Inspired by the bowl skating of 1970s America, Folkestone’s multistorey skatepark – a world first – is set to transform the UK’s skating scene forever

Billionaire philanthropist Roger de Haan has bestowed his home town with many things: an art centre, a creative quarter, a regenerated harbour full of cafes and restaurants and a sports ground. Now in a world first, the former Saga holiday and insurance group owner’s charitable trust has gifted Folkestone the world’s first multistorey skatepark.

Skating is traditionally a fringe activity making use of street features such as steps, natural ramps, ledges and the like. Many councils have built dedicated facilities, but skaters have great affection for adopted spaces such as the undercroft at the Southbank Centre in London, said to be the birthplace of UK skating and where redevelopment plans were scrapped after vocal opposition. But why build a multistorey skate park – and what does it take to realise such an unusual scheme?

Externally, the multistorey skate park does not give much away, though it does invoke curiosity as to what it might be. Featuring narrow, rounded ends, the building tapers outwards towards the top and is cranked in the middle.

It is clad with perforated metal panels from the first floor up, which are interspersed with small, triangular areas of glazing. The ground floor is a mixture of concrete structure and glass curtain walling with a large concrete bowl hanging over the entrance. For the initiated, this hints at what lies inside.

The building’s name, F51, is derived from its location on a plot ringed by roads on the edge of the Creative Quarter next to one of Folkestone’s most deprived areas. According to Guy Hollaway, principal partner of architect Hollaway Studio, who has worked with de Haan on other projects, de Haan originally wanted a multistorey car park on the site to service the regenerated harbour area. But when he saw the drawings, he dismissed them as boring. Putting an existing skate park, which needed to be moved for a new housing scheme, on the roof was not enough to sway the client but sparked the idea of using the whole building for a skate park.

This project aligns with de Haan’s wider regeneration vision for Folkestone – including reversing the brain drain. “The whole idea of this project is to invest in young people,” explains Hollaway. “If you make young people’s lives fulfilling in education, sport and the arts, and make their town exciting, some of them will decide to stay in the town. That investment in that young person will come back 10 times.”

The cost of building the centre is a gift to Folkestone from the Roger de Haan Charitable Trust. Youngsters attending local schools will be able to use the centre for just £1 a month, with others paying more. The idea is that the skate park operation is funded by entrance fees.

Ambition

So, how does one set about designing a completely new building type? Hollaway says it was a case of “building invention” – working with de Haan over six months to come up with the idea, which includes incorporating a climbing wall and a boxing gym. This was followed by research including engaging with specialists in their field.

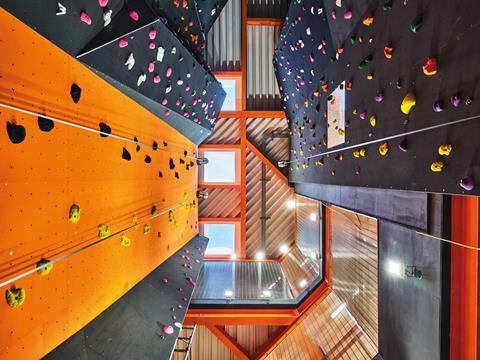

A firm called Maverick, which is run by skaters, specialises in the design and installation of sprayed concrete skate parks; another firm, Cambian Action Sports, does the same but with plywood. King Kong, a climbing wall specialist, was brought in to look after that side of the project.

“You are trying to put all these different people together and then extract the best things out of them to make something extraordinary, because that is the ambition of the project, and to try to be uncompromising in that ambition,” says Hollaway. “You need a pretty forward-thinking client who can trust and believe in what you are doing. That makes for a very unique client.”

Now we have got a facility locally that people will be proud to send their kids to to learn how to skate, whereas before it had that stigma

Alex Frost, marketing manager, F51

The building includes three skating floors catering to skill levels ranging from beginner up to expert, plus a ground-floor reception and cafe which will be decorated with skateboards. The boxing gym and changing rooms are on the ground floor and the 15m-high bouldering and climbing wall, the highest in the South-east, has more than 30 graded routes and spans the upper two floors. The skating floors will also be used for BMX and scooters, which will be available to hire for those who cannot afford their own.

The first floor is called “the bowl” and is for expert skaters. It features two large concrete bowls, one of which looks like an empty swimming pool with a strip of tiles below the overhanging concrete edge.

The likeness is no coincidence. Hollaway explains that so-called bowl skating originated from mid-1970s droughts in California. Swimming pools, which in California are bowl-shaped, were left empty to conserve water. Skaters saw the empty pools as providing the perfect skating challenge and so bowl skating was born. The second bowl is shallower and slighter easier than the pool.

The uppermost level, called “the flow floor”, features shallower bowls than the first floor. These are constructed from plywood. This floor also features quarter pipes and skateable pillars and is aimed at less advanced skaters.

Sandwiched in between these two floors is the street floor; as the name suggests, it includes features found on a typical street such as stairs, handrails, ledges and banks. The base of the floor is largely flat, ideal for budding skaters wanting to learn and hone their skills.

The street is all about being sociable and about tricks. This is the 21st‑century ballroom, where boy meets girl, and where you show off your tricks

Guy Hollaway, partner, Hollaway Studio

Hollaway sees this floor as a key social space. He says: “The street is all about being sociable and about tricks. This is the 21st-century ballroom, where boy meets girl, and where you show off your tricks.”

The unique nature of the building, coupled with unusual features such as the bowl floor – said to be the world’s only suspended example – meant it was a potentially risky project for a contractor to take on. Fittingly for a project that is about local regeneration, it has been built by the Folkestone-based contractor Jenner, which has worked with de Haan on other projects.

Given the risks, why did it take this particular job on? “It’s one of those opportunities that do not come along very often, and in my not short career it is the most interesting project that I have been involved with,” says Steve Restall, Jenner’s contracts manager.

“And it is very high-profile, certainly in the area and potentially nationally and internationally. So it was one of those which, as a company, we couldn’t let slip through our fingers.”

Jenner has done the job on a fixed-price contract for around £10m. The final account is yet to be determined.

Restall says that Jenner was responsible for a significant amount of the design, which was far more involved than would normally be expected for a job of this size. The most complex elements were the skate floors and the cladding, which had been designed before Jenner got involved. Jenner took on these specialists, integrating and co‑ordinating their designs into the main structure. Maverick and Cambian also delivered their portion of work under Jenner’s direction.

The building features a concrete frame up to first-floor level with shear walls and a lift shaft extending to the top of the building to provide lateral stability. The rest of the structure is steel with composite floors.

Ollie Wildman, director of buildings at structural engineer Ramboll, explains that there was a sewer on the south-eastern side so the first floor had to cantilever over this and support the structure above. “It’s doing all of that whilst being a skate floor with curvy concrete,” he says. “The analysis of that was very complex.”

Wildman adds that using precast concrete for the bowls or even prefabricated rebar for the structure was ruled out because the ethos of the project is to provide opportunities for locals.

To form the bowl floor a timber deck was fixed some 3m below the highest point of the floor which is the flat areas between the bowls. The deck is stepped so this is just below the high points but 3m below the base of the bowls.

The 3D model developed by Ramboll was used by Cordek to cut the shape of the bowl out of 254 large pieces of polystyrene formers, which were brought to site and assembled to form the bowl shape. The next step was to place the reinforcement – Restall says there “was a massive amount of reinforcement” in the bowls.

The complexity of this prompted Ramboll to create a tagging system to make it easier for the steelworkers to identify the correct piece of rebar for each location. Jenner’s specialist contractor Darby Groundworks sprayed the concrete to approximately 500mm deep, then Maverick applied a finish coat to create exactly the right shape and finish for skateboarding.

The two upper skating floors were built by Cambian over flat composite floors. These consist of frames up to 1.5m high, with the base of the bowl made from plywood. These were brought to site and assembled “like a giant 3D jigsaw puzzle”, according to Restall. The assembly is finished with a layer of 6mm thick ply which covers the joints between the frames and provides a super-smooth surface. This ply was laser-cut offsite and assembled with incredible precision – there are no gaps between the pieces.

Despite the unique nature of the bowls, Restall says this was not the most difficult part of the job. “By far and away the biggest challenge was the facade as it was completely bespoke,” he says.

The building is unheated and treated as outdoor space on the grounds that people are exercising vigorously so don’t need heating. The facade is made from anodised aluminium cassettes which are a perforated mesh externally and are solid on the inside. These need to be windproof and water-resistant as well as able to take the weight of an-out-of-control skateboarder or BMX rider crashing into the sides.

The cassettes are 5m long and 1.3m wide and had to be accredited for wind and water resistance as this is the first time a mesh facade has been used in this way. Testing was carried out at Vinci’s technology centre in Leighton Buzzard. Restall says waterproofing was the biggest challenge – it took two years to develop the system. The cassettes are suspended from the slabs with Halfen brackets and tied back to the slab below at the bottom. A neoprene seal was developed to stop water getting past the panels.

The technical challenges and the pandemic meant the project took longer than envisaged. The factory where the cladding panels were made in Spain was badly affected by the pandemic, which meant delivery of the panels was severely delayed.

Despite these challenges, the building opens in April with the hope that it will transform the skating scene forever. “It’s absolutely mind‑blowing, not just for Folkestone but for the national scene in general,” says Alex Frost, the centre’s events and marketing manager and a keen skater himself.

Skateboarding made its debut at the 2020 summer Olympics, with British skater Sky Brown taking the bronze for the women’s park event. Could F51 help push Britain up the Olympic rankings in the future? For Frost, the main benefit of the centre is making skateboarding socially acceptable. “Now we have got a facility locally that people will be proud to send their kids to to learn how to skate, whereas before it had that stigma,” he says. “It will help the general public take skateboarding more seriously which is huge.” And if Frost is proved right, building the next multistorey skatepark should be a breeze.

Project team

Client The Roger de Haan Charitable Trust

Architect Hollaway Studio

Structural engineer Ramboll

MEP and environmental engineer Atelier Ten

Contractor Jenner

Concrete bowl surface Maverick Skateparks

Timber bowl Cambian Action Sports

Cimbing wall King Kong

Concrete bowl and structure Darby Groundworks

Steel structure Metalfab Engineering

Facade engineering Fairhurst

Facade manufacture Imar

Facade installation Apex

No comments yet