A plan to build a Gehry-designed 'Museum of Tolerance' on the site of a Muslim cemetery in Jerusalem has led to an intercontinental war of words

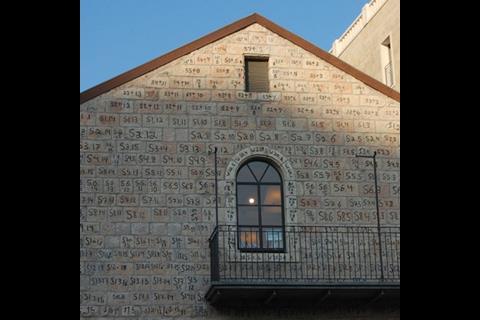

The Mamilla cemetery in west Jerusalem is not a beautiful place. Food wrappers and condoms are scattered across cracked paths and crumbling gravestones. Beneath them are the remains of thousands of Muslim soldiers, scholars and saints. Nobody has been buried here for more than a hundred years, but the battered stones commemorate a part of Jerusalem’s history that stretches back to the 13th century.

One corner of the cemetery is cut off by a corrugated iron wall topped with barbed wire and security cameras. It doesn’t look much like it, but this is a site hoarding around what is to be the Museum of Tolerance: a Jewish project on a sliver of Islamic history, which is provoking rows on three continents.

The building was commissioned by the Simon Wiesenthal Centre, one of the most influential Jewish groups in the West, named after an architectural engineer and Nazi-hunter who died in 2005. The Jerusalem centre was first mooted in 2002, and was intended to mirror the foundation’s museum in Los Angeles, whose goal is to promote religious tolerance.

Frank Gehry was commissioned to design the building, and the Municipality of Jerusalem allocated it a patch of land in the Mamilla cemetery. After quietly winning planning permission, work was about to begin when Muslim groups and Israeli moderates cottoned on to what was happening. The resulting row reached Israel’s Supreme Court, which decided last autumn that the building could go ahead. In November, work began on the excavation of human remains, but the arguments over the project are still in full flood: the latest development is the formation of a coalition of architects from around the world who are determined to stop the project.

Israel is a country where facts on the ground tend to turn into political (and physical) conflict. At a time when the conflict in Gaza has put relations between Israelis and Palestinians at a new low, could this be the worst time for such a project to start up?

White elephants and sacred cows

It’s not only Muslims that have a problem with the museum. “Have they even heard of irony?” says Shmuel Groag, an architect and town planner with Bimkom, an Israeli group dedicated to the resolution of conflict in Jerusalem. “What exactly is tolerant about this building? There is, as you know, a culture of intolerance in Jerusalem, and it is evidenced by this building.”

I meet Groag in a Jerusalem cafe a few blocks away from the site. He is scathing about Gehry’s design. “It’s monstrous. A white elephant. There’s no building culture like this here. This mishmash of materials, of shapes … it’s going to be awful.”

Groag was one of 15 signatories on a letter of protest sent to The Guardian in December. The letter, and a petition signed by architects such as Will Alsop and Sir Richard MacCormac, was the brainchild of Abe Hayeem, the London-based founder of a group called Architects and Planners for Justice in Palestine.

“This is the wrong building at the wrong place at the wrong time,” Groag says. “To pursue a building like this is highly insensitive at a time when Israeli intolerance to the Palestinians is at a critical level.”

Groag takes me to meet Professor Zvi Efrat, the head of architecture at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design. Efrat says the building’s scale and “brutal” design are problematic. “It’s a provocation, both in its designs and its intentions. It is anything but tolerant. It is positively intolerant.”

What this discussion underlines is that architecture in this city carries a freight of political and religious symbolism that it doesn’t elsewhere. This fact inspired the formation of a political group called Ir Amim (that is, City of Nations) which looks at the role of construction in the Arab–Israeli conflict. Haim Erlich, one of its experts, says architects and builders are being drafted into the battle whether they like it or not. “Construction is increasingly being used as a political tool here,” he says. “Planning and building seem very innocent and professional. But it is a high-powered political tool.”

Efrat believes Gehry had no idea of the minefield he walked into. “I think he wasn’t aware of the politics. He wouldn’t want to get involved in a mess like this. He’s a nice person.”

Gehry himself did not wish to contribute to this article. Instead, he issued a statement that said: “I believe in the urgent need for a peace that is just for both sides. I also believe the museum embodies the values of respect and compassion that have guided many faiths spanning Jerusalem’s 3,000 year history.”

Danny Seidemann, an Israeli property lawyer in his sixties, is co-ordinating the protests. He tells me the Museum of Tolerance, which can be seen from his office, is a cold sore on the face of the city. “This was all stupidity and naivete on behalf of the entrepreneurs,” he says.

To pursue a building like this is highly insensitive at a time when Israeli intolerance to the Palestinians is at a critical level

Shmuel Groag

“There was no malice on their part, wanting to build this thing here. The malice comes when you see how they’ve acted. They throw their weight around. They act like the provisional wing of the tolerance museum.”

What’s the problem? It was a car park

The Simon Wiesenthal Centre’s greatest sin, as Seidemann sees it, comes from ignoring the claims of the Waqf, the Islamic court in Jerusalem, which has ruled that the burial ground is sacred. “This has been a burial site since the 13th century. Why would it still be there if nobody thought it was sacred?”

I put this to Rabbi Marvin Hier, the co-founder of the Simon Wiesenthal Centre. Speaking over the telephone from California, he is adamant these claims hold no weight. His argument is that nobody has been buried in the Mamilla cemetary for more than 100 years, the site where the museum is being built was formerly a car park, and the Jerusalem municipality says it did not receive a single complaint about the building until after excavation started. “Not one complaint!” says Hier. “I would give legitimacy to these complaints if they were consistent, but they are not. There was an absolute lack of protest until it became politically convenient for there to be protest.”

According to the Simon Wiesenthal Centre, Islamic law says a cemetery loses its sanctity after 37 years. Several Israeli academics – and one Jordanian general – testified to the Supreme Court that this was the case. The land was declared absentee property in 1950, and it has been under the custodianship of the Jerusalem municipality ever since. “For years now this has not been a cemetery,” says Hier. “Muslim religion does not take the view that abandoned cemeteries must remain sacred. Only Hamas takes this view. Look at the cemetery. It’s a mess! Is that how you want to take care of your ancestors if you’re so concerned about them?”

I ask whether, with the cemetery being under Israeli administration, it might not have been so easy for Palestinians to have tended the graves themselves, far less stop it becoming a car park. “How much money would it take for the cemetery to look good? Two hundred thousand shekels? [£53,000] This could be done if they cared about it.”

I hazard, could he not see that building something like the Museum of Tolerance on a ground where Muslim graves still lie could itself be seen as a political act? “Excuse me, but that is not a respectful question,” says Hier. “We’re not the ones making this political. If we were not building a museum here, it would still be a car park.”

Protective walls

Yet Seidemann rejects suggestions that the cemetery should no longer be considered sacred. “Listen. Who are we as Israelis to tell the Muslims what is sacred? Sanctity has to be defined by the consciousness of a community. Maybe it was the sight of human remains being taken out that got people thinking maybe this shouldn’t be happening.”

Seidemann has now joined forces with Ir-Amim to lobby the Israeli establishment against the construction of the museum. It is a time of change in Jerusalem. The new mayor is a secularist, and it is understood that he is to “review” the museum. Israel will hold a general election on 10 February, and this, too, could affect the project.

If there’s one thing on which Seidemann and Hier agree, it is that the museum has caught the attention of fanatics. “There are people who will abuse this issue,” warns Seidemann. “It has been adapted by the northern wing of the Islamic party, who are hardliners. My worry is that the museum is strengthening the voice of radical Islam, which is not what a Museum of Tolerance should be doing.”

For now, Seidemann’s only hope is with the credit crunch. Hier admits there isn’t enough money to complete the museum for another four-and-a-half years. “We’re 50% there, but it’s going to take a little longer than we thought, is all. We’re moving forward,” he says.

Meanwhile, the forbidding fence around the site remains in place. The project broke ground weeks before Israel’s invasion of the Gaza Strip. The conflict is in full swing while I am there, but it is noticeable how little people are talking about it. Groag, though, says events in Gaza have dark implications for the fragile balance of the city, and this can only inflame tensions around the Museum of Tolerance.

“It’s a very tense city, Jerusalem,” he says. “There is tension in the streets. Palestinians and Israelis have built a kind of emotional wall between themselves so they can live alongside each other. What is going on in Gaza and what is going on with this museum are similar, in one way. They have the potential to break down that wall.”

Why did Gehry take the work?

The architectural critic Charles Jencks was one of the signatories of a British petition against Gehry’s Museum, even though he counts the architect as one of his closest friends. He speaks about how architects like Gehry get involved in such projects.

It is the law of increasing guilt. People go along with things without realising they are digging a hole for themselves. If you put a frog in boiling water it will jump right out, but if you put it in cold water and slowly turn up the heat, it will boil to death. You have to be sensitive to events, and this is not what architects do. Architecture is what architects do. They are not committed to politics. Frank thought that this was morally okay. He got in, and as far as he was aware the site had been cleared of any problems.

Imagine if Frank walked away from this project. He couldn’t. He is legally bound to it, but also professionally bound. He would destroy his credibility with the Jewish community of which he is a member; he would jeopardise his practice, he would draw the anathema of his Jewish friends and colleagues, and Jewish developers from coast to coast.

How to win politically safe work in Israel

Although you may not want to get involved in the construction of buildings in Muslim graveyards, there are potential opportunities in Israel that are less controversial.

Bayti Real Estate, a joint venture between Qatari Diar and Palestinian developer Massar International, is dedicated to building Rawabi, a $350m (£250m) town for 40,000 Palestinians near the city of Ramallah in the north of the West Bank.

The first phase of Rawabi is expected to go on site later this year, and firms including Faber Maunsell and EDAW are already working on it. Later phases are going to need project managers, environmental consultants and architects. The project is being developed in co-operation with the Israeli authorities, so you shouldn’t worry about political problems.

The task of rebuilding Palestinian homes destroyed by the recent conflict in Gaza is less simple, and considerably more political. Although the Palestinians say that more than 4,000 homes were destroyed in the fighting, the importation of building materials is severely restricted by the Israeli authorities. There are about £1.4bn of repairs to the infrastructure to be done. Scores of schools, mosques and factories were devastated in the conflict, and major repairs are needed to power and water facilities.

The UN has pledged to raise $613m (£430m) for the rebuilding effort. Several British companies, including Arup, Atkins and Sheppard Robson and US firm Parsons Brinckerhoff are on the list of approved contractors for the UN.

If the Israeli construction market is too controversial for you, then it worth thinking about neighbouring Lebanon, which is in the middle of a construction boom. Building activity in the country rose by 30% in the first 10 months of 2008.

Postscript

Original print headline: 'The museum of irony: Gehry's Museum of Tolerance'

No comments yet