Clissold Leisure Centre, east London, designed by Stephen Hodder Associates

£38m over budget and eight years late

2/ Bath Spa, Bath, designed by Sir Nicholas Grimshaw

£33m over budget and five years late

3/ The Public, West Bromwich, designed by Will Alsop

£13m over budget and three years late

Postscript

Original print headline 'How Viñoly’s Colchester arts facility lost its shine'

3 Readers' comments