Urban regeneration planning can tackle both sustainability and levelling up agendas if each area is considered according to its individual needs, Stefanie O’Gorman and Rebecca Dillon-Robinson of Ramboll write

The transformation of our town centres in undervalued areas across the country to be fit for the future is an ambition that many were hoping the government’s much-delayed levelling up white paper would address. However, the piecemeal nature of the funding set out in the paper falls short of delivering the transformational change needed to create future-proofed liveable places.

Although it addresses many of the factors needed to drive levelling up – such as housing, public realm and mobility – without considering all of these aspects holistically and embedding climate resilience and the transition to net zero in the process, the funding will not deliver the value that is needed in the long term.

20-minute neighbourhoods: an effective place-based solution

So, what does a holistic levelling up strategy look like in practice? We recently worked with ClimateXChange to develop an evidenced-based ambition for the Scottish government to implement 20-minute neighbourhoods across urban and rural contexts as a nationwide strategy. The work offered a vision of how levelling up can be put into action.

Twenty-minute neighbourhoods – places designed so that residents can access services within a 20-minute walk from their home – can form integral parts of climate action strategies that reduce dependence on motor vehicles and facilitate active travel.

Important lessons can be learnt from the research about how to empower local authorities to take a truly place-based approach, tailoring the strategy to investment which suits their needs. This contrasts with the white paper’s approach of placing the burden directly on local authorities in a bun-fight for funding. After all, different communities have different needs.

As part of a whole Scotland baselining exercise, we looked at data across prosperous areas (such as Pitlochry and Tollcross in Edinburgh) as well as some of the most deprived areas (such as Haghill in Glasgow). This provided a simplified framework of how the 20-minute neighbourhood concept can be applied, with a view to enabling more detailed assessments of individual neighbourhoods in future.

The UK government’s levelling up approach of separate funding pots would simply not deliver an effective place-based and people-centered outcome for towns such as Haghill with their complex needs

Most notably, the review of Haghill demonstrated how complex it can be to fit a national-level assessment into local conditions. For example, many of the shops and green spaces in Haghill are located in or around an out-of-town shopping centre the other side of a large main road and railway line from the residential neighbourhood, but within an 800m distance. This makes these services difficult to access on foot and largely only accessible by car.

It could be that there is a simple solution to providing a walkable route to these services, and given that they are within an accessible distance, which could transform the experience of those living in Haghill and their ease of accessing day-to-day services and green spaces without the need of a private car.

Alongside providing a link to these services, it would be important that the quality of the whole walking network was considered to encourage people to use it. The community should be involved in defining where interventions would make the most difference, for example a priority might be to tackle crime hotspots.

Making a deprived neighbourhood such as Haghill more walkable would also support efforts to tackle public health deprivation and inequality, which is a key factor of inequality in Scotland.

The UK government’s levelling up approach of separate funding pots would simply not deliver an effective place-based and people-centered outcome for towns such as Haghill with their complex needs.

Lessons from global examples

Where place-based approaches have been successful internationally, community participation which goes beyond just engagement and consultation has been rooted in the delivery process. In Paris for example, 10% of the city’s spending is allocated according to participatory budgeting processes.

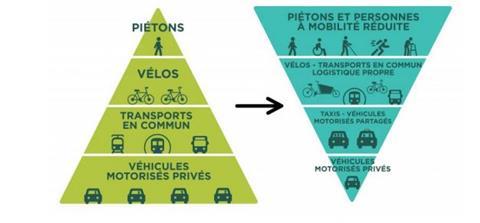

Hyperproximity plans for Paris

Meanwhile in Melbourne, communities were involved directly in implementing interventions for three pilot 20-minute neighbourhood projects. Communities helped to identify places where enabling active travel between schools and shops would have an impact. These in turn acted as a trigger to enabling wider mobility improvements in the communities.

New York has allocated $120m to 706 community-designed projects since 2012, such as local park revitalisations or IT infrastructure upgrades for community venues. Engagement was so positive that the data organisation responsible built an online community in response to participants wanting to know what happened to the projects they had voted for.

Real success on the ground requires bespoke measures designed for a particular place in response to the community’s needs. There is no one-size-fits-all option.

Unless public participation is a pre-requisite to funding, communities risk being left out in the decision-making process. This ultimately means the solutions are not “owned” by the local people and are less likely to enable behavioural change.

The elephant in the room

Most glaringly absent from the levelling up white paper is the need to prioritise climate resilience and adaptation. We urgently need to embed positive climate outcomes (net-zero and resilience) into funding decisions, otherwise we are simply not investing wisely for the future.

The role of 20-minute neighbourhoods in the green recovery was identified by the Scottish government as part of its climate resilience plans and, specifically, its aim to support efforts to realise a 20% reduction in car kilometres by 2030. This presents a compelling example of how urban regeneration planning can tackle both sustainability and levelling up agendas.

If the levelling up agenda is to succeed it must deliver long-term value through government investment focused on tangible outcomes of liveability and prosperity for communities right across the UK. Most crucially, it must have climate resilience at its heart to prepare for the future.

Milan case study

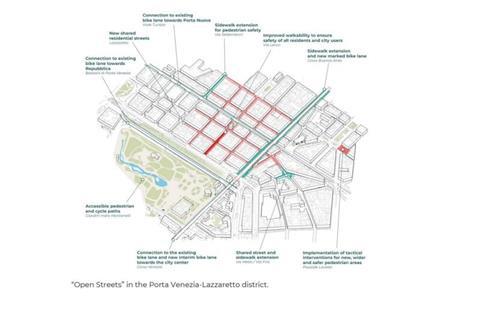

Milan announced it would host a pilot scheme for “rethinking the rhythms” of the Lombard capital. It has taken a 15-minute city framework approach to support its recovery, aiming to guarantee that essential services – particularly healthcare facilities – are within walking distance for all residents, while preventing a surge in car travel after the end of lockdown. Plans included:

- Creating new 35km of new cycle paths, some using signage only

- Increase the coverage of low speed zones (30m/hr) and residential streets which will have predominantly pedestrian and cycle movements

- Widen pedestrian paths through the widening of sidewalks

- Provide for temporary pedestrianisations in neighbourhoods by expanding the offer for children’s play and physical activity

- Implement new urban planning interventions within specific locations

- Facilitate the provision of external tables and chairs are bars and restaurants

Stefanie O’Gorman is director of sustainable economics and Rebecca Dillon-Robinson is a senior urban planner at Ramboll

No comments yet