The 140mph High Speed One service to St Pancras could be the future of rail travel if commuters are prepared to pay

The 07.45 service from St Pancras to Ashford International made a prompt start from Platform 13 this morning as the UK’s first domestic high speed train headed out of the restored Victorian station over the £5.2bn line.

When operational on December 14th, the new 140mph service will slash journey times to Ashford from an hour to 37 minutes. Ebbsfleet will be a mere 17 minutes away.

On this first voyage, transport and technical journalists jostled with broadcasters manoeuvring cameras and sound equipment down narrow commuter carriages. They mingled with senior Southeastern and Network Rail management and two transport ministers aboard the one million pound-per-carriage Hitachi train.

After departing from north London, the train immediately entered a 12-mile tunnel before re-emerging at 07.56 into the unprepossessing landscape of Rainham Marshes, all ship containers and industrial wasteland.

Two minutes later we were at the Dartford Crossing, watching a nose-to-tailer on the QE2 Bridge. Southeastern Commercial director, Vince Lucas said these were the people he was trying to target. Large billboards will soon be unveiled by the M25displaying HS1’s benefits.

Ebbsfleet whizzed by in a flash just before we went over the Medway at 08.03. The railwayman has a new vision for the mothballed £3bn Land Secs Ebbsfleet Valley site: where once it was to be the site of 10,000 home sustainable megatown now it is to be: “The largest park and ride in the UK, possibly in Europe,” with space for 9,000 cars, 5,000 places already having been built. He hopes to attract new passengers from within the so-called ‘Ebbsfleet Box” which includes Otford, West Malling, Maidstone and Gillingham.

Through the rolling Kent countryside we shot at 140mph, debating whether the commuters would be prepared to pay £8 a day more for an extra hour on top of their £113 weekly season ticket. Kings Cross may be a growing business district, but most people will want to arrive in the City or the West End.

One Kent journalist said he would cough up the money if it made his wife happier. “She thinks I’ll just spend the extra time at work, though” he added.

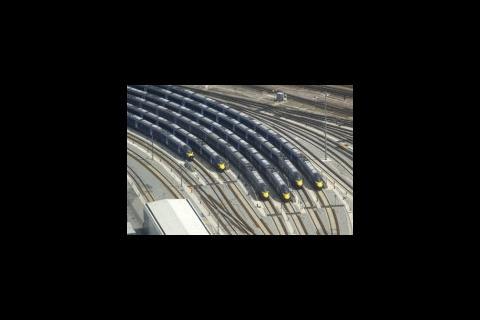

Having bought over 20 trains from the Japanese maker and with the government hoping to open up the service to other international operators, there’s a lot at stake for the operator. There’s nothing special about the trains themselves; standard issue powder blue and grey commuter trains. I didn’t feel like I was on a bullet train, despite the vehicle’s pointy nose.

We arrived promptly in Ashford at 08.17, which still looked a lot like Ashford. We shuffled around a bit on the platform, but there wasn’t enough time to go to TK Maxx. We were asked to get on board, then reversed direction and headed back to London, the hacks being forced to move into the front six carriages to ensure we had “spokespeople” to hand.

On the return trip, rail minister, Lord Adonis said – not for the first time – that HS1 marked the beginning of a new high speed era in British train travel. He has set up the optimistically-named High Speed 2 company to examine speedy lines from Heathrow to the West Midlands and beyond. But is this likely given the state of the UK’s finances?

Ever-sceptical transport commentator, Christian Wolmar and Rail editor, Nigel Harris debated the issue. Wolmar thinks the country is too small, existing services too reliable and high speed rail to pricey to make it off the drawing board, at least in the next couple of decades.

Harris, more optimistic, said that the UK had a unique chance to build on the first generation of European high-speed services such as the TGV, which made mistakes we can learn from, including letting political will dictate too many stations on the line and forgetting to include upgrade capacity on the track.

We were back in London before 09.30 without much of a hitch although the air conditioning was somewhat bracing. The smooth sailing was to some peoples’ disappointment. “I only came along in the hope that it would break down,” said one consumer hack.

But for once, British technology and service came through.

1 Readers' comment