Britain’s greatest architectural practice is planning a massive expansion. But what does it mean for the man who founded the business, the global brand and, of course, the buildings?

Foster + Partners, the largest and most internationally renowned British architectural practice of all time, is threatened by radical change. As revealed at the end of last month, Lord Foster plans to sell his 90% stake in the practice that he founded 43 years ago and is now valued at between £390m and £500m. Four private equity firms are bidding to take over the practice, which could fund the expansion of the practice to up to 30 offices around the world.

At present, Foster boasts about 850 staff, which makes it the world’s eighth largest architect. They are housed in just four offices, in London, Berlin, Hong Kong and Istanbul. The scale and rapidity of the expansion that is being planned would be unprecedented in the architectural world, even at the American giant, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. This is undoubtedly an exciting prospect, but it is also a dangerous one.

The threat is not to the size or strength of the market leader, at least not in the short term. Nor is it a matter of Lord Foster retiring. As the firm’s spokesperson says: “Norman’s going nowhere in the foreseeable future.” The threat is that the expansion would dilute the practice’s basic product, which is the quality of its design. And if that goes, so does the brand.

More than any other UK architect, Foster is a brand that keeps the firm in the public eye and attracts the multitude of clients who buy the products.

“Plenty of people all around the world associate Foster’s name with the Gherkin in London, the Reichstag in Berlin and other iconic buildings around the world,” says Robert Jones, director of brand consultancy Wolff Olins. “The same goes for the architect SOM and the engineer Arup, but Foster stands head and shoulders above them.”

So what is the essence of the Foster brand that is so highly prized but eludes other architects? It is certainly not specialisation in particular building types, as the practice has tackled virtually every one and has even ventured into city planning, bridges, public squares, pleasure yachts, tables and taps.

Nor has it shown a special fondness for cultural buildings, the traditional preserve of elite architects. Its first art gallery, the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich, was not completed until 14 years into the life of the practice. If anything it has, from the Reliance Control factory of 1966 onwards, embraced lowly industrial, commercial and spec office buildings.

Rather, the Foster brand is the product of its creative design approach. The practice still piously adheres to the modernist doctrine of form following function, truth to materials and the quest for new technologies. No less modernist, it tackles each project from first principles. And it carries through each job with a rigorous design logic.

The extraordinary result is that building types are revolutionised under the Foster touch. The Willis Faber Dumas office block of 1975, for instance, was the first building in a town centre to be sheathed in frameless glazing. During the day, the smoked glass reflects the surrounding buildings; at night the interior lights up like a shop window.

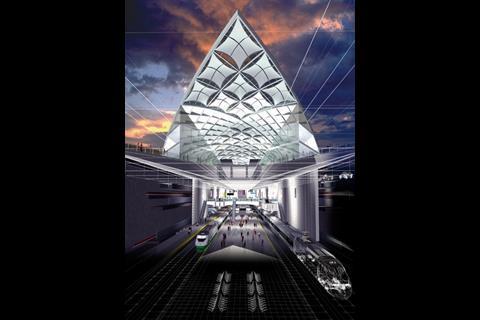

Before it was colonised by chain stores, the Stansted air terminal of 1991 gave travellers uncluttered space and daylight all on a single floor by pushing baggage handling below decks and condensing services and signage in structural trees.

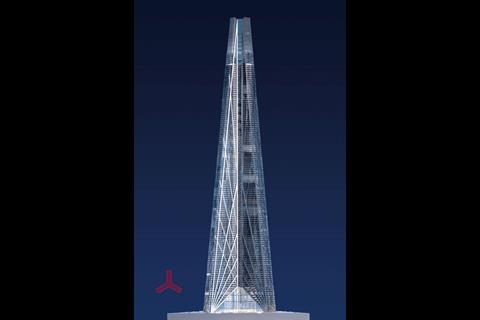

The Swiss Re office building of 2004 transforms the rectilinear office tower into a curvilinear cigar with opening windows for natural ventilation.

Despite the range of the practice’s output, a discernible Foster style runs through them. There is nothing so crude as a repeated shape or motif, as in Will Alsop’s blobs on sticks or Frank Gehry’s curly sheathing. Nor is there a flurry of high-tech gizmos, as in the Lloyd’s building by Lord Rogers. Rather, the Foster style is an updating of Mies van der Rohe’s dictum that less is more. Space, function, shell, structure and services are all distilled into a single, clear-cut, deceptively simple form that changes for each building.

The big question is whether the Foster brand, and the distilled design approach it is based on, can survive the sale and expansion of the practice

At the Sainsbury Centre of 1978, for instance, external envelope, structure, services, toilets and entrance lobbies are all neatly contained within a perimeter zone of constant width. This leaves the main floor area free for exhibits.

The big question is whether the Foster brand, and the distilled design approach it is based on, can survive the proposed sale and expansion of the practice. Will the rigorous design logic be watered down by the diffusion of the practice into 30 offices spread around the globe?

The firm’s project design is based on logical reasoning rather than mystical inspiration, so it’s true that it can be successfully taught to architects straight out of college. At the same time, though, the design process for each job is kept on track by a central design review panel based in London and chaired by Lord Foster himself. This stimulating yet disciplined control system could well be stretched too far by the expansion of the practice.

There is the problem of introducing external funding through the proposed sell-off. To Tim Quick, who was a project director at the practice until he joined Halpern in 2001, the sale comes as no surprise. “The practice has never been frightened of the commercial world,” he says, “and Norman’s catchphrase was that architects complaining about clients was like sailors complaining about the sea.

“Even so, I don’t think the sell-off would create a healthy environment. He who owns the company will call the shots, just as Rupert Murdoch does with his editors.”

For financial backers, the temptation would be to steer the practice towards commercial projects that replicate an established formula. There are already signs that this is happening. Tower blocks commissioned by entrepreneurs, whether for offices, residences or hotels, are establishing themselves as the dominant building type.

The expansion poses another threat. If it does lead to a dilution of the design process, this could demoralise staff, who up till now have been held together by Foster’s creative vision and design integrity. Many may leave, further threatening design quality. This would also blur the distinct Foster brand, which is more vital to a firm with buildings and offices spread thinly across the globe.

To Robert Jones of Wolff Olins, “Brand is absolutely essential to bring in the long-term economic return. Investors have to ensure that the brand is maintained and keeps developing. The worst thing would be to churn out replicas.”

Looking at the inevitable weakening of Foster’s role in the firm and the eventual retirement of the 71 year old, Jones says: “Fosters really is a one-man brand. The advantage is that it has a strong identity, but the disadvantage is that this is associated with one man. The changes offer the opportunity to create a brand beyond the man, so that it continues to develop and grow after he retires. They need to build something bigger and wider. They need to bring other architects forward, preferably young ones and with slightly different points of view. The story’s got to keep moving.”

Identifying Foster + Partners with a global brand invites comparisons with big names in the fashion world such as Versace or even celebrities such as Madonna and David Beckham. And a chain of offices around the world could be likened to Starbucks. The danger with the celeb phenomenon is that, as in the Celebrity Big Brother debacle, popular adoration can flip into mass contempt.

Jones takes a more sanguine view of architectural branding. “There is a similarity here, because all these firms and individuals are becoming central to public life,” he concedes. “But the last thing architecture is is ephemeral. There is little danger of instant life or death as in a fashion house. Foster + Partners has a long way to go before it joins the Beckham category.”

Reassuring, indeed. But is Britain’s all-time greatest practice about to take its first step on a slippery slope?

Postscript

For more Foster projects and news, go to www.building.co.uk/archive

1 Readers' comment