A QS has been sued for valuing work that was defective. Luckily for it, the law is clear on this point. But surely QSs have a duty to speak up if they spot something’s wrong?

T his story will come as a relief to all you quantity surveyors, or rather, those of you whose job it is to carry out monthly valuations under JCT-type contracts. On the other hand, if you’re a project manager working with the NEC, you might get twitchy. So what’s up?

Mr & Mrs Dhamija were disappointed with the design and construction of their house in Virginia Water, Surrey. There were, they alleged, defects. So a court action was started. In the firing line was a contractor called Sunningdale Joineries, then an architect called Lewandowski Willcox, then a QS, McBains Cooper Consulting.

The PQS has a limited duty when doing the monthly valuation, at least with regard to defective work. In real life, the architect expects the QS to poke their nose into the standard of work

The first claim against the QS was that they overvalued. The second claim was about defects. The Dhamijas said McBains owed them a duty “only to value work that had been properly executed by the contractor and was not obviously defective”. It is alleged there are hundreds of items that constitute individual breaches of contract by McBains.

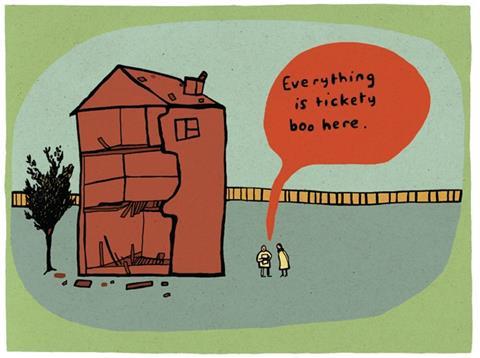

The line taken by the QS was that a quantity surveyor is not liable to the employer for defective works. But you can see what irks the customer, can’t you? After all, if a QS is experienced in construction, it will have a nose to sniff iffy work, and should not value it as if it were tickety-boo.

So what does the law say? Forty years ago a major construction dispute decided that an architect was negligent if its interim payment certificate failed to make proper allowance

for defective works carried out by the contractor. The architect had argued that its duties did not extend to telling QSs to exclude defective work from the valuations. The court would have none of that. An interim certificate was a mere approximation of the value of the work as it progressed, assessed by the QS without any detailed inspection of the works; the object was simply to provide a reasonable payment for the contractor based on a comparatively cursory examination of the site.

Seemingly, evidence was given in that trial that if the architect did not tell the QS about defects, the QS would not be expected to make allowance for them, and that was accepted. The QS was entitled to assume that the work had been done properly. But where the work was clearly wrong, then it had to be excluded. The court decided 40 years ago that the quality of work was always the responsibility of the architect and never the QS. The architect is duty bound to notify the QS in advance of any work that it, the architect, classifies as not properly executed, so as to give the QS the opportunity of excluding it.

In the Dhamijas case, Mr Justice Coulson also looked at the text books: Professional Negligence and Liability says the QS’ job is to independently assess the works carried out to arrive at a proper valuation. Jackson & Powell on Professional Liability, meanwhile, say the architect and QS must take care to ensure the claims for payment are reasonable and justified by the work done, in quality and amount, and they add that the architect should keep the QS continually informed of any improperly executed work.

Hudson’s Building & Engineering Contracts didn’t impress the judge. Hudson says that if the QS notices defective works while make its valuations, it should bring them to the architect’s attention in case the architect has missed it. Hudson adds: “Bearing in mind the high degree of skills professed by QSs … there would seem to be no reason why they should not also be joined as defendants by an owner, where, for example, the defects were so glaring that they should be seen by him in the course of valuation inspections.” But the Hudson view, said the judge, was not supported by any High Court case.

The court decided 40 years ago that the quality of work was always the responsibility of the architect and never the QS

The PQS has a limited duty when doing the monthly valuation, at least with regard to defective work. In real life, architects rely on the PQS’ eyes and ears; they expect them to poke their nose into the standard of work when carrying out a valuation. I rather suspect Hudson’s impressions are not that far off the mark. If I were a PQS I would be nudging the architect if I spotted doubtful work. The JCT says it is the architect that is in the frame for quality. The NEC says the project manager should look at the quality and value work done. Eyes peeled.

No comments yet