At the peak of its construction 3000 labourers toiled on site, climbing 300 feet above the Thames sans hard hats and harnesses. The building's two million feet of scaffolding would, it was claimed, have stretched from London to Edinburgh.

Less celebrated but no less amazing were the engineering services. They weren't only advanced, they were seminal: radiant heating and cooling ceiling panels, double-glazed windows with mid-pane blinds and river cooling for the air conditioning.

Forty years on, a massive masterplan for the site presents the perfect opportunity to reappraise the Shell Centre's contribution to building design. What engineering lessons can it teach today's engineers? More important, did it work? Over the next 10 pages, we tell the story of a building way ahead of its time.

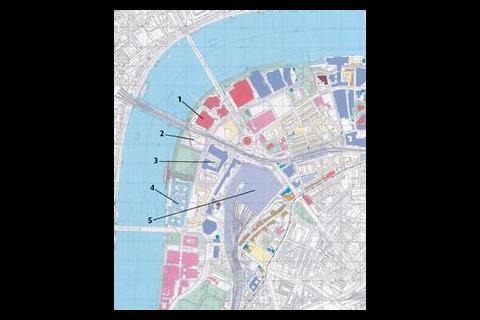

Seven years ago, an informal group of London businesses clubbed together to draw up a regeneration plan for London's South Bank, a massive tract of land extending from Westminster Bridge to Blackfriars Bridge.

Prompted in part by the opening of Waterloo International – the much heralded "gateway to Europe", but also by the blight created by decades of bad urban planning, the regeneration plan sought to create a new identity for the South Bank. Out would go the hostile and bleak 1960s infrastructure, and in its place would come a flourishing centre for culture, business and entertainment within a "cohesive residential community".

In 1999, the businesses, now the 18-strong South Bank Employers' Group, commissioned Lifschutz Davidson to assemble an urban design strategy that pulled together the 40-odd redevelopment projects proposed for the South Bank.

The report, which was issued for public consultation in Spring 2000, includes the 'South Bank Masterplan' by Rick Mather Architects for the South Bank Centre. This is expected to go for detailed planning permission in mid-2001, which a view to work starting in mid-2002.

At the heart of the masterplan lies Shell International's redevelopment proposals for its Shell Centre upstream building. With the staff facilities in the two-storey basement no longer needed, Shell is planning to use the space for commercial, entertainment and retail use.

Early ideas involve the creation of a covered public mall leading from an extended Jubilee Gardens to Waterloo Station. The ground and basement levels of the 26-storey Shell Centre complex would become home to a multiplex cinema, a health and fitness club and a range of cultural and entertainment facilities (see above).

The redevelopment of Shell's basement will be integrated into the masterplan, with a common landscaping strategy and co-ordinated strategies for transport, servicing and retailing. Funding is expected from the National Lottery, private donations and capital contributions from commercial office building on the site.

If the planning and land holding issues can be resolved, the £150 million basement complex could be open in three years.

Downloads

Early ideas for the Shell Centre redevelopment

Other, Size 0 kbEarly ideas for the Shell Centre redevelopment.

Other, Size 0 kb

Source

Building Sustainable Design