HOW THEY MADE IT - Despite that minor mishap, Chris Wise is proud of the 20 years’ work he did at Arup. He tells Dan Stewart what he learned – and why the best is yet to come

How did you get your first job at Arup?

I was interviewed by a guy called Tom Henry. We were walking around Southampton campus and he pointed at a building and asked, “What do you think?” I said, “I think it’s rubbish”. And he replied, “Well, I designed that.” He took it in great humour and he clearly appreciated my honesty because I got the job.

Before he hired me, I knew nothing about Arup except that they’d done Sydney Opera House. I didn’t realise how lucky I was to get a job there until I’d worked for them for five years.

You stayed at Arup for 20 years. Was that too long?

Because Arup is a multinational and multidisciplinary company you can work in lots of places and areas, so I didn’t have any great temptation to move around.

Also, Arup has always had a liberal attitude to taking time off. They encourage people to go abroad, whether it’s for work or just to go and see things. I took a year’s sabbatical to travel and they kept a job open.

How did the year off change your career?

Going travelling for that year was far more important than university. It helped me work out what I actually wanted to do. It was the moment I began to feel that the subdivision of engineering into all sorts of different disciplines was nonsense, frankly. You look at the Taj Mahal and there were no structural engineers working on it. I realised you have to understand the architecture if you’re going to do the engineering and vice versa.

How did you develop your management style?

I learned a lot from working in Australia. I spent six months there working with John Nutt, who was on the Sydney Opera House. During meetings in England I’d never seen anyone swear, but there everyone used to swear at everybody and call a spade a spade. It appeared to be a much better way of communication because people were actually exchanging information rather than going through the motions. It was a “fucking hell, it’s a flaming disaster, we’ve got to come back tomorrow and get it fixed” approach.

You became a director at Arup at the age of 35. Was there resentment at your quick rise?

I was bounced up the ladder very quickly. I think that’s because I’m thought of as an unusual engineer, so I wasn’t seen as competition. All the other directors could afford to be magnanimous if they had a strange leftfield character hanging around because I wasn’t going to take over the world, or do what they were doing.

Was there a lot of pressure on you?

The years between 1992 and 1995 were very pressurised. I’d been made a director, I was running the Commerzbank project in Frankfurt and I was doing 35 or 40 projects for Foster + Partners simultaneously. I never found that part difficult. I’d just go round to Fosters and do them all at once. I’d take someone with me who was working on that project and they’d go back and sort it out. It was a very shorthand way of working.

The Commerzbank was much more pressurised, because I’d have to fly to Frankfurt once a week, which was a nightmare. We had a three-year-old son and it all became very difficult. But some of the best projects came out of that period.

What’s the biggest mistake you ever made?

The most obvious one was when I made the decision to take out the dampers on the Millennium Bridge. During the design process, we had a series of detailed technical meetings about how the bridge was going to perform. All the best people at Arup were there. So, in one of those meetings, we went through the whole scenario and it appeared obvious that we didn’t need dampers. So we said, we’ll take them out. Obviously, history has shown that perhaps we didn’t have all the information we needed ...

Do you get bored of talking about the wobbly bridge?

Not at all. I’m really proud of what we did on it. We took a risk, we put our skills to the test and, although we didn’t quite pass that test, we did pass in lots of other ways. I would take all the short-term rubbish that was associated with it in exchange for being responsible for linking the richest and one of the poorest boroughs in our capital. That’s a privilege that not many people get.

What was your favourite project?

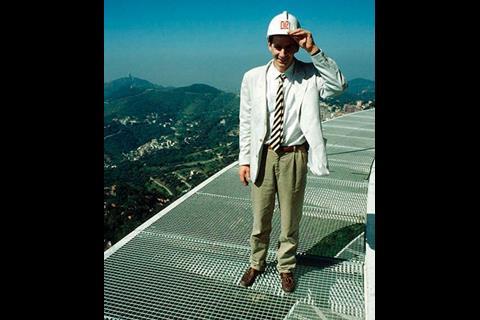

Barcelona Tower, because I was really young when we did it and it was such a buzz to see this thing rearing up on a mountain. It was huge fun. That was an important project because there was only one person on a board of 40 directors who wanted it to go ahead. We’d sit on one side of a table with all these directors puffing cigars on the other, and they’d say, “We don’t want it. It’s too expensive.” By the end of the project, though, we had converted them all. To convince people to change their perceptions of what’s possible through your actions is important. I love that tower; every time I see it I chuckle.

And your biggest regret?

The one that got away was our walking building for the British Antarctic Survey. It was a magnificent, ground-breaking project – a fuel-cell-driven building that was wind and hydrogen-powered. It was like doing a space station on earth. But it was £2m over budget and we couldn’t get the Treasury to release the extra money. If anyone else wants a walking building, they should get in touch.

What was your greatest achievement?

I think it’s yet to come. I’m only 50, so I’ve got loads of time and our practice has only been going for seven years. I hope Expedition Engineering will go on to shake up the profession. I’m hoping we can revolutionise the way the industry works.

Give us some advice

First, the skills you need for art or music are the same as you need for engineering. Because there are so few people who know that, if you bring those skills to your job you’re going to be very successful. Second, if you can balance a reasonable income with the fact that it’s a pleasure to get up every morning, then enjoy it. Not many people get that.

CV Chris Wise, 50

1956-1968

Brought up in Surrey and went to Holmesdale School, Reigate

1968-75

Went to Reigate Grammar School, where he did A levels in maths, physics and chemistry – and played in the first XV rugby team

1976-79

Civil engineering degree at Southampton University, during which time he worked on Salisbury Cathedral with Peter Taylor

1979

Joined Arup

1982

Took a year’s sabbatical to travel around South-east Asia and India

1986

Established Arup offices in San Francisco and Los Angeles

1991

Built Barcelona Tower

1992

Became youngest ever director of Arup

1992-95

Worked on Commerzbank headquarters in Frankfurt

1997

Worked on the air museum in Duxford, Cambridgeshire, which won the Stirling prize

1997-99

Worked on Millennium Bridge

1999

Founded Expedition Engineering with Sean Walsh

2002

Awarded honorary fellowship of the RIBA

Postscript

Search for current opportunities in engineering at www.building4jobs.co.uk

No comments yet