Social value is an element of project value that is weighted increasingly heavily when evaluating project bids. But what exactly does it comprise, how can it be effectively delivered – and more challengingly, how is it calculated? Alinea and Social Value Portal explore the issues and offer examples of social value in practice

01 / Introduction

Sustainability has always been framed in terms of the three tenets of social, economic, and environmental considerations – or people, profit and planet, to use its alliterative reference. In recent years the “people” aspect has firmly entered our collective conscience, and health and wellbeing have been pushed up project agendas through guidance such as the WELL Building Standard.

Economics will always be a fundamental element in any business transaction, but that bottom line is now influenced not only by a longer outlook, which accounts for operational costs, but also by an increasingly nuanced view of value.

Climate change is the area that will arguably continue to receive the most attention, as real estate looks to genuinely reduce its carbon footprint and adverse environmental impacts, with much more focus on whole-life low carbon design, backed by a plethora of guidance and corporations’ environmental social and governance (ESG) commitments.

This sharper focus is prompting a wider and deeper assessment of buildings, over a longer time frame – a view described well by the term “social value”. This shift encourages sustainable buildings (through low carbon materials, low energy installations, generous communal spaces, biophilia and passive design) and asks us to consider how we can make positive impacts beyond a project, in the spaces between buildings as well as those within them, and to society.

Such a range of parameters will inevitably include some values that appear subjective, but that should not prevent their quantification, because putting numbers to the metrics is the only way to determine their true value.

02 / Defining social value

Broadly defined by the Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012, which came into force in January 2013, social value requires all public bodies to look beyond the financial cost of a contract and consider how the services they commission might improve the economic, social and environmental wellbeing of an area.

For real estate, social value may be defined as “the wider social contribution that a development creates for society through how it is constructed and managed including the economic returns to the local economy, the wellbeing of individuals and communities as well as the benefits to help regenerate the environment”.

It transforms the relationship between the public and private sectors. The new construction playbook (see panel, right) as well as Procurement Policy Note 06/20 support social value as a central element to government buying, with a minimum weighting of 10% at procurement stage.

There are some overlaps with the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), which defines sustainability around three core dimensions (economic, social and environmental). Local authorities are embedding social value into the planning process, but weightings and importance vary across the country – with some councils, such as Manchester, applying a weighting to social value that goes as high as 30%.

The construction playbook

Who is it for? Public sector contracting authorities and the wider construction industry in general. Core aims include getting projects right from the start by:

- Aligning to UK 2050 net zero commitments to deliver greener facilities

- Investing in construction projects that drive maximum economic, social and environmental value

- Promoting social value to help local communities recover from covid-19, tackle economic inequality, promote equal opportunities and improve wellbeing.

Social value is mainly addressed in the evaluation and award section, which says that:

- Social value should be explicitly evaluated in all central government procurement where requirements are related and proportionate to the subject matter of the contract (10% minimum weighting).

- An evaluation model should be used, drawing on outcomes from the project scorecard, to assess social value in projects.

- All completed GMPP (government major projects portfolio) projects will be required to publish an initial close-out report and a later (after five to 10 years) evaluation of their long-term social benefits, based on the project scorecard.

03 / Measuring social value

There are a number of methods to measure and report on social value, but the most widely used is the National Social Value Measurement Framework, which is otherwise known as National TOMs (standing for themes, outcomes, measures).

The National TOMs were developed by the Social Value Portal and the National Social Value Task Force, and are endorsed by the Local Government Association. They are a free resource with a specific real estate plug-in designed to reflect sector-specific priorities and opportunities.

Using this framework allows organisations to calculate the total financial benefit from an activity or development in terms of fiscal savings to central or local government through social welfare payments, or economic benefits from additional local spending, as well as longer-term social wellbeing to individuals.

The National TOMs are structured around five core themes with 20 linked outcomes (see table opposite), and 40 measures with associated financial proxy values.

The principal benefits of using the National TOMs as the standard for reporting social value in real estate are that they:

- Provide a consistent and comparable approach to measuring and reporting that is robust and transparent

- Allow organisations to compare their own performance by sector and provide industry benchmarks to understand “what good looks like”

- Reduce the uncertainty surrounding social value measurement for businesses, allowing them to make informed decisions based on robust quantitative assessments and hence to embed social value into their corporate strategies

- Ensure that social value is maximised for communities and those people being affected by the new development

- Provide a basis for developers to describe their wider contribution to the local communities and for planners to make more informed decisions.

| Theme | Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Jobs: promoting local skills and employment | More local people in employment |

| More opportunities for local people | |

| Improved skills for local people | |

| Improved employability of young people | |

| Growth: supporting growth of responsible local businesses | More opportunities for local SMEs and VCSEs |

| Improved staff wellbeing and mental health | |

| Reduced inequalities | |

| Ethical procurement promoted | |

| Social value embedded in the supply chain | |

| Social: healthier, safer and more resilient communities | A healthier community promoted |

| Vulnerable people helped to live independently | |

| More working in the community | |

| Environment: decarbonising and safeguarding our world | Carbon emissions reduced |

| Air pollution reduced | |

| The natural environment safeguarded | |

| Sustainable procurement promoted | |

| Innovation: promoting social innovation | Other measures |

04 / How can real estate deliver social value?

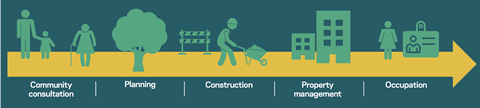

Social value is delivered across the whole lifecycle of a development, from design and construction, through to the building being in use, including property management and occupation.

Research by the British Council for Offices and Legal & General, in their publication Measuring Social Value in Offices, and work by the UK Green Building Council indicate that the potential contribution that a building can make to society is significantly higher where there is in place a comprehensive social value strategy covering every stage of its lifecycle. For a typical development, the social value delivered over 20 years could be up to four times the upfront construction costs.

The social value strategy is the golden thread to maximising benefits throughout a scheme’s lifecycle

- During design Design teams are ultimately responsible for developing the plans that unlock the potential for community activities and value creation. They can also add social value through their own corporate social responsibility activities, such as through creating local jobs and apprenticeships and by getting involved in community outreach programmes.

- Meanwhile uses Often led by the development team, so-called “meanwhile uses” can bring an empty site alive and create social value. This is especially the case for large sites with masterplans where work has yet to start on some parts.

- During construction Some social value conditions may captured within a section 106 agreement or condition, such as requirements for local labour, local spend and apprenticeships. Innovative contractors will do much more than this, including working with partners to provide job opportunities and training for those with poor access to the jobs market, increasing local supply chain spend, digital mentoring and embodied carbon reductions.

- In use: property management The workplace and facilities management team have a role to play in delivering social value through how they procure facilities management services, such as security staff, maintenance and repairs, and cleaning. They also are vital in bridging the gap between occupiers, the community and the local council to unlock opportunities for occupiers to employ local people, reach local schools and volunteer in the community.

- In use: occupation The occupier has the potential to create the most social value through how it engages with the local community, provides jobs and training opportunities for local people, engages with the local supply chain and strives to protect the environment.

Typical distribution of social value throughout the lifetime of an office building

Meanwhile uses

- Community activities

- Events and cultural activities

Construction

- Local labour and spending

- Support for SMEs

- Expert business advice

- Volunteering

Workplace management

- Local security workforce

- Local suppliers

- Free community spaces

Occupation

- Local labour

- Apprenticeship scheme

- Work placement

- Community project support

05 / Designing for social value

Social value can be delivered by the project team through two principal pathways, which can be characterised as the “how” and the “why” of the scheme:

- How the design is delivered – the corporate social responsibility activities in which the design team get involved during the project, including how the community is engaged and given agency.

- What is designed and how the spaces created allow others, including the property management team and the wider community, to create social value.

The old ways of discharging responsibilities for delivering social value through stakeholder consultation (and ultimately through the design) – as well as through section 106 commitments – are no longer enough.

The delivery of social value is the responsibility of the whole project delivery team, including developers, designers, project managers, contractors and their supply chain, other consultants and the workplace and facilities management team.

Questions for the design team to consider should include:

- Does the design respond to local need, and does it have the potential to unlock opportunity?

- How does the design make the most of opportunities to use local employment?

- How can the building be designed to maximise the opportunities for use so that local businesses can become involved in its delivery?

- Can the design team specify local materials for construction?

- How will the spaces be used in the “meanwhile” period, running up to works commencing, and after completion to ensure opportunities are maximised?

- Can the design team go beyond the finishing line by developing an events calendar for the first 24 months of use?

- Can the development and design team also contribute to creating more social value, and if so, how?

Using a project charter

Lynn Summerfield of British Land on the developer’s AHMM-designed office and retail scheme to refurbish, extend and add new buildings at Blossom Street in London’s Spitalfields:

At Blossom Street we have introduced a project charter for the delivery team. The charter’s stated aim is to “make a difference to the lives of people in the project team, in the local community and those we interfaced with”.

Established, managed and owned by a working group of cross-disciplinary project team members, the charter is a non-contractual requirement setting a series of objectives for the project delivery phase covering: community, mental health, environmental awareness, diversity and inclusion, project awards, charity, team-building and wellbeing.

Alongside the charter we have a community engagement strategy to ensure all project team members understand the importance of our local community and are empathetic to those living next to our developing site.

This engagement strategy was put in place before the works began and sets out a clear plan for how we should engage and listen to our neighbours and the importance of being open, honest and personable in our approach through one-to-one meetings, opening our site up to the community and through more formal monthly update meetings.

06 / What is ‘good value’ in social value?

The Social Value Portal and procurement body Scape recently issued the first published benchmarking report for social value. It evaluates the social value data reported outcomes from a sample of more than 1,400 construction projects completed within the past seven years, ranging in contract size from £10,000 to over £1.4bn.

The table summarises the frequency of usage of the key measures, rather than money spent. Local employment and local supply chain spend are at the top of the list; apprenticeships and training come next. Together, these four measure types account for over 50% of the measures used.

| Local peopled employed | 16.09% |

| Local spend | 14.63% |

| Apprenticeships | 12.01% |

| Training opportunities | 11.19% |

| Car miles saved | 7.45% |

| Staff wellbeing | 7.25% |

| Employment of local people (working days) | 6.36% |

| Employment of people who are NEET | 6.19% |

| Donations to local community projects | 6.06% |

| Volunteering for local community projects (hours) | 5.44% |

The data also shows that it is not necessarily the bigger projects that deliver the most social and local value, with the smaller contract sizes (bands A to D) generating more social value in percentage terms than the larger projects. Band A projects typically delivered social, local and environmental value amounting to 25.9% of total contract value, Band D projects 24.3%, while band E and H projects delivered 14.2% and 13.4% respectively.

Some of the report’s key findings and recommendations are as follows:

- The average additional value delivered in the portfolio was around 25% of total contract value.

- Most of the added value being reported at the moment is specifically local value.

- Contract size does not determine the amount of social value added.

- Local spend as a percentage of contract value varies significantly across the country.

- While immediate “value” is predominantly unlocked through the local spend element, social or community value should be regarded as investment in a sustainable future.

- We need to move beyond standard GVA multipliers to understand need and build the evidence base for supply chain spend.

- Construction spend does not align strongly with areas of multiple deprivation (where arguably the economic impact of construction is most needed).

- We need to encourage the take-up of social value measures beyond those relating to jobs and skills, looking at alternative and complementary ways of measuring local economic value.

The data shows that social value is still a little way off being business as usual in public procurement, but we seem close to a tipping point, particularly with the advent of the central government approach via Procurement Policy Note 06/20 and the social value model.

However, when looking at retrospective projects, we should be mindful that social value is a rapidly evolving concept, and therefore we expect current and future projects to continue to push what “good” looks like and to extend their influence beyond the immediate area.

Case study: 245 Hammersmith Road

Sheppard Robson’s 245 Hammersmith Road is a 330,000ft2 commercial office completed in 2019 in the centre of the London borough of Hammersmith and Fulham. During construction, between 2017 and 2019, main contractor Lendlease achieved 211% against its social value targets set at the start of the project, measured against the National TOMs framework.

The total social value delivered as a percentage of the overall contract value, 28.2%, was well above the baseline target. Highlights from the project included a partnership with a local enterprise studio, volunteering at the local community centre, and supporting unemployed and socially disadvantaged people from under-represented groups in achieving industry recognised qualifications and with site experience through apprenticeships.

The development demonstrates how social value can be unlocked not only during the construction phase, but in how the property is managed. BNP Paribas Real Estate was appointed through a competitive tendering process that included a 10% weighting on social value. In turn it has embedded social value into its own supply chain appointments, ensuring each supplier has a target and maximises social value.

Working together with the Social Value Portal, the BNP Paribas team unlocked almost £650,000 worth of additional social value representing around 30% of the annual contract value. Key benefits included 40% local labour and four new opportunities for young people struggling to find work.

Project highlights

- 51.4% local employment, with £4.7m total value in employing local people (153 people employed)

- £42,500 value in apprenticeships and work placements, including over 700 weeks of training

- £26.1m local economic value, including £21.4m local supply chain spend

- £2.4m environmental value, with 148 tonnes of carbon savings and 26,654 tonnes of waste diverted from landfill.

02 / The future: helping our communities recover and renew

The concept of social value brings together all the facets of sustainability, with a particular focus on value creation for the local community. Covid-19 has focused the spotlight on this idea, strengthening the view that social value is here to stay as a measure of success for any endeavour.

Real estate will be at the forefront of society’s efforts to recover and renew, improving social mobility, boosting local economies, creating jobs, improving skills, and helping to level up the country.

It is only a matter of time before it spreads from the public to the private sector, meaning that we will no longer think about social, environmental and economic sustainability in respective isolation, but view and assess them together, to show that all buildings can be sustainable in the truest sense.

The size of the prize is huge: with an annual spend of £110bn in the construction sector and an average social value delivered of 25%, this could lead to additional value for our communities of over £27bn a year. Surely a prize worth fighting for?

> Also read: Collaboration is the key to social value

Acknowledgments

Contributors to this article include: Guy Battle and Nathan Goode from Social Value Portal; and Sam Gartell, Steve Watts and Rachel Coleman from Alinea Consulting

No comments yet