A deadly boiler explosion, half-built tunnels flooded by sewage and an “interminable tangle of timber”: here’s how we reported on the first part of the London Tube network

This week’s archive offering is a news item on the construction of the Metropolitan Railway, the first part of the London Tube network to be built and the world’s first underground railway line. Work had started in March 1860 following years of delays and would complete two years later at a cost of £1.3m.

Construction was beset by difficulties as the three pieces below outline. The first, written six months into the project, is an update on the works and an explainer on the complexity of the vaulting in the tunnels where they intersect. It also contains an account by an engineer of the “interminable tangle of timber” which has been built up underground.

The second piece is a letter from an engineer about the result of an inquiry into a fatal explosion on the site later that autumn. Two people were killed and another injured when a ”notoriously old and indisputably defective” boiler blew up. Disaster struck again in 1862 when the nearby River Fleet sewer burst and flooded the railway’s half-built tunnels.

Thankfully the line was a huge success when it opened in 1863, leading to two extensions later that year and a proliferation of underground lines in the decades that followed.

News item in The Builder, 22 September 1860

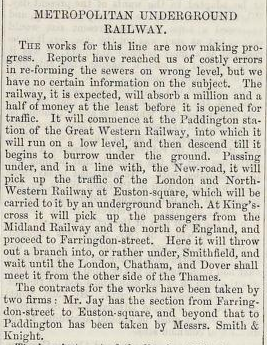

The Metropolitan Underground Railway

The works for this line are now making progress. Reports have reached us of costly errors in reforming the sewers on [the] wrong level, but we have no certain information on the subject. The railway, it is expected, will absorb a million and a half of money at the least before it is opened for traffic.

It will commence at the Paddington station of the Great Western Railway, into which it will run on a low level, and then descend till it begins to burrow under the ground. Passing under, and in a line with, the New-road, it will pick up the traffic of the London and North Western Railway at Euston square, which will be carried to it by an underground branch.

At King’s cross it will pick up the passengers from the Midland Railway and the north of England, and proceed to Farringdon-street. Here it will throw out a branch into, or rather under, Smithfield, and wait until the London, Chatham and Dover shall meet it from the other side of the Thames.

The contracts for the works have been taken by two firms: Mr Jay has the section from Farringdon-street to Euston-square, and beyond that to Paddington has been taken by Messrs Smith & Knight.

The heaviest part of the line is at King’s-cross. Straightforward tunnelling, or even going round a corner at a sharp curve, with nothing, to all outward appearance, to guide you as to the spot at which you may come out, is simple and easy to those who understand the business; but such a complication as that at King’s-cross seems thoroughly bewildering.

At King’s-cross there are two branch lines running up to the station, one on the east, the other on the west side. The two lines run in on a curve, the one from the west running in an easterly, the other from the east in a westerly direction, and they therefore cross each other something in the form of a letter X.

At the point of intersection the arch of the tunnel has in consequence to be groined. As the main tunnel is 28ft 6in in width, and the branch lines about 14ft, the necessity presents itself to combine in one arch at the point of junction two arches of a different radius.

The engineer, in a recent account of the works, says, “The tunnelling has to be carried out in forms which may be represented by a monogram formed of the letter X and two Ys, each leg of the letter X forming the upper limbs of the Ys, and all the arching and building up has to be made to fit accurately together. An ant’s nest, a rabbit warren, a colony of beavers, or a mole’s burrow would not be more intricate.

We fancy that we have explored the whole region, and traversed the whole maze, when we come upon the flicker of candles through an interminable tangle of timber, and are informed that the work there is the pointsman’s house, with retiring rooms. The immense baulks of timber supports become more and more numerous, and we feel something of a nervousness when we are told that this was and is the most critical part of the business.

The walls and arches of the small and large tunnels of the great bell-mouth press with such immense force on this pointsman’s dwelling, which is at the centre of the complicated junction, that it has been necessary to use the greatest possible precautions to prevent the whole from coming to one grand collapse. There are timbers upright, horizontal, diagonal, straight, curved, interlaced, and crossing and recrossing each other, till it becomes a marvel how it was possible to have got such masses under the earth and into any useful position.

The ground plan has now grown more complicated: the monogram of the two Ys and the X has received the addition of one large and two small Os, and these letters are placed in the forks of the two horizontally placed Ys. The “round house”, which is a sort of key of the position, is completely covered in by a circular dome, and here will be stationed the switchmen and signalmen, who will attend to the points necessary for running the branch traffic on to the main line: for the through trains – that is, from Paddington to the City – there will be no points to attend to at the junction, as the switches will, of course, be open.

The brickwork of the tunnel is 2ft 3in in thickness, and some idea of the extent of the work may be judged from the fact that 10,000 bricks are swallowed up for each yard formed as the tunnel advances.

Letter about the boiler explosion at King’s Cross, 1 December 1860, written by an engineer

Sir, the public have now before them the result of the adjourned investigation respecting the fatal explosion which took place on the Metropolitan Railway at King’s cross about four weeks ago.

In the first stage of the inquiry, immediately after the occurrence, the coroner very properly declared that it would be more satisfactory to himself and the jury if, before recording their verdict, they were to hear the opinions entertained by practical engineers who, after examining the remains of the engine, would be better qualified by their previous experience to throw light on the questio verata as to the cause of the accident, than they, the jury, by their proceeding with the inquiry, with the insufficient means at their disposal, would possibly be enabled to do.

The justice of this determination was too evident to be controverted. Yet, whether a verdict might not have been delivered on the first occasion, if the report of Captain Tyler, the government engineer, may be considered as anything but waste paper, is by no means clear. By what process of reasoning the jury reconciles with their verdict the evidence given by Captain Tyler is best known to themselves.

A locomotive engine, notoriously old, and indisputably defective in construction, explodes, killing on the spot two men, and seriously injuring another. The government engineer, among others, is requested to report on the cause or causes of the accident, and states as follows: “Looking at all the circumstances I can come to no other conclusion than that the boiler gave way in consequence of the weakness of its construction, at a pressure not very much exceeding that at which it was ordinarily employed, and at a pressure under which it ought to have been perfectly safe.”

In the face of such powerful testimony as to the utter unfitness and dangerous state of the boiler, how a verdict virtually exonerating from blame all persons connected with the unhappy affair could be recorded, it would be difficult to understand, were it not that, in one important particular, with respect to the probable amount of pressure at the time of the explosion, Mr England, a practical engineer, entertained an opinion decidedly antagonistic to that of the government inspector.

When doctors disagree, who shall decide? The jury, perhaps, can scarcely be censured, under such circumstances, for refusing the grave responsibility which would otherwise attach to them by registering a verdict in accordance with the views explained by Captain Tyler; but it may well be thought that they ought to have expressed themselves a little more strongly against the carelessness, to speak mildly, that has undoubtedly been exercised by making use of an engine such as the locomotive in question, without first ascertaining and adopting suitable means to rectify the faults in construction which, in so lucid a manner, were pointed out by Captain Tyler; whose valuable suggestions, which ought not to have been omitted, relative to the careful testing of steam-boilers, cannot be too strongly commended to the notice of the proper authorities.

Accident at the underground railway, 21 June, 1862

For more than two centuries past, the River Fleet has proved a source of trouble and been a sad nuisance. Its resistance, at times, to being decently covered from the sight was vigorous; and at this time, notwithstanding its strongly arched prison, a dangerous and rebellious spirit is now and then shown, which will not be altogether curbed until the main intercepting drainage is completed.

For some time past there has been leakage either from the large Fleet sewer or the tributaries, which has lodged in the hollows near the schools below the church on Saffron-hill. This was not only unwholesome to the scholars of this school and the congregation of the church, but also to others, and clearly showed that there was some imperfection here which required remedy.

At the time of the construction of the Fleet sewer we noticed that there were considerable difficulties in forming the junctions in the neighbourhood of Hay-street, where the land descends at steep gradients from Ray-street, Hatton-garden, on the west; Coppice-row, on the north; and from Clerkenwell-green, Smithfield on the east, during the execution of the sewer works. We more than once saw the rush of storm-water after thunder; and it is not easy to convey an idea of the rush and strength of the water coming here from three quarters.

On Sunday last, and for some days past, there were sharp showers of rain, and the surface earth had been saturated to a considerable extent. One of the heaviest of these storms passed over Islington in the afternoon of Sunday; but before that time-about mid-day a length of the new wall inclosing the railway was seen to sink at the point above referred to.

It is said that at this time the more level part of the sewer was waterlogged. Part of the roadway fell, and the foul water of the Fleet came forth and flooded the railway works (which are here an open cutting) and several parts adjoining. It is fortunate that no loss of life has taken place: notwithstanding, the cause of this accident should be carefully inquired into, and an explanation given to the public; for uneasiness has been caused as to the danger of such floods when this railway is completed.

After this was written, namely, on Wednesday last, a further disaster occurred, resulting in the fall of a considerable length of retaining wall, about 25ft high, at the northern end of Victoria-street, and an influx of water. Prompt measures were adopted, and the sewer has been diverted temporarily.

See also:

>> From the archives: The construction of the Palace of Westminster, 1847

>> From the archives: Benjamin Disraeli’s proposal to hang architects, 1847

>> From the archives: The Crystal Palace’s leaking roof, 1851

No comments yet