Fashion giant Monsoon is used to setting trends, so it is no surprise that the design of its new London headquarters breaks new ground. Stephen Kennett unpicks the concrete net holding up the building

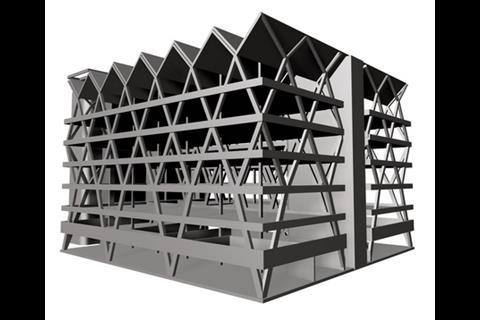

You might be used to Monsoon Accessorize stealing a march in high street fashion, but the clothing company is now taking its distinctive identity one step further with the development of its new headquarters building in London’s Notting Hill. This is not your typical speculative office development; instead the six-storey building will be held up by a giant concrete lattice without a vertical column in sight – quite a challenge for the structural engineers and contractors building it.

This is not the first time the retailer has occupied an unusual building. In 2001 it moved into its current headquarters, a former British Rail maintenance depot near Paddington Basin, renowned for its imposing concrete structure. It is the qualities of this space that the client wants to take to its new home. According to Simon Allford of architect Allford Hall Monaghan Morris, Monsoon wanted a building that had character but also kept the light industrial warehouse feel and open spaces of its current residence.

To this end it has wrapped the building in a diagrid, doing away with upright perimeter columns and installing columns that taper in size as they rise to reflect the decreasing loads placed on them. Diagrids have not been used in this guise before, according to engineer Adams Kara Taylor.

Allford Hall Monaghan Morris was keen that the lattice wasn’t just an architectural add-on but worked structurally as well, which is why they teamed up early on with AKT to develop the design.

AKT used Gehry Technologies’ Digital Project for the early design stages. This is a parametrically driven software programme. “It meant that we could build up a series of floor plates and connect them to a diagrid so that if you wanted to, say, change the floor to ceiling heights, everything changed with it, rather than pulling the structure apart,” says AKT project director Paul Scott.

This allowed the architect and engineer to quickly explore different building layouts and design options. “It also gave us a sense of how the external grid was going to look – both from the outside and inside,” adds Scott. “But most of all it enables us to quite quickly get to grips with 3D geometry, and to get back to the architect with structural feedback about whether it’s going to stand up.”

The big advantage of wrapping the building in this concrete net is the rigidity it offers. The vertical columns used in most buildings provide no lateral stiffness, which comes instead from the building’s core. “Taking the vertical columns and inclining them at an angle gave us the stiffness we would normally require from the cores,” says Scott.

This in turn gave the architect the freedom to open up the atrium and remove large chunks of solid structure, recreating the transparency of the client’s existing office. The result is large, open, unobstructed floor plates either side of a linear atrium through which rises an open staircase. Lifts, lavatories and escape stairs – the things you would find in a conventional core – have been repositioned to the south end of the building in an aluminium-clad “service tower”.

Computer-aided design tools make the manipulation of surfaces and forms very easy, and in the wrong hands that can be a dangerous thing

Paul Scott, AKT

With the design settled, the next issue was how to build it. “Computer-aided design tools make the manipulation of surfaces and forms very easy, and in the wrong hands that can be a dangerous thing,” says Scott. “If you’re going to start working in this manner you need make sure it is buildable.”

Discussions began with Expanded, Laing O’Rourke’s concrete frame arm, to come up with a way of constructing the building. Precast concrete would have suited the design, but cost was an issue and the varying size and number of the concrete frame elements would have pushed this up further.

The finish of the concrete was another consideration. “We wanted to keep it quite raw and recreate the light industrial feel of the client’s current building,” says Scott.

What the contractor wanted to avoid was complex column construction. “The construction of any frame depends on being quick with the vertical elements because until they are in place the next floor plate cannot be cast, and a complicated column system could hold up the construction.”

Expanded came up with a simple solution. Rather than using column moulds and propping them at an angle, it decided instead to cast the columns using the same technique it would for a wall. Vertical front and back wall formwork shutters were put in position and internal shutters slotted in between them at the angle needed to create the column. The reinforcement was then placed and the concrete poured.

With this method it didn’t matter if the elements repeated or changed from floor to floor. “It was a much simpler system and it avoided the need for special moulds at the junctions where the columns come together,” says Scott. Another trick introduced by the contractor to speed up construction was the use of a post-tensioned slab, which cut down on large amounts of reinforcement steel and the time needed to fabricate it.

Treated plywood formwork was used to cast the floor slabs, with panels set out to a specific arrangement to coordinate with the column grid. Plywood shuttering for the columns was reused several times over, saving cost. The “as struck” finish will be left exposed everywhere except for the ceiling soffits: these are simply painted white to help daylight penetrate deep into the floor areas.

When the building is completed in May next year the diagrid will be wrapped in a double glazed curtain wall that will allow passers-by to glimpse the structure behind. “The building becomes more intriguing the closer you get to it and slowly becomes revealed,” says Allford. “The idea is that you know the structure is there and it becomes part of its identity.”

Topics

Specifier 19 October 2007

- 1

- 2

- 3

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Concrete lattice structures: How do you like my fishnet building?

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

No comments yet