With booming economies and rapid population growth, South-east Asia is on the UK government’s radar – but are British construction companies too late to the party?

In February, international trade secretary Liam Fox gave a speech at the headquarters of media giant Bloomberg in London spelling out his ambitions for UK trade after the country leaves the EU next March. Fox told his audience about the potential for trade with countries in distant corners of the globe, noting in particular the thriving economies of South-east Asia. Their prosperity could drive demand for goods and services from those that venture there, he said.

Fox clearly has a vested interest in talking up the UK’s trading credentials, particularly since the government is struggling to persuade MPs and the business community that it knows what it’s doing over Brexit. Last month, Eurotunnel director John Keefe was reported as saying that without knowing what a “no deal” scenario would look like, his company “can’t build infrastructure, can’t recruit people, can’t specify systems – we can’t construct anything”. Against this background, Theresa May’s government has to find a way to tell a positive tale – opportunities in South-east Asia fit that bill.

“The days of jetting in somewhere to show them how it’s done are long gone”

Ann Bentley, Rider Levett Bucknall

To date, the surrounding region – South and East Asia – has been a goldmine for UK firms, with its booming economies, rapid population growth and demand for better standards of living fuelling investment in infrastructure and new housing. With the government suggesting that Brexit will free up the UK’s trading potential, ministers are throwing their departmental weight behind sectors such as construction – including designers and consultants – to explore similar opportunities elsewhere.

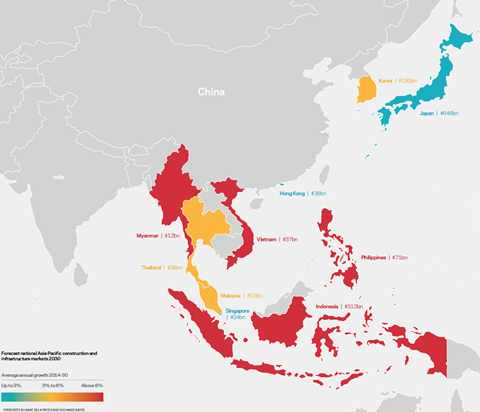

Specifically, they are eyeing up the region covered by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), which has 10 member states, an area of 4,46 million km² and a population of 650 million. Within that area, there are significant differences – for example, Vietnam and Myanmar are small but growing, while regional behemoth Indonesia has been booming for a while, offering a diverse set of opportunities. But the region’s construction sector is already competitive and, as these nations grow, so is the local expertise.

So can Fox and his colleagues at the Department for International Trade help construction companies to unlock the potential of these markets, or is the UK government being overly ambitious in seeking to exploit growth in this region?

Infrastructure opportunities

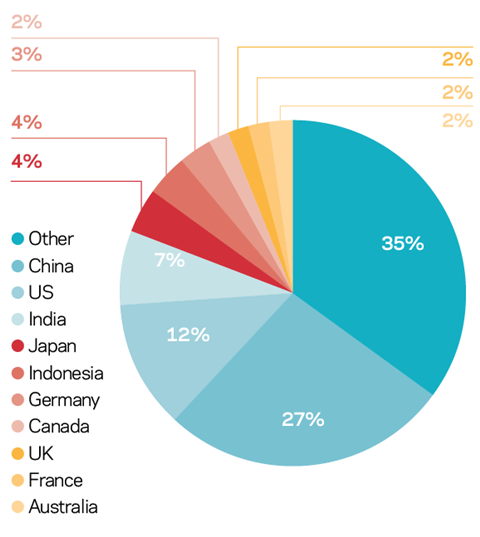

UK construction companies have long viewed South-east and East Asia as markets where money can be made. Architects, engineers and consultants have worked in the region for decades, designing office blocks, transport hubs, residential towers and more. As populations and economies in these countries grow, demand for infrastructure, workspace and homes will increase – according to research group Global Construction Perspectives, by 2030 four of the world’s top five construction and infrastructure markets will be in Asia: China (first), India (third), Japan (fourth) and Indonesia (fifth).

Indonesia, the largest of the ASEAN economies by GDP, is expected to see phenomenal growth, according to Graham Robinson, director at Global Construction Perspectives. The country has huge growth potential, he says, “turbo-charged” by a series of factors. “A growing population, lots of young working people; it’s resource-rich, plus it has a big infrastructure deficit. There is a huge need to build in all areas.” Plus, as China becomes more expensive, Indonesia is attracting companies looking for places to manufacture their products.

But the case of Malaysia, another big player in the region, is a warning that working in South-east Asia can also bring uncertainty –

the country seemed to be on the brink of a construction boom, but the new government is reported to have pulled the plug on a number of billion-dollar projects, citing the need to slash the national debt. Local reports suggest that, as part of a series of austerity measures, newly elected prime minister Mahathir Mohamad has been looking to get out of obligations to pay for schemes started by his predecessor Najib Razak, including a Kuala Lumpur-to-Singapore high-speed rail link and an east coast rail scheme.

For Andrew Hodgson, consultant Atkins Acuity’s director for transport in the Asia-Pacific, the recent announcements in Malaysia highlight the need to develop a clear business case when proposing infrastructure investment. “South-east Asia has a diverse mix of economies tackling a range of challenges, but a single thread links them – a need for infrastructure investment to support economic growth. The opportunity lies in developing investment-grade projects that are technically feasible and deliver economic benefits. We see this as an increasing trend [across the region], and [it] has clear potential to achieve better value for money over time.”

Jonathan Beard, head of business advisory, transportation and logistics in Asia for consultant Arcadis, says getting closer and developing an understanding of clients and customers – the end-users for buildings and infrastructure – is increasingly important in order to better grasp the dynamics of the region. “The recent change of Malaysian government and the reassessment or cancellation of several major projects is a salutary reminder of how workstreams can suddenly be halted,” he says.

UK Export Finance’s role

The UK government says it can offer support to firms looking to do business in South-east Asia. A spokesperson for the Department for International Trade (DIT) said: “The department offers a wide range of support for all British businesses seeking to enter the Asia-Pacific market. This includes our award-winning export credit agency UK Export Finance [UKEF], a range of export opportunities on [one of our websites] great.gov.uk and our overseas network, who are on hand to provide specialist regional knowledge where necessary.

“Through UK Export Finance, the UK’s export credit agency, we can offer government-backed finance and insurance to help companies in the construction sector win, fulfil and get paid for export contracts. UKEF has significant capacity to support exports to South-east Asia, and can offer financing to buyers in the region in a range of local currencies including Malaysian ringgit, Singaporean dollars, Indonesian rupiah and Vietnamese dong.

“As well as on-the-ground trade support, DIT has appointed a network of export finance specialists to be based across key overseas markets. The first to be appointed, in February this year, is based in Indonesia.”

Breaking into markets

The UK government may lag behind the US and many other European countries in its efforts to support its businesses abroad, but Robinson believes it’s finally waking up. “Traditionally many UK consultants have secured work by being determined, and over the past few years there has been little in the way of support from the UK government. But lately we’ve seen more backing, notably on higher-value projects. The question is: is it too late?”

The government is at pains to stress it can “offer government-backed finance and insurance to help companies in the construction sector win, fulfil and get paid for export contracts”. Some of this activity is being channelled through bodies such as Infrastructure Exports: UK (IE:UK), which features a number of UK construction bigwigs on its board, including Bam Nuttall executive director Martin Bellamy, Atkins’ UK and Europe chief executive Philip Hoare, Arup’s global infrastructure lead Peter Chamley and James Wates of Wates Group, its co-chair (see “UK export finance’s role”, top right). In its own words, IE:UK “brings together companies of all sizes as a single ‘Team UK’ consortia to bid for global infrastructure contracts and deliver complex projects by combining their expertise”.

Bellamy says its activities, which include underwriting loans for development schemes, remove a degree of risk. He adds that British expertise is still highly regarded “but it comes down to financial viability”, arguing that China and Japan are already ahead, selling design, construction and finance for projects in a one-stop package. Ann Bentley, global director of consultant Rider Levett Bucknall, agrees – governments that are building large schemes want a complete package that’s fully costed, she says.

Given the intense competition – and the sometimes complicated practicalities of working in some South-east Asian markets – UK firms often opt to work with a local partner or open a satellite office. For example, London-based architect Heatherwick Studio joined US practice Kohn Pedersen Fox’s design team, working with Singaporean firm Architects 61, to win the design job for one of the world’s biggest air terminals at the Jewel Changi airport in Singapore.

A little local knowledge goes a long way, according to Bentley – particularly in countries where you are expected to speak the language. Working with a local firm helps with that, as well as bringing contextual expertise. “The days of simply jumping on a plane and jetting in somewhere to show them how it’s done are long gone,” says Bentley. Indeed, the skills levels in the region are rapidly overtaking those in the UK – and British professionals are also likely to face competition from neighbouring regions. Bentley points to the fact that India is producing more engineering graduates every year than the UK as a sign of things to come in Asia.

Some South-east Asian countries, such as Vietnam, may be relatively poor – its GDP is $202.6bn, compared with Indonesia’s $932.2bn – but they all harbour ambitions to grow. In Vietnam’s case, 2017 saw the fastest annual GDP expansion in a decade. In such markets, there will be demand for both local and international expertise for a while. The trade secretary will be hoping UK firms can harness that potential and, in the process, fulfil his post-Brexit vision for a “global Britain” after March next year.

No comments yet