As the growth potential of countries becomes increasingly reliant on key cities, EC Harris looks at how Doha is driving Qatar’s vision of economic diversity

01 / Introduction

World cities will increasingly become the focus for major programmes delivering economic and social infrastructure. Planning and managing large-scale developments to meet growing demand, and mitigating risks and negative consequences of development are all part of creating global, functioning cities - cities that collaborate and compete independently of their host country. Doha is such a city. Home to 47% of Qatar’s 2.2 million population, it is the economic, cultural, commercial and educational hub of the country, accounting for a significant proportion of its GDP. In the wealthiest country in the world, where GDP is predicted to double in the next decade, Doha’s position as a world city will progress apace.

Sitting on the Arabian Gulf the city already acts as a gateway to the Middle East, providing a location for inter-regional meetings, including the recent Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) summit where inter-gulf harmonisation was high on the agenda. Its economic growth, fuelled by high population growth and urban living (98% live in urban areas) brings both immediate and longer-term challenges to the city. Integrated transport systems and public transport connectivity will be an essential element of success, as is investment in housing, health and utilities. Levels of capital expenditure in the city is rising and was £9bn in 2013/14. Add to this the challenges around hosting the 2022 FIFA World Cup and Qatar’s Vision 2030 focusing on economic diversification: Doha’s success as a major city will be critical.

In a country where nationals represent just 23% of the population, expats the remainder, and where men outnumber women three to one, Doha’s development has to embrace the country’s immediate needs for homes, access to education and transport infrastructure while looking at how it can be a sustainable, modern, knowledge-based economy into the future, less reliant on returns from the fluctuating hydrocarbon market.

02 / Economic and political overview

Doha is the epicentre of government in Qatar. There are no political parties and no elections. The emir, 34-year-old Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani, is head of state and head of government. He is supported by an appointed advisory council that has no legislative powers but can advise on policy issues. The government funds free education, healthcare, water and electricity alongside providing job guarantees for its citizens and grants for housing. This contributed to socio-economic stability during the Arab Spring; however, Qatar’s relationships with other countries have sometimes been tense. At a regional level, Egypt has questioned its involvement with the Muslim Brotherhood, and it has faced international scrutiny over migrant labour.

While falling global oil and gas prices have slowed Qatar’s predicted annual GDP growth to 6.5%, its sovereign wealth fund stands at around £73.3bn. The government has the capacity to continue to bankroll Qatar’s economic growth, but is actively seeking increasing private sector involvement in delivery. For example, since 2010, tax incentives have been offered to non-domestic firms to encourage foreign investment. Corporation tax was reduced from a maximum of 35% to a flat rate of 10%, and tax-free zones have been set up.

03 / Construction sector

Doha’s construction industry is experiencing a period of frenzied activity with the largest projects primarily in the transport and real estate sectors. Construction was one of the largest contributors to non-hydrocarbon GDP growth in 2013 at 2.7%, and the value of work done for large projects in 2012/2013 was over £9bn.

Due to a rapid increase in the volume of workload in Doha and the wider GCC regions, there is a risk of a repeat of the high levels of construction inflation seen in previous development cycles. EC Harris has previously forecast that at peak levels of activity, and without appropriate mitigating actions, there is a risk that inflation over the period 2016 to 2019 could reach 18% per annum. With growth rates in the developing world stalling and falling commodity prices, some of this pressure will ease. However, with large programmes such as those currently being delivered in Doha there is a risk of delay in the procurement of construction work, related to both client and supplier capacity. The impact of these delays is not only a growing backlog of work and an increased risk of higher levels of peak inflation, but also a lack of contractor readiness when work finally accelerates.

04 / Infrastructure

Qatar will spend around £130.7bn on infrastructure projects in the lead up to the World Cup. In 2014 alone, £4.5bn worth of construction contracts were signed by Ashghal, the State Public Works Authority, which oversees roads, drainage, sewerage and buildings construction. Ashghal, along with Qatar Rail, oversees all infrastructure developments. One key programme is the Inner Doha Re-sewerage Implementation Strategy. At roughly half the cost of London’s Thames Tideway project, this £1.73bn scheme will provide drainage infrastructure for the southern part of Doha. It includes more than 40km of deep tunnel trunk sewer and more than 70km of lateral interceptor sewers as well as advanced sewage treatment works. The project aims to meet the needs of Doha’s population for 50 years. Construction is underway, with completion due in 2019.

05 / Rail

Approximately £15.3bn is being invested in metro and rail network programmes as part of the GCC rail network plans. It will consist of 216km of railway lines and 38 stations; it should be operational by 2020, with a final completion date of 2026. Questions have been raised by industry commentators (like the Qatar business magazine, The Edge) on its feasibility given Qatar’s hot climate and the congested nature of Doha itself, which will make construction in the city difficult. Meanwhile Qatari’s love of their cars (the country has the highest number of cars per capita in the world), throws into question the ultimate utilisation of the railway network.

Qatar Rail recently awarded four contracts of approximately £5.2bn for phase 1 of the Doha Metro. With delivery anticipated in 2019, it includesfour rail lines and an underground section in Doha centre. It will link stadiums for the 2022 World Cup. Timely completion will depend on effective communication between multiple contractors, and a sufficient supply of imported building materials, for which the Metro is competing with several other in-country mega projects. Competition between the Metro and other major programmes may lead to high levels of cost escalation.

06 / Roads

Qatar’s road system radiates from Doha. The government is keen to facilitate easy movement within the capital and the country. Ashghal’s Expressway Programme aims to improve Qatar’s road system on a national scale. Investment between 2010 and 2017 is estimated at £2.8bn, and should deliver 900km of road with overall investment levels likely to be significantly higher across a number of key projects.

A major Ashghal transport investment in Doha itself is the Sharq Crossing Programme, which consists of three bridges linked by an immersed tube tunnel. The 12km crossing will span Doha Bay to connect the new Hamad International Airport, Katara Cultural Village and the West Bay financial district. Construction will start in 2015 till 2021. The project’s budget is around £7.7bn. EC Harris is working with Fluor to provide programme management and construction supervision services.

07 / Ports

The Port of Doha is Qatar’s largest port but, in efforts to improve the city’s strategic importance, a new port is being constructed in south Doha. Doha’s new port will cost £4.7bn, with the first phase due to complete in 2016. When completed the 26.5km2 development will be the largest greenfield port development in the world and, in addition to strengthening Doha’s role as an international trading hub, will be critical in supporting the delivery of other projects in Doha by increasing its capacity to manage the flow of imported construction materials.

08 / Airports

Phase 1 of Doha’s Hamad International Airport opened in April 2014. This delayed and over-budget development (estimated at £4.8bn: final cost over £9.6bn) replaces Doha International Airport. The airport can handle around 30 million passengers per year, rising to almost 50 million when phase 2 is complete post 2015. Subsequently this will be further expanded to cater for 90 million passengers. The scale of development is a sign of the confidence in Doha of its ability to become a cultural centre, and to attract increasing numbers of regional and international tourists. Developments like this also increase Doha’s importance as a regional transport hub in direct competition with Dubai and Abu Dhabi.

09 / Water

Due to its geographical location and geological formation, there is a scarcity of reliable surface and fresh water in Doha, as in the rest of region. Annually Doha has the same amount of rainfall as London has in November alone. Surrounded by subtropical desert, Doha relies on desalination of sea water to supply water to its residents, who consume twice as much water on average as Europeans.

A £14bn water and power infrastructure investment is expected up to 2020. With demand for water expected to increase by 50% during 2022, the imperative to invest is evident. Emergency water supplies are secured by five security mega-reservoirs, one of which is in south Doha. Water supply is overseen by the government-owned Kahramaa (although individual plants are privatised) and the Qatar Water and Electricity Company. In Doha, Kahramaa is undertaking a large-scale extension of the water distribution network, which includes extending the current network by approximately 165km of pipes and fittings. It is in its fifth phase, with completion due 2015.

10 / Commercial and leisure

Developing football stadiums (newbuild and renovation) in time for the World Cup is estimated to cost £1.9bn. Simultaneously, as much as £10.8bn will be spent on doubling the number of hotel rooms. The 1,000-room Silver Pearl Hotel for example, built on a man-made island a mile from Doha’s coast, is estimated to cost £1bn and will include restaurants and high-end retailers. Yet while the Silver Pearl is targeted to complete in time for the World Cup, investment in the commercial sector is also creating change in Doha in advance of that event. For example Doha Festival City is a £288.8m joint venture between the Gulf Contracting Company and ALEC Qatar, and will be the largest mall and entertainment complex in Doha.

11 / Social and cultural

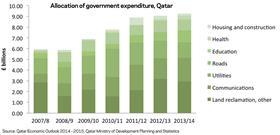

In addition to infrastructure, £4.6bn is earmarked for education in 2014/15 along with £2.7bn for health, an increase of 7% and 13% respectively. Private sector engagement is evident in Doha, with several American universities operating in the city, recently joined by University College London.

Alongside education and health sits cultural infrastructure, such as museums and parks. New museums, including the Arab Museum of Modern Art have been springing up in recent years in and around Doha. More are planned. For example, a national museum is due to open in 2016, at a construction cost of £276.7m. Existing facilities are also undergoing major works. For example, Doha Zoo is being transformed into a safari park, with the first tranche of contracts (valued at £20.4m) awarded in March 2014.

12 / Residential and mixed use

Residential construction in Qatar grew by 13.2% in 2013, and will continue apace to meet growing housing needs. House prices are rising, for example properties in The Pearl (one of Doha’s exclusive developments) rose by £20,000 in one month alone from £663,000 to £682,000 - a year-on-year rate of more than 30%. Rent prices are also on the rise, increasing by 16% year-on-year, adding to housing shortage pressures in the city. With no enforced rent cap, landlords are free to set their own contracts.

There are numerous residential developments in Doha. The mixed-use Msheireb Downtown Doha development in the heart of old town: “the world’s first sustainable downtown regeneration project”, costs £3.5bn and will complete 2016. Domestic and international contractors are to deliver this project; phase 1 involves a joint venture between Carillion and QBC.

There is also concerted effort to develop residential schemes outside Doha in an effort to relieve city pressures. The development of Lusail City, 22km north of Doha is one of the largest commercial projects in the Middle East. When completed in 2019 it will be home to 200,000 residents and a thriving mixed-use economy.

13 / Outlook

Doha’s public programme of roads, expressways and metro, accompanied with private construction activity in commercial and residential real estate will continue apace, with the medium-term goal of hosting the 2022 World Cup in a dynamic capital. Planning and building resiliency into design that ultimately improves urban sustainability and connects people and cities intelligently will see Doha’s stock as a global city rise. Qatar recognises risks around the scale and complexity of the infrastructure project portfolios, and that avoiding construction inflation surprises requires effective programme management across sector construction programmes, incorporating co-ordinated procurement strategies, a clear overview of the impact of delay and partnership working.

Key data:

Sources used in gathering data for the article include: Ashghal, Building Magazine, Business Monitor International, CIA World Factbook, Construction Week, Doha News, The Economist Intelligence Unit, The Heritage Foundation, IHS Global Insight, International Monetary Fund, NAI-Qatar Real Estate, Qatar Foundation, Qatar National Bank, Qatar Statistical Authority, Trading Economics, World Bank.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Nick Smith and Neil Sethi of EC Harris and Julie Nguyen of ARCADIS, for insight into Doha

2 Readers' comments