A scheme to preserve and display the Mary Rose along with its artefacts for the first time marks the start of a special on design for conservation. Also featured are projects for the Bovington Museum, the British Library and the Sistine Chapel – but first, Stephen Kennett brings you the shipping news...

- Designing for conservation is a specialist art. Here, three high profile projects unveil how to protect ancient relics and buildings from light, air and all other contaminants.

- Air conditioning stabilises the environment at the Sistine Chapel.

- A risk-analysis based approach to book conservation in the British Museum.

- Cost effective conservation of tanks – the military kind – at Bovington in Dorset.

- The specially designed hot-box, a temperature stabilised space for the Mary Rose.

On my arrival at dry dock number three in Portsmouth Historic Dockyard, I’m handed an all-in-one protective suit and a hard hat with its own built-in filtered air supply. Perhaps I look worried, because Timothy Lloyd of Gifford Consulting hastens to reassure me it’s just a precaution: “conditions inside the ‘hot-box’ are perfect for breeding legionella,” he says, by way of explanation.

Dry dock number three is the final resting place of the Mary Rose, the Tudor warship that was raised from the bed of the Solent in 1982. The 24 years since then have been taken up with the painstaking task of preserving the 500 year-old remains, which currently involves spraying the timbers with preservative 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

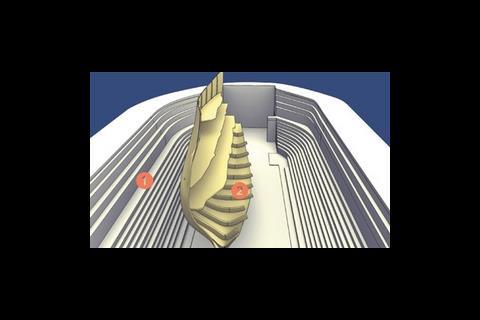

Climbing down the granite steps into the bowels of the dock, you begin to appreciate the challenge they faced. At the centre of the dock is the hull, cocooned in an enclosure of foil-lined insulated blankets - the ‘hot-box’ referred to by Lloyd. Temperatures inside here are kept at a constant 25-27ºC while a fine mist of polyethylene glycol (PEG) preservative solution is sprayed over the timbers. This process is critical and can’t be interrupted.

However, the PEG solution is corrosive and attacks the metal pipework, ductwork and plant that is crammed into the spaces around the dock. Recent improvements to the sealing of the ‘hot-box’ and storage tanks have helped improve this, but it is still a difficult environment in which to work and maintain services.

The spraying process is due to continue up until 2011 or 2012, when the drying phase of the hull begins. If all goes to plan this will be completed by 2016, when the timbers should be stable. But before then, a new museum must be constructed around the existing facilities.

The final voyage

Unfortunately, waiting until 2016 to re-house the only surviving Tudor warship in the world isn’t an option. Its current home, the Wemyss building – a lightweight steel frame with a double stressed-skin construction – was erected over the dry dock in the ‘80s and is now nearing the end of its limited lifespan.

So at the end of 2004, in the first stage of what the Mary Rose Trust calls ‘The Final Voyage’, it launched a competition to design a museum for the ship and the thousands of artefacts recovered from the sea bed.

The continuing conservation process and the need to keep the facilities open to the public throughout construction meant there were huge technical and logistical design challenges.

The most critical of these is the ongoing spraying of the PEG solution, which can’t be turned off for any longer than an hour at a time. This whole process is carried out within the hot-box. As if that isn’t enough, there are further constraints. The dry dock dates from 1803 and is a scheduled ancient monument in its own right, which limits intervention.

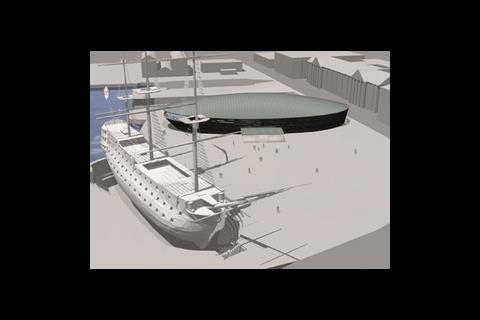

The winning proposal came from a team including Wilkinson Eyre Architects, along with interior architects Pringle Brandon and environmental and structural engineers Gifford. It is an elliptical, low, wooden-clad building that sits over the dry dock enclosing the ship as well as the existing ‘ship hall’.

The shape of the plan was dictated by the roof, which takes the form of a parabolic shell. Structurally, this is very efficient, provides long spans and, most importantly, it can be cast in lightweight concrete on-site and craned into position in a single piece, which will speed up construction and minimise the risk of damage to the ship without the need to construct a substantial crash deck.

According to Allan Hutton, M&E engineer with Giffords, the roof is something of a compromise. “Whereas the structural engineers wanted it to be as lightweight as possible, we wanted to make it as heavy as possible because from an environmental point of view we want it to have thermal mass.”

With the majority of the building sunk into the ground, the optimised roof and small windows, the hull is in a reasonably stable environment which should make it easier to maintain environmental conditions inside the main hall.

Start date

Construction of the museum is scheduled to begin in 2008. As the shell of the new building starts to go up around the existing ship hall, work will start inside to revise the galleries so that public access can be maintained while relocating existing plant and installing new utilities.

The hot-box is currently suspended from the Wemyss enclosure and only when the new shell roof is completed and the hot-box re-supported can dismantling of the Wemyss building begin. Installation and commissioning of the services and the fit-out of the galleries should be completed by the end of 2009, at which point the museum will open to the public. With the exception of the installation of dedicated air-handling plant and ductwork ready for the drying phase of the hull construction, work will then enter a stand-down period.

Spraying of the hull will continue up until 2010-2012, depending on its condition, but as soon as the conservationists say the word, it will switch into the drying phase, which will take place in the hotbox. “We always thought they would want to dry it relatively slowly so that the hull didn’t crack or move, but they want to dry it as quickly as they can,” reveals Hutton. The challenge is to make sure the timbers don’t dry locally. “If one bit dries quicker than another, it will crack and come apart,” says Hutton. “The conservationists think most of the moisture will come out in the first year, but it will take about five years before it is fully stable”.

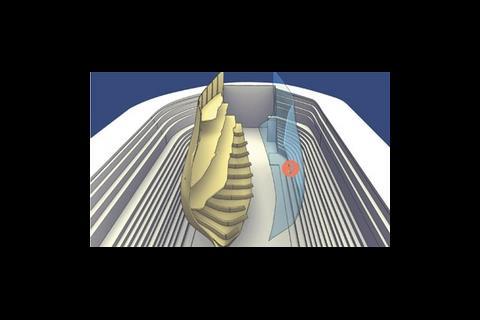

For the quick-drying phase, Gifford is proposing to use fabric ducts to deliver air across the timbers at no more than 0.15 m/s to prevent localised drying. These will be hooked onto a stainless steel and titanium suspension system which will be installed over a three-week period while the spraying of the hull is still taking place. “As soon as the sprays go off, we’ll be in there with the fabric ducts and they’ll plug straight into the ventilation plant already installed,” says Hutton. Stale air will be drawn out at the top of the hot-box and re-circulated.

For the first six months of this drying stage the spray equipment will be left in-situ, ready to start up again in case the hull should start to crack or move. In such an event, the fabric ducts can be quickly removed and the sprays turned back on, buying the conservationists time to rethink their strategy.

By 2016, the drying process should be finished – at which point the hotbox will be dismantled and for the first time the Mary Rose, the virtual hull and the exhibit galleries will sit in the same space.

The environmental conditions for each of these areas has yet to be established, but the ship hall is likely to be maintained at 18C +/- 3ºC and 45-55% RH, while the galleries will be held at 21ºC +/-3ºC and 40-60% RH. Exhibits that require tighter environmental control will be housed in separately contained and environmentally treated display cabinets.

One of the most critical aspects of this project is the air movement around the hull. Consistent velocities across the timbers are required to promote uniform temperature and humidity and maintain stability.

Gifford carried out CFD analysis to determine the ideal strategy for delivering the air and found the best solution is to introduce the supply at a number of levels within the ship hall using directional jets. This will help prevent stagnation and create an environmental cocoon around the ship, explains Hutton. “The conservationists aren’t entirely sure of the conditions they need, so we’ve got to build a bit of flexibility into it.”

Managing carbon emissions

The job of conserving the Mary Rose is an energy intensive process, dominated by the electrical loads of the chillers and fans needed to maintain the close control environmental conditions. The design team has set a carbon emissions target of 120 kgCO2/m2/y. Part of the strategy to achieve this is to use individual air-handling plants for areas of the museum with differing environmental requirements and patterns of use.

The ship hall and display cabinets will run 24 hours a day throughout the year, while automatic controls and time switches will be used in the other areas. Maximum use of recirculation will also be made to recover waste heat.

There are also proposals to incorporate renewables into the scheme to generate at least 10% of the energy requirements. These include solar thermal hot water, biomass boilers, desiccant cooling and rainwater collection. Sea water might seem an obvious solution for cooling, but the dry dock’s status as a scheduled ancient monument makes it difficult to install the infrastructure to access it.

At this stage, the design has been worked up to RIBA Stage C and costed to Stage L. The next phase is to raise the money to build it. The capital cost for the project is around £23m, the M&E services representing around 35-40% of this. The Mary Rose Trust is hoping that the Heritage Lottery Fund will grant up to £13m, with the Trust raising the remainder. The aim is to complete the museum in time to mark the 500th anniversary of the ship’s launch.

Client: Mary Rose Trust

Architect: Wilkinson Eyre Architects

Interior architect: Pringle Brandon

Consulting engineers: Gifford

Cost consultants: Davis Langdon

Downloads

Source

Building Sustainable Design

Postscript

Original print headline: "Slowing the march of time" (Building Services Journal, July 2006)

No comments yet