LG has concentrated all its brain power in one campus. Spread over a million square metres in Seoul, the HOK-designed complex of laboratories, offices, atriums, parks and social spaces will host 25,000 researchers and engineers, to help the South Korean electronics firm edge ahead of the competition

South Korean electronics giant LG makes products for virtually every imaginable need inside and outside of the home. The list includes TVs, mobile phones, washing machines, fridges, computers, air conditioning systems and PV panels. The firm is also getting into new areas: self-driving cars, electric car motors and batteries, robots that deliver drinks to your armchair – the list goes on and on.

South Korean companies – LG, alongside its competitor Samsung and car manufacturer Hyundai – are grabbing an increasingly large share of the global market for consumer goods. Making headway in this fiercely competitive space requires energy, determination and plenty of investment, which they seem prepared for. For example, unlike many of their Western rivals, Samsung and LG develop products from scratch – both supply Apple with iPhone screens. In a bid to keep ahead of the game LG, has invested an eye-watering £2.7bn in a purpose-built research and development facility on the western edge of the capital Seoul, which – at one million square metres – ranks as one of the world’s largest. Already populated with 18,000 researchers and support staff, it will house 25,000 people in 26 buildings when the last phase completes in 2022. What’s even more extraordinary is that this huge, highly specialised development was built in just 33 months. It was designed by HOK, the architecture practice responsible for the Francis Crick Institute, the biomedical research lab near London’s St Pancras station that was completed in 2016.

“The spaces, inside and out, are designed to foster a culture where people can interact and form new ideas”

Larry Malcic, design principal, HOK

HOK has applied the same design principles used at the Crick to LG’s new facility. The former brings six research institutions together under one roof, with the idea that scientists will interact with each other and spark off new ideas – a principle called “collaborative science”. The complex in Seoul does this on a much bigger scale by aggregating eight different divisions – or “affiliates” in LG-speak – from around the country, into one location. “There is a limitation to growth with the current way of operating so we wanted to try a new approach,” explains LG’s Yongho Ha, a vice-president at the science park. “We needed to invest more in research and science in order to grow. The nature of R&D is changing and it is more efficient to converge science and technology. This will enable us to study more about artificial intelligence, software and communications. The purpose is to build the foundations for the future of the business.”

This was easier said than done. Each affiliate is run as a separate business with its own distinct research focus, identity and culture. HOK had to create a facility to satisfy these different divisions and promote the type of convergence LG wanted. To that end, the affiliates have their own buildings, but these are linked to the wider campus. “The design is all about encouraging people to get together,” say Larry Malcic, design principal for HOK’s London office. “The spaces, inside and out, are designed to foster a culture where people can interact and form new ideas.”

Making a change

Those involved with the project says the biggest challenge wasn’t designing and building the science park but managing cultural change. “The biggest challenge was getting agreement from such a multi-headed client,” says Malcic. According to Ha, each affiliate was involved in the design and specification of their buildings, but at times this didn’t align with LG’s vision of greater convergence, which required the firm hand of senior management. “The guiding principle was that this isn’t about the small picture but the big picture,” he explains. “If it’s a small loss for each affiliate but more productive for the whole group, then they [senior management] went in that direction.”

Inevitably there were compromises. The Crick features a large atrium with open balconies to foster a sense of openness and collaboration. Like the Crick, each building on LG’s science park features an atrium but these are closed off with glass screens. “We wanted to open it up, but it was a step too far for LG,” says Malcic. “Traditionally they have been sealed off.”

Within research areas the laboratories feature glass partitions, separated by corridors, to make them feel more inclusive.

Touring the campus

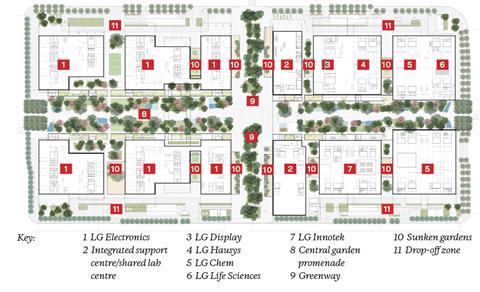

The science park comprises 20 buildings arranged on either side of a central boulevard, with a second, perpendicular boulevard creating a cruciform-shaped linear park, with water features, rock gardens, trees and seating areas.

The buildings are box-like and visually uncomplicated. Malcic says HOK adopted LG’s approach to product design, where all technology is encased within a no-frills box. “You spend the money on the inside and create a very simple package around it,” he explains.

Within each building the laboratories are arranged around a central atrium. The laboratories themselves are plain and business-like, with two permutations: “wet” and “dry”. The latter is used for computational research, while the former is designed for physical experiments to verify the results.

All the labs are designed to be reconfigured easily to accommodate changing needs. “The scientists don’t know what they will be researching next year, as technology is changing so quickly,” explains Gansam’s Chin.

There is plenty of breakout space. with some affiliates linked to neighbours via the central boulevard – the idea is that this will bring different specialisms together. At the time of Building’s visit these areas were virtually deserted – although it was mid-morning when people were most likely to be working.

The centre comes alive in the so-called integrated support centre (ISC). Located at the heart of the campus, this is where most of the social interaction takes place. It is less clinical than the research buildings, with natural stone floors, timber detailing and brighter colours. People come to eat in the dining rooms, which seat 4,500 people and can serve 10,000 meals a day. The ISC also includes shops, healthcare facilities, creches, fitness centres and auditoriums for presenting research findings. “It’s got everything to attract the best scientists in the world,” Chin says.

Opposite is another joint facility, the shared laboratory centre (SLC). This contains all the specialised kit for research including materials simulation and 3D chemical imaging. Sharing saves money on expensive equipment and helps foster collaboration. It is also open to other research institutions. The ISC and SLC feature copper coloured cladding to demarcate these facilities from the other buildings. The centre of the campus is also a stable place for experiments as it is located far from the car parking at either end of the campus. “Some experiments take a year and are very sensitive,” says Yoon. “The vibration caused by the forces from a car braking could ruin a year’s work.”

The whole campus is built over one massive basement. This links the buildings together, with a service road running around the perimeter for deliveries to the individual buildings using electric vehicles. The basement also contains plant, with services being distributed to individual buildings via risers on each side.

The buildings extend into the basement: the ISC has private dining rooms at this level with attractive sunken gardens cut into the boulevard to bring in natural light and the SLC houses the heavy, vibration sensitive research equipment.

LG spent longer planning the science park than it took to build. The company spent six years deciding what it wanted, which parts of its business should move to the park and what working systems should be adopted, as well as finding a suitable site – former paddy fields on the west side of the city. Once it had worked up a brief, it went out to competition.

HOK won the contract in 2013, in partnership with local architect Gansam. The competition stage had involved an intense period defining the concept and site layout, which HOK senior vice-president Chris Yoon describes as a “huge investment” – it had a team of up to 14 people working on this and Gansam had 10. “We worked like dogs,” says Kyo-Nam Chin, divisional executive director of Gansam.

After securing the job, the team “had to hit the ground running” according to Yoon. As a Korean national, Yoon is familiar with the country’s famously strong work ethic and understood the need to get the job done quickly. The teams spent a year getting the designs ready for planning, and a further year on the construction documentation. The science park was built using a traditional contract with virtually no contractor involvement in the design.

Construction started in 2014. Gansam had 10 people permanently on site as it also acted as construction manager. “We worked continuously, including weekends,” says Chin. All the design decisions as the job progressed were made in collaboration with HOK, a process complicated by the eight-hour time difference. There were some mammoth teleconferences, too. “Sometimes the teleconferences would last six hours,” says Chin.

The first job was to construct a massive basement that covers the entire site, which involved excavating 240,000m3 of earth. The ground works were speeded along by 24-hour working, then the rate slowed down to 10-hour days once the superstructure stage was reached. The labs feature concrete frames to help dampen vibration, with some offices built from steel. Prefabricated facades helped with meeting the demanding timescale. At the project’s peak, 7,200 workers were on site.

The first phase of 20 buildings completed in 2017, with the remaining six to be completed by 2022. LG says that researchers are “very satisfied” with the science park, but it will be some time before it can tell whether this new way of doing science has paid off.

LG’s innovation centre

Deep inside the science campus is an area dedicated to showing off LG’s latest technology. This includes the latest flat TVs, just 4mm thick, and roll-up TV screens – a 65in screen rises automatically out of a 150mm-high box to reveal a display of startling quality. Other domestic appliances include fridges that open automatically with a wave of the foot and send temperature settings to a connected cooker when programmed with a recipe. One of the most compelling gadgets is a dry-cleaning wardrobe – suits are steam-cleaned then gently heated and shaken to remove creases, and a common feature in Korean homes. There is also a big automotive focus – car batteries with a range of over 280 miles, heads-up displays and small screens just inside the passenger and driver’s doors to replace mirrors, a feature useful for anyone who lives on a narrow street. And, inevitably, there are robots: ones to mow the lawn, others for automated airport terminal cleaning and more frivolous ones that serve drinks.

No comments yet