UK construction has a patchy record in delivering major commercial projects on time and budget, and the challenges will only increase in the face of global uncertainties and risk. Steve Watts of Turner & Townsend Alinea explains past and present initiatives to tackle this, including innovative new procurement systems

01 / Introduction

The world is rapidly changing, and real estate needs to be agile to adapt to different demands and constraints – and, more than anything, uncertainty.

The UK construction industry has shown it can adjust to changing circumstances, yet consistent commercial success on major projects remains elusive: large public project failures are just the tip of the iceberg. It is not just sponsors and clients that suffer: contractors can be dramatically affected by poorly performing projects, as reflected by recent administrations. This has been the situation for decades, but recent shocks and persistent instability have exacerbated the risks in development and construction for all involved. We are faced with historically high construction costs and a high-risk, uncertain environment. What part does procurement play in this.

02 / Stretched viabilities and heightened risks for the sector

“Uncertainty and volatility have become fixtures of the geopolitical landscape, with rapidly evolving US policy as an animating force,” and globalisation is being “rewired”, according to Blackrock’s latest Geopolitical Risk Dashboard (July 2025).

Its top risks included: global trade protectionism; Middle East regional war and other conflicts; US-China strategic competition; global technology decoupling; major cyber-attacks; and European fragmentation. That is a lot to worry about, yet the report points out that even with such uncertainty and risks, “markets have proven agile, adaptive and resilient”. Perhaps we really are getting used to expecting the unexpected.

For construction, this creates an almost perfect storm of conspiring reasons why investment managers are struggling to get schemes to stack up, encouraging a wait-and-see approach, with projects moving more slowly through each stage:

- Global volatility has damaged confidence and skewed traditional asset returns.

- Interest rates have moved to a higher level.

- Economies around the world have stagnated, with structural changes such as ageing populations weakening demand and shrinking the labour force.

- Construction costs have been rebased to a much higher level, and inflationary pressures continue.

- The supply chain is ever more cautious, consolidating its workload in the face of heightened risks, financial fragility and skills shortages.

- Tenant demand is more nuanced, requiring higher-quality, more flexible buildings that are attractive to their hybrid workforces.

- Extensive regulation has changed the product and, in the case of the Building Safety Act 2022 particularly, the process too.

In other words, both the supply and demand sides of construction purchasing are fragile and fraught with uncertainties. Meanwhile tenants are struggling with the same headwinds and are attempting to optimise their real estate to support their businesses in an era of high costs and uncertainty.

03 / The challenges of large London projects

Large, tall, complex commercial projects in London are the sort of major projects that have been the subject of extensive work by Bent Flyvbjerg, whose 2023 book How Big Things Get Done revealed the scale of the problem. He and his team created a database of around 16,000 mega-projects to understand, applying econometrics, why projects succeeded or failed. Of all these projects, only 8.5% achieved time and cost targets, and only 0.5% (80 out of 16,000) hit the mark on time, cost and quality. Recent research by Mace echoes these results, highlighting how mega-projects often face delays or cancellations.

Current market, political and regulatory dynamics are making commercial development even more difficult. This means it is vital that teams take control of what they can, setting up projects and procurement strategies for success, as an industry that has historically found it difficult to get projects in on time and budget faces heightened risks and constraints.

London is one of the most expensive places in the world to build, as noted by the 2025 Turner & Townsend Global Construction Market Intelligence report, and the most expensive place in the world to fit out offices, as noted by the Turner & Townsend Global Fit-out Cost Index. This is why the UK capital is the most expensive place in the world to occupy an office (Savills Impacts Report, issue 8, 2025).

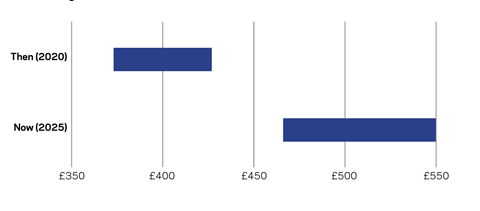

Larger, more complex projects have been particularly affected by global shocks and constraints due to the scale and nature of their materials and components, their wider global supply chains and their longer programmes. This is demonstrated by a comparison of London commercial office tower costs between five years ago and now (see diagram below).

Figure 1: London office towers, shell and core construction cost, excluding outliers (£/ft² GIA)

Viabilities may be stretched but there is pent-up demand for prime offices, due to a lack of high-quality offices set to be delivered over the next five years, and the best, most sustainable spaces can attract a significant rental premium. However, costs, risks, uncertainty and low confidence are making developers cautious, with projects pausing or moving more slowly.

Creating certainty and clarity through the set-up and procurement phases could encourage the pipeline of tall and large projects. Attempts have been made over the last 30 years to do exactly this.

04 / Past government and industry initiatives to improve construction performance

The 1994 Latham report was commissioned by the government to address the systemic issues of adversarial practices, fragmentation, inefficiency and a lack of respect for employees – recognising frequent cost overruns and delays across the sector. Its recommendations covered partnering and collaboration, client focus, standardised contracts (promoting the NEC form) and training and development.

The 1998 Egan report recommended bringing the supply chain together, with committed leadership that sets clear goals and a culture to improve efficiency and quality in the construction industry.

In 2009 a review of progress against the recommendations of these two reports was chaired by Andrew Wolstenholme. It concluded that some recommended practices had been adopted, particularly on high-profile projects, but that implementation was not as widespread as had been hoped. Its own recommendations ran along similar themes to the previous reports.

>>Also read: Cost model: Building the good manufacturing practice facilities the UK science sector needs

>>Also read: Slowly does it: where is this elusive growth for construction?

The turn of the century brought PPC 2000 (Project Partnering Contract 2000), designed to facilitate collaborative working on construction projects, under terms that are built on trust and fairness, avoiding conflicts (and with specific obligations for value engineering and risk management).

Although PPC 2000 (and its later updates) has been used on certain large and complex projects, it is not widely used, certainly in the commercial sector, because of its complexity and the time needed to establish partnering relationships, together with the discomfort of its heavier reliance on trust and collaboration.

While it appears the impacts of these, and other, initiatives have been less than what might have been hoped, there have been successes in construction, especially in the face of adversity.

05 / More recent initiatives to improve construction performance

Irrespective of procurement routes, the difference between project delivery success and failure often comes down to doing the simple things well: setting up a project correctly with an understood and aligned set of objectives that are developed into a clear brief, with the project team encouraged to work collaboratively.

Bent Flyvbjerg’s How Big Things Get Done contains a set of recommendations that are driven from his research and investigations, which are distilled into seven recommendations (see figure 2, below).

Figure 2: Bent Flyvbjerg’s research-driven recommendations for success on big projects

| Action | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Start with why | Focus on the ultimate goal, with a clear understanding of the what and why of the project, and never lose sight of it |

| Think slow, act fast | Ignore pressures to start in haste and instead plan thoroughly, building a solid, tested foundation – then move quickly into the execution phase (”Projects often don’t go wrong so much as they start wrong,” says Flyvbjerg) |

| Don’t fall victim to cognitive bias | We tend to underestimate risks and overlook external factors, leading to so-called watermelon projects – green on the outside, red on the inside! |

| A robust planning process | Go beyond desktop planning to test your assumptions in real-world scenarios, building prototypes, iterating regularly and solving problems during the planning phase, when the stakes are much lower |

| Reference class forecasting | Use relevant databases including lessons learnt; this data must include so-called black swans (unpredictable, rare occurrences that have a massive impact). To exclude such events from the analysis is mere hubris |

| Use an experienced team | Get the right people and put them in the right roles, with a core team of deep expertise and a proven track record |

| Modularity | The concept behind Lego is brilliant – apply it wherever possible to construct large, complex systems from small, manageable pieces. Flyvbjerg’s research shows that modular projects are less prone to disaster, thanks to their scalability, flexibility, resilience and efficiency |

Trust and Productivity: The Private Sector Construction Playbook, from the Construction Productivity Taskforce, promotes all these principles, creating a comprehensive guide to effective procurement. On top of a set of non-negotiable priorities that focus on safety, wellbeing, sustainability and value to society, it sets out 10 drivers (see figure 3, right) for success which, in terms of procurement, focus on early supply chain engagement to improve carbon, costs, quality, risk transfer and flexibility.

Figure 3: Trust and Productivity proposes 10 drivers for success to underpin projects

This early engagement is founded on agreeing contract terms and conditions at the outset as well as a framework of commitment gateways that ensure progress is being successfully made before proceeding to the next stage.

Success includes achieving agreed commercial and carbon targets. It also aims for greater clarity and transparency in the business plan and acknowledgment of what success looks like at the beginning.

06 / Lessons learnt from managing projects during a crisis

During the covid-19 pandemic, construction was forced to change. A report by Loughborough University (published in August 2020) demonstrated that improved planning and work sequencing that made sites secure, safe and tidy also improved efficiency.

Reduced layering of management and bureaucracy enabled decisions to be made more quickly and risk management to be implemented without delays. Productivity improved significantly. Better planning and better ways of working meant that only 7.5 people would be needed to do the work traditionally done by 10 people.

Some four years later, the war in Ukraine brought supply chain disruption and price shocks, which exacerbated the latent pressures from Brexit and the pandemic. Clients and contractors struggled to equitably address future material price increases or delays.

Greater communication of pressure points and project value drivers enabled contractors to find new sources of materials, alter supply chains and employ new tactics in buying, transporting and storing materials.

Much has been written before and since on how to remove inefficiency in the industry, but it can take a crisis or two to show what can really be done.

Sustainability

The events and challenges of the last five years or so have also revealed the complexity and fragility of supply chains and allowed us to assess them in more granular detail. Lessons learnt include:

- A more detailed understanding of the components of pricing through the supply chain

- How and where components are made and transported, which would provide better knowledge around carbon footprints

- Where contractual and quality responsibilities lie

- The ethical aspects of procurement, bearing in mind that many firms must make a statement about what steps they are taking in respect of the Modern Slavery Act.

Examples of this approach include sustainable procurement whereby Turner & Townsend aids in enhancing ESG in companies’ operations through a data-led method to measure, engage and manage the supply chain. Typically, around 70% of an organisation’s carbon emissions sits across its supply chain, and legislation increasingly emphasises outcomes that sustainable procurement can address.

At a recent project for Heathrow Airport, this approach has led to the development of a balanced scorecard for supplier performance. After assessing suppliers’ capabilities, the scorecard is integrated into the tender cycle, providing valuable data and intelligence. Considerable progress has been made, with suppliers aligning to Heathrow’s sustainability strategy, evident in improvements in metrics such as carbon reporting, sustainable aviation fuels, and zero emissions vehicles.

07 / Current procurement routes for major London commercial projects

Clearly, the industry has endured chronic sub-optimal performance and yet has shown that it can respond impressively to severe challenges. How has this played out in the way we procure major commercial projects in London? The choice of procurement route usually boils down to two-stage design and build or else construction management.

Under a two-stage design and build contract, a main contractor provides a fixed-price lump sum, taking responsibility for cost and programme, and design, with all trades sitting as subcontractors. The relative certainty of a fixed-price and commercial wrap comes with a potentially higher price through the layering of margins and risk premiums. The level of fixity at contract-sum stage will depend on the quantum of provisional sums and the robustness of the design.

Construction management, with its integration of design and construction offering programme advantages and the potential for overall cost savings due to shorter timelines and direct relationships with trades (which also allows for better client control), has proven effective for large and complex projects. However, it requires the right team in an appropriate environment, along with a client possessing relevant experience and resources. Moreover, it does not provide the cost and schedule certainty that funders crave.

The list of general pros and cons in figure 4 below shows that neither procurement route is perfect, but a fixed-price two-stage design and build approach remains the prominent route largely because the market prefers a single point of responsibility for risk, for completing the design, for warranties and for a lump-sum price.

On some projects, works packages have been added to the main contractor’s first-stage tender to secure a higher percentage of fixity, but this tends to be where the schemes are more straightforward with repetitive structures and simple substructures. The extent to which any package tendering is included in the first-stage tender will depend on the precise timing of the main contractor engagement as well as design maturity.

Current strategies aim to combine some advantages of a fixed price with a construction management approach, by targeting an early start on site but with progressive cost fixity leading to an ultimate fixed price. These strategies increasingly rely on the earlier, more targeted involvement of specialised trade contractors to ensure that the design is developed efficiently and is buildable, while also providing earlier cost certainty, thereby reducing the inherent commercial risks associated with a two-stage design and build contract.

Controls are implemented to safeguard the commercial position and manage risk, so clear budgets and cost plans should be established early on and managed through a change control process. This earlier meaningful engagement would entail earlier financial commitments.

Both two-stage design and build and construction management can be effectively used, and recent developments to combine the best of both routes have improved the process and the commercials by bringing more of the wider team together earlier. Some newer initiatives from other sectors have also been put forward to address the wider issues of trust and responsibility. These continue to be developed for the commercial market.

Figure 4: Summary of pros and cons of the two current main procurement routes on large London commercial schemes

| Fixed-price design and build (two-stage) | Construction management | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| √ | Fixed price obtained at stage 2 | √ | Overlaps design and construction, allowing a quicker start on site |

| √ | Single point of responsibility for design and construction | √ | Direct influence over subcontractors gives scope for better prices and value engineering/buildability advice |

| √ | Buildability, programming and planning advice obtained from main contractor in first stage | √ | Breaks down traditional adversarial barriers |

| √ | Client need not commit until design is substantially completed | √ | Provides flexibility to accommodate changes and deal with complexity |

| √ | Most widely known and used route | √ | Procurement is fully open book |

| X | Possible cost escalation ahead of agreement of contract sum | X | Price certainty not achieved until the last package is let |

| X | Can lead to adversarial PCSA and post-contract relationships | X | Needs an appropriately experienced and hands-on client, construction manager and commercial team (a long-term commitment) |

| X | Takes time and care to properly complete design before tendering | X | Construction manager is not responsible for cost or time |

| X | Longer overall programme unless works on site overlap procurement, which can add to commercial pressures | X | Strict time and information control is required |

| X | Main contractor can act as a barrier between client/design team and trades commercially, creating less transparency | X | Risk of scope gaps only being found as later packages are procured |

08 / Newer procurement routes: insurance backed Alliancing

The approach of Project Partnering Contract 2000 (PPC 2000) has been developed with the relatively new insurance-backed alliancing framework (IBA), a novel form of procurement backed by a unique integrated project insurance (IPI). It seeks a one-team approach by setting up an entity for the project that includes all key project members in a single special-purpose vehicle (SPV), all of whom have a contractual obligation and incentive to achieve success against agreed KPIs.

It has been used in practice, most notably for the Institute of Transformational Technologies (IoTT) for Dudley College, completed in 2021, which was delivered one month early and £613,000 below the bespoke IoTT benchmark. The building has a running cost estimated at some 62% below the last pre-IPI building procured by the college, which used a traditional design and build contract. The Cabinet Office was sufficiently impressed to state: “The potential this [IPI] has for changing ‘normal’ commercial behaviours towards creating a truly integrated team can’t be emphasised enough. It is radically different, but then we’re looking for radical improvements to project delivery.”

IBA is different from other procurement routes because:

- The alliance is formed of the client and equal partners, including consultants and the supply chain, which are appointed against a strategic brief that defines the need (not the solution) and the investment target.

- The partners are selected for their experience, technical capabilities and, crucially, behaviours of the people proposed for the project, without traditional sub-economic and illusory pricing.

- Under the innovative contract the alliance acts as a virtual company, sharing collective responsibility (on a no-blame/no-liability basis) to achieve best-for-project outcomes that meet the client’s needs.

- Following cultural and commercial alignment, the alliance members – supported by influential (named) suppliers – collaborate to devise the best solution within the investment target, which is confirmed as such by independent technical and financial risk assurers.

- A focus on which opportunities and risks should be allowed for in the target cost and how the alliance members’ gain/pain incentive will be allocated ensures the process is not without competitive tension. Independent facilitation is provided to nurture the collaboration throughout and to confirm its robustness.

- The insurers will only accept the IPI policy if these assurances are given. The partners have the comfort of knowing their limits of liability because the pain-share becomes the fixed excess on the cost overrun policy.

- The IPI policy covers the client, partners and all suppliers for construction project all-risks and third-party liability as well as cost overrun and 12 years’ latent defects, all with rights of subrogation waived. IPI replaces professional indemnity insurance, which is blame-based.

- The alliance board and its integrated project team (IPT) work top-down from the agreed target cost to deliver an outcome fit for the purpose defined in the strategic brief. Only significant changes to the brief or force majeure type events entitle review of the cost and/or time targets.

- Payments are made through a trust account directly to the partners and named suppliers against forecasts and reconciled in the next month, with no retentions, bonds or warranties applied.

- Completion means completion. Following the all-clear by the technical assurer, the latent defects element of the IPI policy comes into effect for 12 years. The partners continue to provide soft landings support for a minimum of 12 months.

IPI has not found greater and faster traction on major London schemes, probably because sponsors would need to be comfortable that its collaborative, skin-in-the-game approach – with early contractual commitments to an alignment of design and budgets based on benchmarks – can cope with the complexity and unique features of these projects.

09 / Newer procurement routes: project management consultancy

Evolving market demands and project complexity are prompting a re-evaluation of traditional delivery models, leading to the development of innovative approaches that offer alternatives to single general contractor models. These models often emphasise hands-on management, innovative procurement and supply chain integration, enhancing value for complex projects.

Project management consultancy (PMC), which has long been used in the oil and gas sector, is now being developed as a strategic model for integrating delivery and providing client control. This approach can lower costs by reducing risk layers, although some risks are passed to the client.

PMC offers an independent consultancy service throughout the project lifecycle, from strategic consultancy to commissioning management. It integrates gaps between strategy, setup and delivery, with the project management consultant managing all design and construction activities as one cohesive team.

This model affords more time for better design and logistics planning but depends on the team’s behaviours and the involvement of a highly competent and specialised supply chain. Its application varies by market maturity and client needs; in London, it is not yet viewed as a principal contractor model, though it manages all stakeholders, not just trade contractors.

Turner & Townsend is exploring the PMC model’s application beyond its traditional sectors, and to gain momentum in the London commercial market it must address sponsors’ and tenants’ needs for a financial wrap and single set of material, design and workmanship warranties. Early indications suggest there is an appetite for the independent, start-to-finish, controls-led model that it represents.

10 / Conclusions

The UK construction industry has faced challenges over the past five years, affecting its ability to deliver major projects effectively, efficiently and with commercial success. The fundamentals of a successful commercial project remain, and we should focus on getting them right to boost confidence among clients and contractors. All parties suffer when a project fails, yet the industry has shown impressive adaptability and resilience in response to recent shocks. This raises the question of why such behaviours are not applied consistently to prevent frequent project failures.

The UK construction industry has skilled professionals and effective systems, capable of creating high-quality, low carbon buildings using data and digital technologies. However, past initiatives for widespread improvements have not universally succeeded. Procurement systems are established and provide a solid framework, but consistent success remains elusive.

The answers surely lie in how projects are set up, with clear goals, effective leadership and appropriate teams, ensuring the procurement system aligns with the client, market and project specifics. This is the foundation of trust and collaboration, which are the behaviours vital for success.

Acknowledgments

Steve Watts would like to thank Turner & Townsend colleagues Mark Lacey, Mike O’Donnell, Andrew MacGregor, Rachel Coleman and Kishan Patel, as well as Martin Davis of IPI Initiatives, for their valuable contributions to this piece.

2 Readers' comments