Evacuating towers by using stairs in the event of a fire is a slow process but has long been the accepted strategy. At 22 Bishopsgate, Lipton Rogers has come up with a speedier approach – using a specially developed lift evacuation strategy. Thomas Lane reports on how this will work, changing safety culture and the installation cost

For anyone working in a multistorey office building the announcement: “A fire has been reported in the building. Please leave the building immediately. Do not use the lifts,” is all too familiar.

Usually a fire drill, the routine involves shuffling down the fire escape stairs, a process that gets slower and slower towards the bottom as more and more workers from the lower floors join the crush to get out.

The move towards ever-taller office buildings, particularly in the City of London, is making the problem worse – it can take what feels like an age to get everyone out.

The team behind 22 Bishopsgate have decided to tackle this challenge head on and have devised a strategy to use the lifts to get office workers out of the building in a fire, for the first time in the UK.

There are lots of good reasons to use the lifts. The 62-storey 22 Bishopsgate will be the second-tallest building in Europe when it completes in 2019, so getting people out in the event of fire will be a major challenge, especially as it will be routinely occupied by 13,000 people.

In fact the development is designed for up to 30,000 people, should occupiers choose to cram workers in – equal to the population of Sevenoaks in Kent.

It features 24 double-decker lifts, the equivalent of 48 conventional lifts, so using these to get people out would be much, much faster than the stairs. “It’s silly not to think of using the lifts for evacuating people in a fire,” says Peter Rogers, co-founder of developer Lipton Rogers.

Romain Hourqueig is the director of UK fire engineering at WSP and engineered this solution. He says the top three floors, set to be populated by 1,457 people, could be evacuated in just 20 minutes using the lifts, one-third of the time it would take to get people out using the stairs.

Are concerns about evacuating people safely in a fire in the wake of the Grenfell tragedy the reason the team have opted to use lifts for evacuation at 22 Bishopsgate? According to Hourqueig the reason is much more prosaic.

“Construction (Design and Management) Regulations,” he explains. “Have you ever tried to walk down 61 floors of stairs? If you are perfectly healthy you will still feel really dizzy and tired.”

“Some people are very fit but an awful lot aren’t,” chips in Rogers. He points to figures showing that obesity is a rapidly growing problem, saying 47% of men and 36% of women between 21 and 60 will be classified as obese in the UK by 2025.

When the Address Downtown, a 63-storey residential and hotel building in Dubai clad in the same material as Grenfell Tower went up in flames in 2015, only one person died – from a heart attack caused by the exertion of going down the stairs.

Why so unusual?

The reason that fire evacuation lifts are so rare is cost. Regulations demand that lifts run inside fire-rated shafts, the lifts need a dual power supply and the cars must be pressurised to protect against smoke ingress.

Valuable real estate has to be sacrificed to dedicated lobbies, which must not contain any combustible materials, ruling out the space for other uses. At 22 Bishopsgate, each floor would need a 100m2 fire lobby, adding up to 6,000m2 in total. “That’s three floors,” says Rogers.

The 22 Bishopsgate team have come up with a neat solution that circumvents these onerous requirements. “We are making the best use of the existing design,” explains Rogers.

The building features fire-hardened slabs with a two-hour fire rating separating a floor from the one above, at levels 26, 42 and 58. Lifts in the building serve each of the four zones created by the unbreachable slabs so it is possible to go to the top of the building without needing to change lifts in sky lobbies. Each bank of lifts has a motor room just above the fire-hardened slab that is encased in concrete.

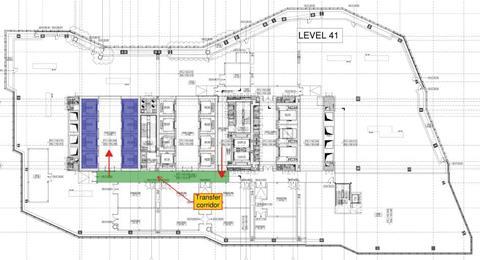

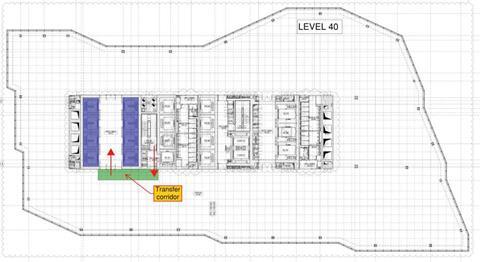

The escape strategy is elegantly simple. If a fire is detected on, say, the 54th floor, workers on that floor and the floors above and below go down the fire escape stairs to the 40th and 41st floors, which sits just below the hardened slab that separates it from the fire-affected zone above. They can use the lifts to evacuate the building, safe in the knowledge that these are protected by the slab above.

If there is a fire on the ground floor, people can evacuate via a set of fire stairs on level seven at the back of the building. If there is a fire higher up the building, say on the 20th floor, this does mean people will have to use the stairs to evacuate from all levels.

Like most seemingly simple ideas, there is much more to using the lifts for evacuation than meets the eye. The floors at the top of each fire escape zone feature a self-contained transfer corridor linking the stairs to the lift lobby.

Because the building features double-deck lifts, one escape stairway and corridor serves the upper level with the other escape stairway serving the floor and lower deck of the lift below.

In the event of a fire, wardens will guide people towards the lifts. CCTV is fitted in the stairs and lift lobbies so people in the fire control centre can see what is happening and direct people using the PA system.

The use of lifts in an emergency is not compulsory and Rogers concedes this is a culture change that takes time to get used to, a process that should become embedded with the six-monthly fire drills. “At first, 10% will use the lifts, the next time 20% – until eventually everyone is using the lifts,” he says.

After people have left the lift at the bottom of the building, it will automatically go back to the top of the zone just below the fire. The lift doors have been designed to automatically close in the same way train doors close to prevent valuable time being wasted by the doors opening every time an obstruction is detected.

“We spent hours and hours with Otis getting the software right,” explains Hourqueig.

There are fire-protected power supplies to the lifts on the north and south sides of the building, which are linked so if one fails the lifts still have a supply. There are six backup generators at level 57. These are arranged in three fire-separated banks of two units; each generator has a dedicated fuel supply.

Calculating cost

How much has all this cost? Not much, according to Paul Hargreaves, Lipton Rogers construction director for this project. He says the hardened slabs and lift software were the main cost. “It’s not a significant cost in a project of this size.” A traditional fire evacuation lift strategy would have cost “millions” of pounds.

One of the downsides of being a pioneer is having to convince everyone else that your idea is a good one. In this case the team had to convince the City of London building control department, the London Fire Brigade (LFB) and the fire engineering group of the LFB that the idea was going to work.

“I can tell you they have been very tough,” says Rogers. “The whole process took over a year because it’s never been done before.”

The good news is the approach received its official blessing in May. The team reckon that now this approach has been proven it will start to become the norm on tall buildings. The days of hearing that “Do not use the lifts” announcement could be numbered.

Fire evacuation lifts in residential towers

The Grenfell Tower disaster has focused attention on the means of escape in tall residential buildings. Commercial buildings feature at least two escape stairways as the rule is to evacuate workers if there is a fire.

Building Regulations guidance states that tall residential buildings only need a single stairway, provided these are no more than 7.5m from an apartment’s front door, as the presumption is to stay put in the event of a fire.

Effective compartmentation should stop a fire spreading to other apartments – the theory that failed so disastrously at Grenfell. This led the RIBA to call for two escape stairways to be made mandatory on residential buildings of more than 11m high.

The problem with this approach is cost. According to Arcadis, a second stairway could cost £60,000 extra per floor and would mean some residential schemes would no longer be viable. Could adopting the approach used at 22 Bishopsgate for tall residential buildings provide a solution?

“It would be better,” says WSP’s Hourqueig. “The population in a high-rise is very varied and includes the very young, the old and the disabled. It is asking a lot of, say, a grandmother looking after very young children, to walk down an 80m-high stair.”

Hourqueig says one answer could be to replace the standard passenger lift with a firefighting lift. These are special lifts that are used by the fire and rescue service to transport firefighters and equipment quickly up high-rise buildings to fight fires.

A firefighting lift features a dual power supply and controls, electrical systems that are water-protected and drainage channels to prevent flooding.

According to Hourqueig, upgrading a standard passenger lift to a firefighting lift with these features would cost an additional £10,000. Pressurising the lift shaft to keep it clear of smoke would add significantly to this cost, but he points out this would be mitigated as both firefighting lifts would run in the same shaft.

Hourqueig is dismissive of RIBA’s call for a second escape stairway in new buildings, saying: “The biggest issue is old buildings.” The answer, he says, is to tighten up on all the issues that went wrong at Grenfell by making sure the compartmentation measures, such as fire doors, are up to the job.

He says external cladding systems should be checked as part of regular risk assessments under the regulatory reform order.

Hourqueig adds that retrofitting sprinklers is an expensive and disruptive undertaking; instead, he points to mist protection systems that require far less water and are now available as systems that can be fitted to individual flats.

These systems use the existing water supply and feature an under-the-sink pump to feed the water to mist distribution heads around the flat. He says, “This does bring challenges in terms of maintenance and access for landlords but at least it is a step in the right direction.”

No comments yet