Our industry now has a plethora of initiatives to encourage us to build sustainably, either through sanctions or incentives. Has the government has got the balance right?

By now the construction industry has a good idea of why it makes sense to help the UK hit sustainability and energy efficiency targets. There’s legislation, client and planner demand, tax breaks, and a sense of social responsibility, to name a few. And then there’s shame: “To be known as a portfolio holder of the most environmentally damaging buildings in the UK is not the best place to be for any private or public organisation,” says Rick Willmott, chief executive of contractor Willmott Dixon. “It’s a very powerful driver, embarrassment.”

But with ambitious targets flying at firms left, right and centre - a 34% cut in the UK’s carbon emissions by 2020, 80% by 2050, 15% of UK energy to come from renewable sources by the same date - construction firms have their work cut out. And the concern is that as the government tries to claw back funds the balance is moving away from rewards and towards punishments.

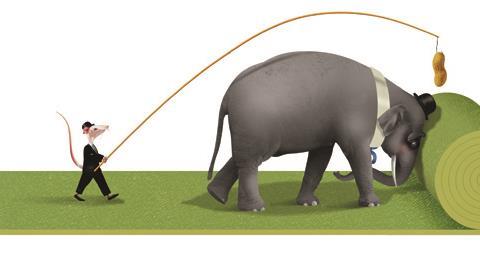

Craig Sparrow, head of Skanska’s UK green business, explains: “Legislation has a very important place in driving energy efficiency within the built environment but we [the construction industry] have got to be incentivised to want to make some of these improvements of our own accord without just getting hit by a big stick.”

Andrew Warren, director of the Association for the Conservation of Energy, says the best initiatives strike a three-way balance: “If you want a really effective energy saving policy, it has to have a balance of carrots, sticks and tambourines: incentives, things that will be damaging to you if you don’t do them and things that attract attention. The best initiatives have a good balance of all three.”

So how far does this hold true of the government’s biggest green initiatives? In the month the government announced the main details of its Renewable Heat Incentive and the revised feed-in tariffs, we give a rundown of the seven key sustainability policies and weigh up how much there is to gain and how much to fear when it comes to compliance.

Renewable Heat Incentive

Earlier this month it was announced that the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) has £860m set aside for technologies such as biomass boilers, ground-source heat pumps, thermal solar panels, and bio-methane projects, which use organisms to break down organic waste to produce the gas. From July this year, non-domestic buildings will earn a tariff for heat created from these sources, which will come in for homes a year later.

Richard Quartermaine, a sustainability associate from Cyril Sweett, says on large new-build projects like schools or hospitals the RHI will boost the number of solar thermal panels, for example, but it doesn’t mean they will replace PV cells. “It makes [solar thermal] more viable, but it isn’t enough to change technologies,” he says. Homes will have to reach certain energy efficiency standards to get the RHI. Non-domestic buildings, however, will not.

With the existing stock, the RHI should make it viable to install renewable sources at no upfront cost, and recoup the investment from the tariffs, says Matt Fulford, director of sustainability at EC Harris. Yet this market will take a little while to emerge, he thinks. “A lot of people haven’t picked up on the RHI yet. It’s going to take 6-9 months before we get up to speed.”

Carrots: 3 (out of 5)

Sticks: 0

Feed-in Tariffs

These have been around since April 2010, and subsidise every kilowatt of power produced by clean electricity sources such as solar panels and wind turbines. A pot of £360m is available and, as with the RHI, the intention is to reduce the amount of subsidy as the technology catches on and economies of scale are achieved. Up to now the uptake has exceeded all expectations, and companies such as Beco, now owned by Kier, have planned dozens of large solar arrays on schools, offices and social housing projects.

But last week’s review of the feed-in tariff slashed payment levels to schemes over 50 kW by up to 70%, rendering them unviable. The government says the reductions are designed to prevent large-scale “solar farms” from diverting money from homeowners and small businesses.

Dan Phillips, a sustainability director at Buro Happold, still thinks the subsidies mean solar or wind power can be embedded cost-effectively into a lot of small and medium new build: “We are advising our clients to make use of FITs and to incorporate renewable power into their designs.”

However Matt Fulford, director of sustainability at EC Harris, isn’t so sure that FITs (or, for that matter, the RHI) are actually the main force behind renewable technologies on new buildings. “The driver is still going to be planning conditions and Part L,” he says. “The FITs and RHI might take some of the pain away but it’s not the main driver.”

Carrots: 4

Sticks: 0

Zero carbon

This is the biggest and most complex of all the government’s sustainability objectives. The goal is to make all domestic and commercial new builds zero carbon by 2016 and 2019 respectively, and Part L in the Building Regs is the main mechanism to achieve that target.

But the widespread opinion across industry is that these targets are unachievable in the timeframe. Barratt boss Mark Clare said in March that he did not expect housebuilders to reach the homes targets until 2018.

Wednesday’s Budget announcement that emissions from appliances in the home are no longer part of zero carbon will help relieve some of the pain for housebuilders. But this was going to be done using more efficient offsite sources of energy rather than expensive onsite renewables so won’t save them much money.

All in all there is hardly an air of encouragement surrounding zero carbon at the moment.

Carrots: 0

Sticks: 5

CRC Energy Efficiency Scheme

Formerly known as the Carbon Reduction Commitment, this incentive, which is a mandatory cap and trade scheme applying to large non-energy intensive organisations in the public and private sectors, has seen its carrot rating decrease hugely in the recession. Before last autumn’s Comprehensive Spending Review, the initiative worked by recycling revenue to participants according to performance. Now it will work more like a traditional tax as carbon allowances must be bought from the government, which will retain all of the revenue generated. It is expected that the Treasury will raise about £3.5bn over the first three years of the scheme.

The CRC could be a fantastic watershed towards the industry looking more closely at occupying costs

Nick Katz, Colliers

This obviously means the construction industry won’t be gaining as much by adhering to the initiative as in the past. There is some good news, though. Participants have been given a budget by the government to spend on energy efficiency measures in 2011 - but they need to move fast. If they don’t take the opportunity to implement effective energy saving measures before 2012, they are likely to have to pay a hugely increased price. So the incentive is there - but very much in stick, rather than carrot, form.

Nick Katz, senior sustainability adviser at commercial real estate group Colliers, has some advice for firms looking to make the most of their 12-month grace period. “Forget spreadsheets,” he says. “Get sorted with a software platform to get a proper insight into what your properties are doing. And benchmark internally. If you can make your least efficient assets more efficient, that will have a hugely positive effect.” He adds that, despite causing some headaches for the construction industry, on a wider scale the CRC could be an important game changer when it comes to energy efficiency and sustainability in the UK. “The CRC could be a fantastic watershed towards the industry looking more closely at occupying costs and has the potential to create a global example of how these issues should be dealt with. But if you are not thinking ahead on this, you will get left behind. Pull together the right people now, your CFO, and environmental expert, consultants, someone with a legal background and start talking about how to take things forward.”

Carrots: 0

Sticks: 2

Green Deal

The Green Deal is a finance package that would allow homeowners and businesses to improve the energy efficiency of their homes at no upfront cost and then repay the loan through savings on their energy bills. If it works, the Green Deal could create an ocean of work for firms - and up to 250,000 jobs, according to the government - as all 26 million homes and non-domestic properties are upgraded from autumn 2012.

The industry is generally unsure of how big an opportunity the Green Deal will be because the government is yet to release detailed targets or say exactly how homeowners will be encouraged to retrofit their homes. Minimum energy efficiency standards for houses would make the deal a much more real market for the industry but the government has said it would rather not regulate private homes, at least to begin with.

The rented accommodation market could be more promising, as the proposals allow tenants to force landlords to make energy efficiency improvements.

There could be lots of work for surveyors. “There needs to be work done, plus costing and analysis of whether what people install will actually deliver the savings proposed,” says Richard Quartermaine, a sustainability associate from Cyril Sweett.

Carrots: 2

Sticks: 1

Planning

Planners can demand a whole raft of measures over and above Building Regs as a condition of planning. The Merton Rule, for example, brought in by Merton council, requires 10% of a building’s energy needs to be generated from on-site renewable sources. Other boroughs now routinely require 10-20% from on-site renewables.

Requirements have now become a post code lottery, subject to the whims of the local planning department. In theory this could get even worse with localism although there are proposals to bundle the raft of local requirements into defined packages. The idea is that councils could choose from this menu, which would tick the localism box while ensuring consistency across the UK.

John Tebbit, industry affairs director at the Construction Products Association, says: “We are not getting the benefits we could be getting as everyone is asking for different things. The industry is frustrated and the planners aren’t getting the level of sustainability they want. So it’s lose-lose.”

He says that, to drive sustainability, planners must better communicate with industry: “It’s down to planners to come to industry and develop a common language because the industry is really suffering as a result of this not happening.”

Carrots: 0

Sticks: 4

Display Energy Certificates and Energy Performance certificates

Energy Performance Certificates (EPC) work out how homes can reduce carbon dioxide emissions and be more energy efficient. The higher the rating, the more efficient the building. The newer Display Energy Certificates (DEC), currently used in all public buildings over 1,000m2, are based on the actual energy usage of a building and increase transparency about the energy efficiency of public buildings. The incentive behind these initiatives is that they add value to a building, making it more popular with the client, landlord and occupiers.

DECs are considered by many industry professionals to be a more effective tool to show the performance of a building as the ratings given are based on energy bills from the building, which accurately show how it has performed.

Everyone should have to use decs, especially in banks and hotels, so people can see exactly how they are performing

Andrew Warren, ACE

This indicates not only how a building is performing in any given year, but compares it to previous ratings. This is in contrast to simply predicting how a building might perform theoretically, which is how EPCs work.

Craig Sparrow, head of UK green business at Skanska, says: “EPCs do allow you to categorise your building, but they are not something the industry is wholeheartedly behind as we wonder whether we should be using metrics that are harder on the energy performance of the building. That would be a real incentive.”

And that’s where DECs some in - especially as there are proposals to roll these out to all commercial buildings within 18 months. For firms ready to embrace it, there could be benefits in terms of impressing clients and being in a better position to help them reach sustainability targets.

Andrew Warren, director of the Association for the Conservation of Energy, highlights just how important the mandatory element of the proposal is: “If it is done as a voluntary measure you’ll end up in a situation where A-rated buildings stick up their certificates with pride and G-rated buildings keep very quiet. It should be that everyone has to do it, especially in buildings like banks and hotels so people can see exactly how they are performing. It is naming and shaming, but it’s also naming and praising, which is a good balance.”

No comments yet