The government is calling for a new generation of garden towns and villages to ease the housing crisis. More sophisticated masterplanning approaches are needed to deliver these complicated projects within required timeframes and meet realistic budgets, explain Aecom’s Patrick Clarke and Paul Wilcock

01 / Background

The 2017 Autumn Budget statement committed the government to building 300,000 homes a year across England by 2021 including the construction of five new garden towns in the “brain belt” linking Oxford, Milton Keynes and Cambridge. This announcement builds on an established and increasingly successful policy initiative in which the government is already supporting the building of 24 garden towns and villages, which collectively have the potential to deliver 220,000 homes.

This return to the construction of large-scale new communities on greenfield sites is a significant challenge given the complexity of planning and building new communities from scratch in a highly regulated environment with many competing agendas and interests.

Cost and viability issues are key considerations from the outset as new garden towns and villages require the full range of physical and community infrastructure to be provided on a phased basis to meet the needs of the new community as it grows. While much of this infrastructure can be funded from the uplift in land values from agricultural use to residential-led development, the very high cost of strategic infrastructure inevitably places pressure on viability and cash flow.

Recognising these challenges, the government has launched a £2.3bn housing infrastructure fund (HIF) to support housing delivery, with capital grants to eligible projects on a competitive basis.

The range of expertise needed to take a new community project from concept to completion encompasses the full spectrum of planning, design, cost, environment, engineering, construction and project management skills. Delivery success will require highly integrated and effective working across disciplines, and key to this is creating the right masterplan framework to guide the development of the new communities.

What is a garden town or village?

The garden towns and villages initiative builds on the success of the original garden cities, which were built at Letchworth and Welwyn Garden City in Hertfordshire in the early 20th century.

These new communities were well planned, including employment and other facilities as well as generous green space, and funded the provision of infrastructure from the rises in land value that came about from the development of agricultural land.

The Department for Housing, Communities and Local Government’s prospectus for locally-led garden towns and villages defines a garden town as a community of more than 10,000 homes and a garden village as a settlement of between 1,500and 10,000 homes, which is freestanding from existing communities.

The Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA) has published guidance on principles and model approaches to the development of garden cities that is also relevant to the planning of garden towns and villages.

For more information, go to: www.tcpa.org.uk/pages/category/garden-cities.

02 / Current issues in the delivery of garden towns and villages

Large-scale new community projects typically undergo a very long, complicated and uncertain planning and development process. A period of between five and 10 years has been pretty much the norm in terms of the time taken between the beginning of the planning process and the start of construction on site.

Part of the reason is a complex statutory planning process that lacks a strategic framework for planning large-scale projects across local authority boundaries. Another obstacle is the level of objection and controversy raised. But even where projects have planning permission or are allocated in a local plan, they can be dogged by delays and uncertainty. Implicit in all of this is that delays cost money.

For example, the need for new or improved major highways may be unclear because of the lack of an up-to-date transport model or agreement over whether the need for the works is being triggered by the development or by background traffic growth. Similar issues arise in relation to requirements for new or reinforced utility infrastructure or the diversion of existing above- and below-ground utilities. The costs and lead times relating to strategic infrastructure items such as these can be the difference between a viable project and one that requires grant support.

The assessment and mitigation of potential environmental impacts is another area of significant complexity. This may include consideration of the effects on sites designated under European or UK legislation, the management of flood risk, landscape and visual impact, noise and air quality issues, the protection and enhancement of heritage assets (archaeology tends, by its very nature, to be a significant unknown).

Similar issues can arise in terms of requirements for social and community infrastructure, with the costs of secondary school provision being a source of particular uncertainty, given the changes to the arrangements for the delivery of schools and how difficult it is to forecast school place requirements into the medium/longer term.

Impacts on cost and viability models

Issues such as these are complex enough in isolation, but greater complexity often arises as a result of the interdependences between issues. For example, changes to the design of a significant junction could impact on the outputs of a traffic model, which would have knock-on implications for the assessment of noise and air quality. And that, in turn, might have implications for the utilisation of land for sensitive uses such as homes or recreation, which can have implications for the development capacity of the site and the overall cost and viability model.

As a general principle, the range and complexity of the issues to be addressed increases with the scale of the project. The consequence of this is that the number of developers with an appetite for delivering new communities of more than around 3,000 homes is fairly limited.

The design and investment approach is also shaped by the uncertainty they need to overcome, with promoters understandably holding back investment in design development until the deliverability of the project is more certain. In practice, this can mean doing no more than is needed to move to the next stage of the planning process, or focusing on overcoming one key issue at a time rather than committing to a more comprehensive approach.

This iterative approach fails when other issues arise that had not been on the radar as important areas for consideration. Projects can be particularly vulnerable to this risk when design development runs ahead of the evidence base that is needed to support it through the planning and development process.

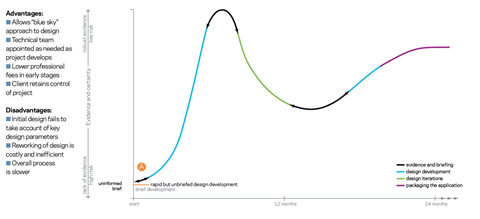

This is illustrated conceptually in Figure 1, which shows how a scheme can appear to be a fully resolved design, only to fall apart when it is assessed against the full range of technical requirements and/or is subject to the scrutiny of statutory consultees. As the diagram shows, schemes then need to work through a costly redesign process to address technical issues that had not been properly considered first time around and this delays the completion of the masterplan.

This fuller consideration of all of the issues can then have significant issues for the project cost plan and the viability of the scheme. Where community and stakeholder engagement has already taken place, it can be damaging to the credibility of the project if new issues need to be raised or commitments to the provision of community benefits scaled back because of unforeseen costs.

03 / A more integrated design approach

A more rigorous and cost-sensitive approach is needed to deliver a new generation of garden towns and villages within the timescales and resources available. One approach that could contribute to meeting this need is Aecom’s “Masterplanning ie” methodology. This is an integrated and evidence-led approach to master-planning that has been developed to support the delivery of large-scale and complex projects and to overcome many of the problems associated with conventional approaches.

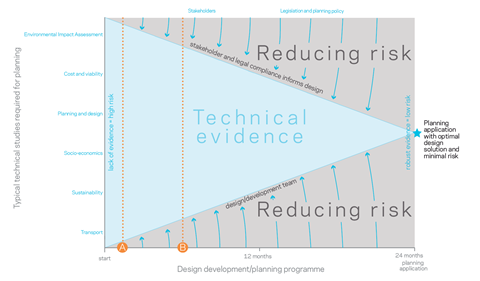

Figure 2 shows in conceptual terms how the design of a complex project begins with little evidence and therefore the maximum level of uncertainty and risk. It then develops through a process of site analysis, engagement with regulatory agencies, other stakeholders and community groups and this enables the design to be evolved into a final masterplan. At this point all the key risks and uncertainties should have been eliminated and the project should be ready to be consented and taken into the delivery stage.

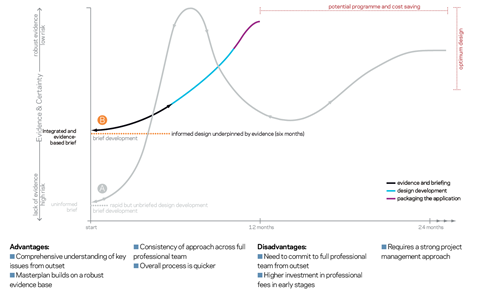

Rather than testing a draft design solution against an evidence base, “Masterplanning ie” brings the technical evidence to the beginning of the process so that the development of masterplan options is fully informed by a comprehensive evidence base from the outset. This technical evidence would be required in any event but bringing it forward to the beginning of the process enables masterplan options to be developed and tested in a single process without unnecessary iteration and abortive work.

The difference between this and the conventional masterplan approach is shown conceptually in Figure 3. It can be seen that although the “Masterplanning ie” approach begins with a longer process of briefing and evidence gathering, it then builds smoothly to a completed masterplan in a shorter overall elapsed time.

This approach brings together around 20 different professional skill sets that would typically be required to support the development of a masterplan for a new community. Collectively these skill sets address the environmental, economic, social and physical dimensions of sustainable development.

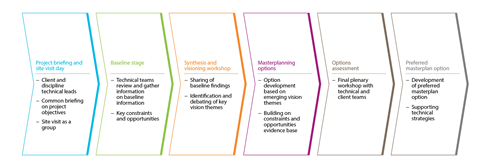

Integrated working across the team and with the client group is enabled through a programme of plenary site visits and workshops. The process is tailored to each project but typically includes the main stages shown in Figure 4. This provides an overarching masterplan process, which can then be set within a wider project plan encompassing stakeholder and community engagement, client review and sign-off processes.

04 / Using the approach in practice

The approach was first applied in support of the Manydown Project at Basingstoke (see case study overleaf in Section 5) and has since been used on a further five new community masterplan projects. These have ranged in scale from around 1,000 to 10,000 homes in greenfield and brownfield contexts, for public and private sector clients. In most cases, Aecom has provided the full range of technical input but in one example specialist inputs have been provided by a range of separate consultancies appointed directly by the client.

In each case, the approach has succeeded in enabling a smooth masterplan development process without unnecessary iteration or abortive work. However, the benefits observed have been much wider than just providing an efficient and cost-effective process. Most importantly, the approach is enabling better masterplan outcomes to be achieved through the early identification of key issues and opportunities and a more holistic approach.

From a cost management and deliverability perspective, the approach enables cost considerations, including the relationship between phasing and cash flow, to be factored into the development of the masterplan from the outset. This early input is crucial in ensuring that masterplan options are viable and deliverable as they are developed, rather than cost simply being used to discount options after they have been developed without adequate regard for cost considerations.

At the same time, early engagement with the full range of technical specialists allows a more informed understanding of detailed elements of the design proposals, which should support more accurate estimates of cost at the early stages of a project. This enables investment decisions to be made with greater confidence.

Professional skills that are needed to support a garden community masterplan

- Archaeology

- Built heritage

- Cost consultancy

- Drainage

- Ecology

- Economic development

- Flood risk assessment

- Geotechnical engineering

- Infrastructure

- Landscape and visual assessment

- Masterplanning

- Minerals

- Noise

- Property market

- Social infrastructure

- Sustainability

- Transport planning

- Utilities

- Waste and recycling

- Water resources

- Town planning

05 / Looking to the future

The “Masterplanning ie” approach simply restructures the masterplanning process so that it is informed by a technical evidence base from the outset. This technical evidence would be needed in any

event but front-loading it can accelerate the creation of viable and delivery focused masterplans.

Delivering 300,000 homes a year including a new generation of garden towns and villages is a defining challenge for the construction and built environment professions. A more integrated design approach to the masterplanning process is one way in which we can rise to the challenge.

Case study: Manydown, Basingstoke, Hampshire

Manydown is a strategic 800ha (circa 2,000 acres) site to the west of Basingstoke. In 1996, Basingstoke and Deane borough council (BDBC) and Hampshire county council (HCC) jointly acquired a long leasehold interest in the whole site in anticipation of the longer term growth of Basingstoke.

Using the “Masterplanning ie” approach, Aecom undertook a comprehensive baseline analysis of the entire site to identify the principal constraints and opportunities impacting upon development in the short, medium and longer terms. This analysis confirmed the northern part of the site as the most suitable for the creation of a sustainable new community within the local plan period to 2029.

A number of alternative masterplan options were then developed and a preferred approach identified. The preferred approach and supporting evidence base was submitted to the Local Plan process and, following an Examination in Public, the site was allocated for the development of 3,400 homes, supported by all of the necessary infrastructure and community facilities.

This first phase of development at Manydown is part of a broader opportunity that could deliver 10,000 or more homes in a way that is comprehensively planned and underpinned by the necessary investment in strategic infrastructure. The strategic importance of the project has been recognised by government, which is supporting Basingstoke as one of nine garden towns across England.

06 / About the cost model

This cost model is based on a notional new garden village of 5,000 residential units on a 350ha greenfield site in the south-east of England. The site is assumed to be generally on level or gently sloping land with no significant level changes. Access to the site is assumed to be good.

The details cover the work required by the master developer/site promoter to prepare the site and provide primary infrastructure and community facilities to enable parcels/plots to be disposed to others for residential led development. It is recognised that there is likely to be some supporting employment and retail, although the predominant land use will be residential.

There are a number of different options for how the works can be procured by the master developer/site promoter, recognising as well that overall delivery of a project of this nature could typically range from 20 to 30 years. In this respect, it is assumed that the project would have a duration on site of 25 years, equating to the average delivery of 200 residential units a year.

As such, this cost model assumes that a main contractor would be appointed to deliver the initial phase of works, with the contract being subject to review for future phases.

The costs are all at January 2018 prices and exclude inflation and VAT.

07 / Cost model

| Total (£) | £/resi unit | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ON-SITE WORKS | |||

| Demolition, site clearance and enabling works | 4,000,000 | 800 | 1.49 |

| General demolition and site clearance – albeit, given the nature of the site these will be limited with decontamination and archaeological investigations assuming these are low risk | |||

| Strategic earthworks | 5,000,000 | 1,000 | 1.87 |

| Cut and fill across the site assuming a balance within each phase, thereby avoiding the need for disposal/importation of material | |||

| Highways | 10,000,000 | 2,000 | 3.73 |

| Primary road and secondary road network, assuming the provision of parcel plots for disposal of around 50-100 units | |||

| Drainage | 7,500,000 | 1,500 | 2.8 |

| Foul and surface water network with connections for foul to the existing sewerage treatment works off-site and for surface to existing watercourses off-site. Limited diversions of existing drainage | |||

| Utilities | 7,500,000 | 1,500 | 2.8 |

| Electrical, gas, potable water and communications network. This assumes delivery by a multi-utility service company (Musco) with benefits of reduced capital cost. Provision of common services trench for utilities by main contractor and other builders’ work. Limited diversions of existing utilities | |||

| Landscaping | 20,000,000 | 4,000 | 7.47 |

| Formal and informal open space, woodland and allotments | |||

| Noise attenuation | 2,000,000 | 400 | 0.75 |

| Provision of bunding/screening to mitigate the impact of major highways in the locality | |||

| Waste management | 1,000,000 | 200 | 0.37 |

| Provision of recycling areas on site, but assuming no requirement for a new civic amenity facility | |||

| OFF-SITE WORKS | |||

| Highways | 25,000,000 | 5,000 | 9.33 |

| Assumes that there will be a new main access point to the site from an adjacent A road requiring a new grade separated junction. Allowance for other highways works comprising a combination of new junctions and widened/enhanced existing junctions. Note: assumed that there are no new railway works required | |||

| Drainage | 5,000,000 | 1,000 | 1.87 |

| New foul water connection; approximately 5km to the existing sewerage treatment works, but assuming sufficient capacity exists at the works. New outfalls to existing water courses for surface water drainage | |||

| Utilities | 20,000,000 | 4,000 | 7.47 |

| New primary electrical substation and connection to the site, new intermediate gas main, new potable water supply from existing reservoir and new connection to existing communications network | |||

| Landscaping and pedestrian/cycle network | 2,000,000 | 400 | 0.75 |

| Provisions of off-site mitigation measures for landscaping and pedestrian/cycle network | |||

| SECTION 106/COMMUNITY FACILITIES | |||

| Education | 50,000,000 | 10,000 | 18.67 |

| Early years, primary schools, secondary school and contribution to post-16 education | |||

| Healthcare | 6,000,000 | 1,200 | 2.24 |

| Primary care facility and contributions for mental health care and extra care facilities | |||

| Community and civic | 4,000,000 | 800 | 1.49 |

| Multi-use community centre and contributions for police, fire and ambulance stations | |||

| Indoor sports | 4,000,000 | 800 | 1.49 |

| Provisions and/or contribution for sports hall, swimming pool and other related facilities | |||

| Travel allowances | 3,000,000 | 600 | 1.12 |

| Bus subsidies and travel planning measures | |||

| MAIN CONTRACTOR COSTS | |||

| Phasing and temporary works | 4,350,000 | 870 | 1.62 |

| Provision of temporary hoardings, highways, drainage and utilities connections and landscaping in relation to the nature of the works and phasing requirements. This is based on 2.5% on all works | |||

| Preliminaries | 22,294,000 | 4,459 | 8.32 |

| Management, accommodation, health and welfare facilities, insurances, bonds etc at 12% on all works | |||

| Overheads and profit | 10,032,000 | 2,006 | 3.75 |

| Overheads and profit at 5% on all works | |||

| ADOPTION FEES, ESTATE MANAGEMENT AND PROFESSIONAL FEES | |||

| Adoption fees for on-site highway works | 2,000,000 | 400 | 0.75 |

| This covers all works from plot edge to plot edge that are adopted | |||

| Adoption fees for off-site highway works | 6,000,000 | 1,200 | 2.24 |

| This covers all works | |||

| Estate management | 5,000,000 | 1,000 | 1.87 |

| Assumes that the landscaping will not be adopted but will be the responsibility of the master developer/site promoter to maintain and manage | |||

| Professional fees and survey costs | 18,000,000 | 3,600 | 6.72 |

| Design and project management team covering the planning application stage and the design procurement and delivery stages of the project | |||

| DESIGN DEVELOPMENT AND CONSTRUCTION CONTINGENCY | |||

| Design development and construction contingency | 24,167,000 | 4,833 | 9.02 |

| Based on 5% for design and 5% for construction works | |||

| TOTAL CONSTRUCTION | |||

| TOTAL | 267,843,000 | 53,568 | 100 |

Downloads

Cost model garden towns jan 2018

Excel, Size 11.47 kb

Postscript

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Aecom colleagues and clients to the development of the “Masterplanning ie” approach, and in particular Alex Tosetti, who provided important insights to guide the early conceptual thinking.

No comments yet