Carillion was once a colossus that bestrode the construction world. Now it’s bust. As a shell-shocked industry begins to take in the enormity of the disaster, the question on everyone’s lips is, how could this happen? Dave Rogers charts the sad collapse of a once great company

There are some firms that when they go bust, the industry shrugs and says to itself: that’s contracting for you.

But there are some failures where the ramifications are so enormous that the industry feels as if it’s been felled as well. Losing Carillion is a disaster.

Its collapse feels like a verdict on corporate Britain. One former transport secretary, Andrew Adonis, said the implosion had the feeling of Enron about it – a reference to the bankruptcy of the US energy company, once a business darling whose name has since become a byword for corporate fraud.

The industry will know Carillion for what it once was – when it was a builder, when it was called Tarmac and before it started to have a rethink about what it was and pick up a ton of support services work. For construction, the second-biggest builder going to the wall, reduced to getting out the begging bowl to cope with a mountain of debt and deficits, is the biggest shock in a generation.

They lost their focus and the professionalism of the construction business went down – proven by the contracts they were signing

Former senior executive at Carillion

This week, Wates chairman James Wates revealed it was his firm that offered to tear up the severance agreement with its former boss Andrew Davies, a move that would have seen him start as Carillion’s new chief executive on Monday. A personal chastening for Davies – but for Wates, a consistent champion of the industry he has worked in all his career, this wasn’t just a Carillion crisis, it was an industry one. “We at Wates were keen to do what was right to help safeguard the company’s future,” he says.

He knew the severity of the situation. This was a contractor that helped rebuild Britain after six years of war. It built the Preston bypass, the beginnings of the M6 motorway, in the 1950s; it built the Thames Barrier; it helped build the Channel Tunnel; and it turned a derelict power station on the banks of the River Thames into a hugely successful art gallery called Tate Modern.

3

Number of profit warnings Carillion issued in five months from July to November 2017

For the industry, this news eclipses the shock back in 2000 when John Laing said it was selling its construction arm because, in short, the Laing family had had enough of watching the once blue riband contractor – its alumni read like a who’s who in construction – bleed money.

Laing was one of the few building companies that transcended its industry. Wimpey was another, Tarmac another. In the mid-1990s, Wimpey’s construction arm was picked up by Tarmac, the construction and aggregates business headed by the charismatic Glasgow-born Neville Simms who had been at the firm since the 1970s. It was an industry titan.

Now Carillion has gone bust, people will want to know why, point to a date when it all started heading south.

How Carillion changed

These revenue figures show how much the firm’s sources of income changed between 1999, the year it was set up, to 2016 – its latest set of full-year accounts.

In 1999, its services business – which it said comprised support services, property management, facilities development and building control – brought in £323m of revenue, amounting to 18% of total income, meaning that more than 80% of its £1.8bn turnover was construction work.

By 2016, construction work had shrunk to less than half its £5.2bn revenue.

| Support services | £2.7bn |

| PPP | £313m |

| Middle East construction | £668m |

| Construction (excl Middle East) | £1.5bn |

| Total | £5.2bn |

| Building | £711m |

| Capital projects | £490m |

| Services | £323m |

| Infrastructure management | £234m |

| PFI | £95m |

| Total | £1.8bn |

Source: Carillion report and accounts

Changing direction

There’s no doubt the firm changed course when Simms left and was replaced in 2000 by John McDonough, a former vice-president of FM at US firm Johnson Controls, the company that was set up after its founder invented the first electric room thermostat.

Such was the relentless switch to focus on support services at the time, it was impossible not to think that here was a firm treating cleaning toilets as though it was the answer to all contractors’ troubles. They used to be a builder, didn’t they? was the thought of many.

Within the space of two years in the mid-2000s, it bought Mowlem and Alfred McAlpine, two other firms that were also cutting ties with their historic connections as the support services craze spread among listed contractors fed up with their muddy boots image in the City.

At Carillion, construction – traditionally its stock in trade – was playing second fiddle while its supremos raved about the profits and ratings they could get out of being a support services giant. It was a business that suddenly branched out from digging holes in the ground to serving up school dinners and cleaning hospital linen.

£845m

Hit Carillion took on unprofitable contracts

One former senior executive remembers: “McDonough came in and spoke evangelically about FM, which is not a specialism; it doesn’t require specialist engineers. It requires managers and systems and unskilled staff.”

So when McDonough left in 2011 and the firm began looking again at big construction contracts under new man Richard Howson – taking on large capital jobs such as hospitals – it was left high and dry when those schemes, including its PFI hospitals in Liverpool and the West Midlands and the road bypass around Aberdeen, started going wrong. It simply did not have the right people with the right skills to identify and tackle those problems successfully.

“They lost their focus and the professionalism of the construction business went down – proven by the contracts they were signing. The skills to plan and manage these projects and the risks had pretty much left.”

The men at the top

John McDonough (left) took over from Sir Neville Simms, Carillion’s first chief executive, in 2000, a year after the demerger from Tarmac. His 11-year reign saw the firm transform from a builder into a support services giant

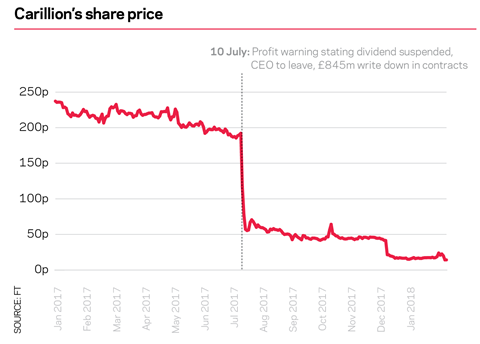

Richard Howson (centre) was appointed chief executive at the end of 2011, taking over from McDonough. He left on 10 July last year, after the firm shocked the City with an £845m writedown

Keith Cochrane (right) took over from Howson when the latter left in the wake of last July’s news about the writedown. He had been due to step down this Monday and be replaced by former Wates boss Andrew Davies

Opinion is split on Howson, who this week had moved into the spot vacated by retailer Philip Green as the most hated man in UK business, by those who remember him at Carillion.

A man whose CV included spells at Balfour Beatty and Bovis, here was a figure who to all intents and purposes knew his way around a construction site. One former staffer remembers: “I respected him enormously, as a person. He would also seek to make the right call in the right circumstances.”

Others are less kind. “The man’s a disgrace,” is the blunt assessment of the former senior executive. “Carillion had a market cap of over £2bn and now it’s worth nothing.”

8

Number of public sector contracts awarded to Carillion after its profit warning in July 2017, including a £1.3bn HS2 contract awarded in July

Government ministers have promised to look into what directors were up to and whether there is a case to answer. Cabinet Office minister David Lidington told MPs this week an investigation by the official receiver will “look not only at the conduct of the directors at the point of the company’s insolvency but also at that of any previous directors, to determine whether their actions might have caused detriment to the company’s creditors”. A day later business secretary Greg Clark said he wants this speeding up and extending to include its auditor, KPMG. “Any evidence of misconduct will be taken very seriously,” he said.

By the time it went bust on Monday, a company with a heritage stretching back over 100 years – and which only last summer had a market capitalisation of more than £1bn – had no money left. David Birne, insolvency partner at London accountant HW Fisher, said of the decision to go straight into liquidation: “It suggests there is little, if anything, of value within the company to be saved.” What a mess it had become.

The impact on its supply chain and employees is, of course, enormous. Many of its 43,000 staff will be out of a job by the end of this week, with the government saying that thousands of staff who worked for Carillion inside private sector companies were due to have their wages stopped on Wednesday.

The priority certainly wasn’t to staff, it was to the shareholders and board members. [these big companies forget what they are really all about

Wolverhampton MP Eleanor Smith

“The position of private sector employees is that they will not be getting the same protection that we’re offering to public sector employees, beyond a 48-hour period of grace,” Lidington confirmed.

Thousands of suppliers will be stuffed too. Listed firms, as they are required to, have already begun to warn shareholders of the losses they are holding thanks to Carillion’s collapse. The true scale of the disaster will take months to unravel.

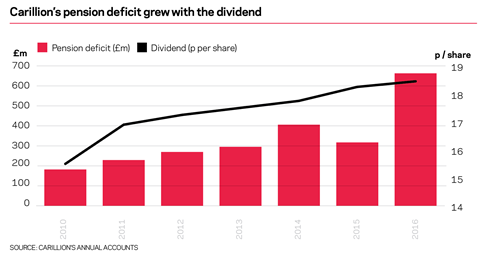

Blame rank bad management – and in September interim Carillion chief executive Keith Cochrane, who replaced the sacked Howson, appeared to do just that when he said the aim of the business going forward was to be “a lower risk, lower cost, higher quality business generating sustainable cash backed earnings” – blame botched jobs, blame the focus on support services, blame clients who don’t pay up. Whoever cops it, and it should start with the top, a company with all that heritage has gone. “It is”, James Wates says, “a sad day for the industry.”

Perhaps the final word should go to the local MP Eleanor Smith, who now has to help come up with a plan to cushion the impact of the collapse on Carillion’s 400 staff based at its headquarters in Wolverhampton. “The priority certainly wasn’t to staff, it was to the shareholders and board members,” she tells Building. “That’s sometimes the trouble with these big companies. They forget what they are really all about.”

A reminder of what Carillion once did (serving up school dinners not included)

1903

Tarmac was founded in 1903 by Edgar Purnell Hooley after he patented the road surfacing material two years earlier

1913

Listed on the Birmingham stock exchange

1958

Completes Preston bypass, the first section of what would become the M6 and opened by prime minister Harold Macmillan

1973

Completes civil engineering work on Drax power station in North Yorkshire. John Mowlem and Alfred McAlpine, both of which would later be bought by Carillion, also carried out work here

1981

Builds a road tunnel under the Suez canal in Egypt called the Ahmed Hamdi tunnel

1984

One of several contractors to complete the Thames Barrier

1994

Completes work on the Channel Tunnel

1999

Builds Canary Wharf tube station in joint venture with Bachy UK

1999

Tarmac demerges into construction business called Carillion while the aggregates division retains the Tarmac name and is bought by Anglo American the following year

2000

Carillion-owned Schal masterminds transformation of the former Bankside power station into Tate Modern

2003

Builds the iconic doughnut building at the GCHQ government communications headquarters in Cheltenham

2012

Builds the media centre for the Olympic Games in London

No comments yet