Seventeen days. A 500-acre site. £8.3bn worth of construction. The 2012 Olympics will make over a corner of east London with sports arenas, an athletes’ village and all the other buildings needed to host a major international sporting event. In the process, speculators from Hackney homeowners to large-scale landowners stand to make a killing out of the regeneration activity. But these are the short-term gains. The bigger question is whether the Olympics can have a lasting impact on regeneration, not only in the Lower Lea Valley, but further afield – and whether all of the change will be for the better.

Lower Lea Valley

Ground zero for the Olympics is the Lower Lea Valley. The regeneration of the area, which has recently seen the bulk of its traditional industries follow the nearby dockyards into the history books, has been on the drawing board ever since the late 1990s when it was grandly dubbed the “Arc of Opportunity” by Newham council. But the intervening years have seen little activity – a situation that critics say has been exacerbated in the past two years by the uncertainty hanging over the area in the run-up to the Olympics decision.

Chris Brown, development manager of insurer Morley’s Igloo Regeneration Fund, believes that the valley didn’t need the Olympics, pointing to the transformation that has already taken place in neighbouring areas over the past two decades “That was going to happen, Games or no Games; the political will to regenerate east London has been pretty strong.”

But Anthony Dunnett, former chief executive of the South East of England Development Agency, is in no doubt that the Games are the necessary catalyst for the valley’s regeneration. “Without the Olympics, it would have taken two generations to develop this part of Lea Valley.

It can happen in 10 years with the help of the Olympics.”

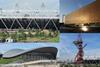

The most visible of the Games’ legacies will be the sports facilities, including the main stadium, an aquatic centre with Olympic swimming pool and three smaller arenas. The Games planners say these will act as anchor projects for the area long after the Olympic flame has been doused – although some sceptics point out that as highly irregular generators of economic activity, stadiums and regeneration don’t mix.

Affordable and key-worker homes

Within the Games precinct itself, the London 2012 bid document states that the Olympic Village’s homes will be designed so that they can be converted into affordable and key-worker housing once the Games are over. The Games masterplan says 9000 homes will be delivered around the Olympic Park, set to be London’s largest park, the edge of which will be defined by residential development.

The Olympic decision will also kickstart the regeneration of the valley’s southern end, where the London Development Agency owns a number of key sites and an estimated 13,000 homes are proposed. Mark Bottomley, partner at architect BPTW, says developers and landowners are already falling over themselves to commission feasibility studies, prompted by the increase in land values triggered by 6 July’s announcement.

They will be working to a document, due to be published in the autumn, outlining the mix and nature of development in the area. This will provide a framework for the London Thames Gateway Urban Development Corporation when it takes over responsibility for determining major planning applications in the area later this year.

Architect Paul Latham of The Regeneration Partnership, which is involved in designing a number of projects in the area, predicts that this framework will substantially loosen the rigid land use policies that have kept many of the valley’s ex-industrial sites preserved in aspic. Peter Minoletti, major sites manager for Newham council, says the planning framework will not result in a wholesale sacrifice of employment sites for housing, partly because some of those businesses displaced from the Olympic precinct will need new premises. Local councils are keen to encourage the transformation of the valley into London’s Left Bank, a hub for creative businesses in the East End.

The addition of two stations along the south-of-Stratford stretch of the North London Line rail link, which is being converted to the more frequent Docklands Light Railway, and faster services to the city centre on the Channel Tunnel Rail Link mean the area will be able to cope with a much higher density of development. The Greater London Authority is keen to avoid this opportunity being squandered in a rash of low-quality, speculative development, and so developers could come under pressure to rethink existing schemes.

As well as high-density accommodation, planners are keen to see a mix of housing types in the valley, including family homes in quieter residential enclaves. The fate of Ballymore’s plans for up to 3000 flats on the former Pura Foods factory site at the southernmost tip of the valley, where council and GLA planners are keen to see a greater proportion of three and four-bedroom homes, will lay down a marker for the valley’s development.

Winners and losers

Winner Newham mayor Sir Robin Wales, who will see long-term regeneration plans finally realised

Losers The businesses that will be forced to relocate from the Olympic site to enable its redevelopment

Surrounding Area

Hackney’s “Murder Mile” is within walking distance of the Olympic Games site – a graphic reminder, if one is needed, of the deep-seated social and economic problems faced by the area. Turning around the fortunes of such neighbourhoods is the main Olympic prize that the area’s authorities are interested in. People will want to show off more than normal. The Olympics give developers an incentive to deliver

Ken Dytor, Urban Catalyst

The Games have already had a tangible impact on the private housing market in Stratford, where the bulk of homes on the market at the time of the Olympics announcement have already been snapped up. Countryside Properties chairman Alan Cherry says: “In our projects in east London, the level of inquiries is noticeably picking up from the weekend after the announcement, despite the bombings of 7 and 21 July.”

Keith Barnett, a director at local estate agent Strettons, expects the main impact on the housing market to be felt within a 15-20 minute walking distance of the Games site. A further spur for the local property market will come from those firms displaced from the precinct but reluctant to move away from their established workforce.

Property markets in the surrounding area will particularly benefit from improvements to the area’s infrastructure linked to the Games, such as the long-awaited Tube extension of the East London Line to Dalston and the Olympic Park, which will provide much-needed public green space in a heavily built-up area.

Urban Catalyst director Ken Dytor thinks the key impact of the Games will be on the quality of the development that comes forward, which will be spurred in turn by higher land values. “People will want to be showing off rather more than they would otherwise do. The Olympics will give developers an incentive to provide the best quality, most sustainable buildings that they can deliver for the price.”

Local authorities too are keen to present their areas in the best light to the thousands of sports fans who will be passing through en route to the Games. Hackney regeneration supremo Guy Nicholson says his authority is keen to launch a major drive to clean up the borough’s grot spots before 2012. And local boroughs are hoping that the London Thames Gateway Urban Development Corporation will fund a feasibility study into removing unsightly overhead power cables from the whole of the Lower Lea Valley, not just the Olympics site itself. That desire to impress will extend to the quality of new development in the area.

A downside for housing associations is that increased land values will make it harder for them to build in an area that has long been a source of relatively inexpensive sites. At least one developer has already pulled out of a deal with an association following the Olympic decision. But the impact of rising land values is likely to be cushioned by the extra housing that will be generated under Section 106 deals.

Winners and losers

Winner Silvertown Quays developer David Taylor, who will see demand for his scheme soar

Losers Housing associations, which will find it increasingly difficult to compete for sites as land values rise

Rest of london

In terms of London as a whole, the economic impact of the Olympics is likely to be relatively modest. “It’s a lot of money, but it has to be put in the context of London’s economy,” says Anthony Vigor, who carried out a recent report into the impact of the Games for the Institute of Public Policy and Research think tank. Although the Games’ £4.7bn budget sounds a lot, it is being spread across seven years, equating to about 2% of the capital’s annual GDP.Savills head of residential research Richard Donnell believes that the main Olympic effect on house prices will be confined to the areas bounded by the Lea, the A13 and the Hackney Marshes. But Ken Barrett of estate agent Strettons predicts that there will be a ripple effect across east London as would-be home hunters in the immediately surrounding area are pushed into neighbouring areas.

Professor Tony Travers of the London School of Economics hopes the regeneration of the Lower Lea Valley will heal the historic fracture between the traditional heart of the East End and the more recent suburbs. But he says he will be very surprised if the Olympics does not put negative pressure on regeneration projects in the rest of the capital, especially if Camelot’s National Lottery scratchcard game does not generate as much cash as its backers are hoping. The London Development Agency’s scarce human resources are already being concentrated on the area with officers working flat out on the project.

The Department of Trade and Industry has allocated £250m worth of extra money to the Games over the next seven years. The LDA insists that regeneration efforts in other parts of London will not suffer as a result of the focus on the Lower Lea Valley and that existing commitments will be honoured. London as a whole needs to ensure that it is presenting its best face to the world in July 2012, a source insists.

But working out the areas that have lost out will be hard, according to Travers, because we will never know where money would have otherwise been spent.

Winners and losers

The impact is going to be fairly concentrated geographically

Anthony Vigor

Winner Greewich-based architect BPTW, just one of the city’s architectural practices that will benefit from the interest stimulated by the Olympics

Losers Regeneration schemes in west London that will be out of sight and out of mind when the Olympics happens

Thames gateway

The Olympics could be the biggest marketing bonanza imaginable for the Thames Gateway. The organisers of the Sydney Games estimate that the free publicity generated by the event was worth AUS $2.4bn (£1bn) of advertising. In the UK, the seven years running up to the Games will see an intense focus on east London that should radically refashion the area’s image.

Authorities, agencies and developers operating in the Gateway are keen to ensure that the whole area gets its share of the Olympics spotlight. “People are already talking about what they can do on the back of the Olympic project,” says Countryside Properties chairman Alan Cherry, who is a board member of the Kent Thames-side delivery agency. Moves are already afoot to promote the Garden of England under a Kent 2012 banner. Commentators agree that the hype will increase developers’ interest in the area.

The infrastructure delivered by the Games will provide the missing ingredient needed to turn the Gateway into bricks and mortar reality, according to London Housing Federation policy officer Dino Patel. It will also focus development at the east London end of the Gateway where the infrastructure is most developed and brownfield sites are plentiful.

However, the downside for the Gateway is the danger of overheating in the construction industry that will make the skills shortage crisis sparked by the millennium look like small beer. The Olympics and associated projects will be sucking in scarce skilled labour just at a time when the Gateway already faces acute challenges attracting enough construction workers. “There are going to be issues in terms of training construction workers; we have to make sure that we’ve got the resources to meet that requirement,’’ says John Ladd, chief executive of British Urban Regeneration Association.

Stephen Jacobs, who is running the regeneration of Canning Town, is more sanguine. He argues that the Olympics provides a golden opportunity to train unemployed east Londoners who can then move on to work in the rest of the Gateway once the Games facilities are completed.

Winners and losers

Winners Construction workers

Losers Developers in peripheral, lower-value parts of the Gateway may well find it hard to keep pace with rising build costs

Uk

“The impact is going to be fairly concentrated geographically. It’s not to say that a company in the North-east won’t secure a contract, but the most critical impact will be felt in the East End of London,” says IPPR fellow Anthony Vigor. The only sporting event to be hosted outside of the capital will be the sailing in Dorset. The main dispersal of Olympics activity is likely to be the estimated 150 training camps that will be needed to train athletes, which could be sited anywhere up to 200 miles from London. And the construction industry, based as it is largely outside London, will benefit from the business generated by the Games.The downside is that concerns across London of regeneration activity being skewed by the Games will be writ large on a national scale. The prestige attached to the Olympics means that Whitehall will jump to attention if related projects need cash, which is likely to put pressure on budgets across government at a time when the Treasury has increasingly limited room for financial manoeuvre. Meanwhile, the Games’ financial reliance on the National Lottery means that there is inevitably going to be less cash available for the kinds of regeneration-related building projects funded from that source in recent years.

Winners and losers

Winner Construction companies that will land big contracts for the regeneration of the Lower Lea Valley

Losers Northern local authorities are likely to see cherished projects such as tram links put on the back burner

Downloads

Olympic Map

Other, Size 0 kb

Source

RegenerateLive

No comments yet