Architects have been brainstorming with cost consultants to design out waste on live projects – and that’s been drumming up new ideas that could transform the industry by will Jones

Ustainability and waste reduction are indelibly linked and any practice that designs to sustainable principles should be looking to minimise waste in all aspects of the design, construction and operation of the buildings it creates,” says Alan Shingler, partner and head of sustainability at architect Sheppard Robson.

Waste management is an issue that Sheppard Robson tackles as part of its overall sustainability brief – a standard matrix that clients are asked to fill in at the start of every new project.

“It works as a guide to find out the level of aspiration on the part of the client,” says Shingler. “However, cost is always an issue and some preferable methods are not always employed because they are currently more expensive than the traditional construction route.”

Recycling and reusing construction materials is an approach that is gaining ground. It saves on resources, cuts waste and can save money. Meanwhile, exponents of offsite construction are proving that factory-built components and building modules are produced to higher standards than site-based methods and they perform to a higher level of efficiency once installed. This all makes a lot of sense, so why has it not become the norm?

“For modern methods of construction and waste minimisation to truly work you need to have full client understanding and buy-in,” says Shingler. “They have to want these new goals to be the driving force behind a project from the absolute outset. These things cannot be an afterthought.”

Turning the tide In early 2008 WRAP approached Sheppard Robson through Davis Langdon to take part in an exercise to design out waste in construction.

Estelle Herszenhorn, project manager at WRAP, explains: “WRAP identified that working with building designers would be beneficial to its goal of reducing waste in construction because that is where the initial decisions are made.

If we can influence the design to utilise less wasteful materials and methods, then the goal of halving construction waste to landfill by 2012 will be much more achievable.”

WRAP is seeking architects and schemes that it can work with to address the issue of designing out waste. Sheppard Robson and Foster + Partners have already become involved, and the firm will soon begin an alliance with Aedas.

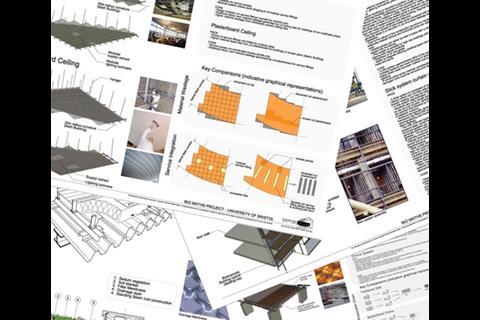

The exercise involves the cost consultant collaborating with architects on live projects to brainstorm the best materials, methods, products and systems to reduce waste at all points in the design and construction process, from component manufacture right through to operation of the building.

“The aim is to go in at the early stages of a project, ideally stage C or before, and engage the design team to see how we can reduce waste through good design,” says Herszenhorn . “Our goal is to produce exemplars that show how a project can be designed with less impact: less cost, less waste and a reduction in carbon footprint.”

University challenge

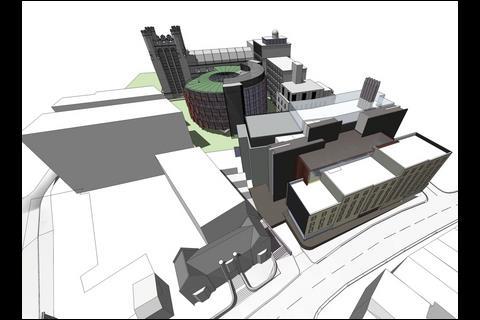

Sheppard Robson put forward two buildings on the same site for analysis – the new, 7,000m2 mathematics building and 12,000m2 biosciences building at the University of Bristol.

David Ola, Sheppard Robson project leader, says: “The exercise is really interesting. We are evaluating structural concrete flooring methods; the inclusion of a green roof; facade systems; and the effects of designing to regular plan form and standardised sizes, as opposed to non-plan form such as the circular maths building.”

The team has assessed the pros and cons of these elements of the design and come up with results that categorise methods as having a high or low impact on the project in terms of design, cost or other implications. For instance, unitised and stick systems of curtain walling were assessed. Stick systems are common and versatile as they can be used on all types of building, which makes for a competitive market, while unitised systems are less common and more complex and so could be more costly. However, stick systems require scaffolding for installation and this involves more time, labour and embodied energy than the quick mechanical installation of a unitised system.

“Our brainstorming was really beneficial,” says Alex Amato, associate at Davis Langdon, who facilitated the process. “There were obvious answers. For instance, the green roof did reduce the requirement for run-off drainage and the removal of waste, such as spoil, by not having to dig such big grey-water retention tanks. But it was more costly and time-consuming to install.

“Aspects such as designing to regular plan form revealed that ceiling and floor tiles should be designed as small grids rather than large because this produces fewer offcuts. And although that is of little consequence on a small job, it soon builds up to be a large waste factor on larger buildings.”

The process has thrown up good ideas for waste-saving measures. Sheppard Robson is in the process of reappraising its designs for the University of Bristol following initial consultation with the local planning authority. Together with the client, it is looking at integrating aspects of the waste management analysis findings.

Ola says: “The evaluation of waste trains the architect and the quantity surveyor to analyse the design in a different way. Traditionally, the QS has come at the project from a cost per metre squared approach. Now, if clients can see the savings that can be made through speed of construction, minimisation of waste or the reduction in requirements such as scaffolding, it will give the architect more licence to design innovatively.”

WRAP also used Davis Langdon’s work with Foster + Partners, which focuses on the medical sector. The practice is part of a framework of architects designing private hospitals for client Circle. Here, Amato explains, the waste study will focus on:

- The potential of different types of prefabricated bedroom units

- The rationalisation of design, best-practice installation and recycling of plasterboard

- Reuse of materials found on site, from replanting of trees to the reuse of spoil on site or as a viable commodity for other projects. Results are expected soon.

- Amato says Davis Langdon will draw on its work with these architects to promote better practice in four main areas of critical engagement:

- Reuse of construction products and materials created in the construction process, such as recycling steel frames or redirecting spoil.

- Designing for deconstruction and addressing the design life of buildings – “We want to encourage greater use of off-site manufacture,” says Amato.

- Dimensional consideration in design, which needs to be addressed to lessen material waste.

- A better understanding of where waste occurs, setting targets for its reduction.

The next steps

Industry has its work cut out helping clients and contractors, both large and small, to halve construction waste to landfill by 2012, but this move to address the problem in the early stages is a step in the right direction.

WRAP will publish guidelines based on the findings of the Davis Langdon work and, using case studies, it aims to have an impact throughout the industry. The initial intention is that public projects such as Building Schools for the Future and the NHS’s Procure 21 take the lead in implementing waste-reduction measures. PFI is another area where savings in both construction and building operation are paramount.

With the Olympics drawing near any means of reducing waste and minimising cost will be welcomed by the government and the London mayor.

Shingler sees this latest initiative as a new dawn in the fight to reduce waste in construction. “WRAP has traditionally worked with contractors on site. Now, by addressing the problem at the design stage, we are developing a truly holistic methodology. At Sheppard Robson we get involved in projects like this to learn how to better design buildings that are wholly more sustainable. But we also do it because, as a large practice, we have the responsibility to create and share knowledge with the industry. This work with WRAP is the foundation for real joined-up design on a large scale.”

Waste and the RIBA

“The RIBA supports the work of WRAP, which has a valuable contribution to make to the sustainable construction agenda. Construction generates over 100 million tonnes of waste each year and WRAP has produced guides and tools that are of use to building designers in seeking to actively address this issue,” says Adrian Dobson, RIBA director of practice.

“Of particular interest are its case studies on the maximisation of the use of recycled materials in various construction sectors and also its Net Waste Tool, which can greatly assist architects in advising clients on how they can meet their obligations under site waste management plans.”

Dobson also mentions the work of the technical task force, set up between the RIBA, BRE and Chartered Institute of Architectural Technologists. “The task force has been working to produce a detailed information sheet on site waste management plans and their implications for architects and clients. It should be available within the next few weeks.”

- For more information on the WRAP guides, including site waste management plans and the Net Waste Tool, go to: www.wrap.org.uk/construction

Weighing up the options: concrete mix

Sheppard Robson’s assessment of structural concrete floor construction at the University of Bristol identified the pros and cons of three options: traditional slab, BubbleDeck and the Omnia system:

Traditional slab

Pros

- Well-used, traditional form of construction

- Competitive, open market

Cons

- High cost in time and labour to erect temporary support and formwork

- Extra waste generated by use of temporary formwork and building materials

- Additional energy and logistics required to manage temporary building materials

BubbleDeck

Pros

- Less dead weight so increased strength per volume of concrete used (potentially longer spans)

- Less energy consumed in terms of production, transportation and installation

- No waste generation

- Speedier construction and better working environment

- Less labour required for precast formwork

- Overall cost savings

- Higher soffit quality achieved by using prefabricated units, allowing soffits to be exposed

- Less storage space because prefabricated

Cons

- Specialist construction technique and therefore limited competition and availability

- Consideration required for jointing in expressed soffits, which requires additional edge protection

- Co-ordination of joints

- Inflexibility in terms of localised dropped slab (on biosciences building)

Omnia system

Pros

- No waste generation and therefore less energy consumed compared with conventional methods

- Speedier construction and safer temporary working platform

- Less labour required for precast formwork

- Overall cost savings

- Higher soffit quality achieved by using prefabricated units, allowing soffits to be exposed

- Less storage space because prefabricated

- Off-site prefabrication allows easy accommodation of non-rectilinear or circular floorplates

Cons

- Specialist construction technique and therefore limited competition and availability

- Consideration required for jointing in expressed soffits, which requires additional edge protection

- Co-ordination of joints

- Inflexibility in terms of localised dropped slab (on biosciences building)

Postscript

This article previously appeared in the WRAP-sponsored supplement, “Halving Waste to Landfill: Are you Committed?”

Topics

The Wrap supplement 2008

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Drawing out waste: Architects have a special role to play in managing waste

- 10

- 11

No comments yet