Covid-19 may have emptied our cities during 2020 and changed the way some staff do their jobs for ever, but reports of the death of the office are premature. Continuing our series on rethinking design in the wake of the pandemic, Dave Rogers looks at how office design is adapting to create spaces people will want to return to

Rethinking design series: Offices

Last month, a former chairman of the National Trust wrote a column for a national newspaper suggesting that the office block had had its day. Simon Jenkins, a former editor of the Evening Standard and The Times, wondered whether office workers now needed office blocks. “When the coronavirus has passed,” he told Guardian readers, “I believe the truth will be revealed.” In other words, no.

Jenkins, it seems, will not be mourning the end of the office block. “It has to be good news,” he went on. He wrote of a decade of London non-planning which meant that hundreds of speculative offices were in the pipeline, most of it “probably useless”.

He will no doubt have been buoyed by the news that the amount of new office space being built in the middle of London collapsed in the past six months as the impact of lockdown, jittery developers and staff working from home all helped put the brakes on schemes. The latest London office crane survey from Deloitte showed just 2.6 million ft² began in the period between April and September – a fall of 50% on the previous six months.

Deloitte says the central London market, which stretches from White City and the West End in the west, through to the Docklands and Stratford in the east via the dominant City of London, was “in a state of suspension as business occupiers pause to reflect on what the future of working will look like and how this might impact future workplace requirements”.

New construction activity in the Square Mile fell by 60% to 1.2 million ft² across 10 schemes, compared with the 2.8 million ft² being built across 16 schemes in the previous period.

Unfortunately for Jenkins, the end of the office block has not come in time to save the Square Mile from being landed with the “monstrous” 22 Bishopsgate. “The biggest and ugliest block in the City,” he wrote. “Perhaps one day it will be occupied by squatters.”

Sir Stuart Lipton and Peter Rogers, the veteran developers behind the tower, were probably not going to invite him to the ribbon-cutting ceremony anyway. But what if Jenkins is wrong?

Perhaps his view is coloured by his age. He turned 77 in the summer and, for some, whether you believe in the future of the office or not can be largely down to how old you are.

You can’t build a culture over Teams. [Firms] are trading off a culture built up in the workplace – 500 people can’t just meet each other over a functional process like Teams

Nigel Webb, British Land

James White helped to set up office architect specialist March & White a decade ago. The firm is due to finish work on 60 London Wall this month and previous schemes have included, among others, carrying out a makeover a few years ago to Lipton Rogers’ offices at Cavendish Square behind London’s Oxford Street.

“Demographics come into it,” says White, adding: “Different age groups want different things. Younger people want to be in the office, building their careers, making connections and getting the mentoring support. It’s not so easy for them to be working from home where space is restricted. They want a social feel at work. If you can design and create space that hits people’s needs, you are going to bring them back to the office.”

A recent study by ISG, carried out in September, found that those groups known as Millennials and Generation Z – in effect, people born between the early 1980s and 2010 – suffered the most from home working, with 32% saying that productivity had fallen and 62% citing poor home working conditions. The survey also found that employees would like to spend three days in the office to optimise productivity rather than the 2.5 days a week anticipated by employers.

Inside the office of the future

So, what does the office of the future look like? Dan Drogman, co-founder of office tech specialist Smart Spaces, says the real estate industry has had to embrace smart technology because of covid-19. He points to a 400% increase in enquiries between March and October this year compared with 2019.

Drogman adds: “Air quality is generating a lot of interest, as indoor air quality is understood to play an important role in fighting the spread of covid-19 in buildings. Smart building technology can help proactively monitor the levels of contaminants present in the built environment and manage the air flows and fresh air ratio in a building.”

Beate Mellwig, workplace practice leader at HOK’s London studio, says: “It is important to investigate ventilation and filtration systems and determine what works best for the building. Spaces intended for groups can include carbon dioxide sensors in order for ventilation increases along with occupancy and carbon dioxide levels.” Mellwig says that more touchless features should be incorporated through implementation of internet-of-everything technologies. “These would enable more hands-free, voice-activated systems to safely manage the return of workers while minimising the risk of disruption due to infections.”

The sheer range of apps, sensors and touch-free interfaces can be confusing, prompting a recent report from the British Council for Offices which highlighted that it is the integration of these technologies that is key, a harder task for retrofits than new-builds. But Nigel Miller, managing director of Cordless, author of the report, sees compelling reasons to invest in tech: “Choosing to incorporate technology into the way we build and design offices will help us solve some of the most challenging questions our industry faces: around health but also on sustainability.”

These are the sorts of findings that Iain Parker, one of the partners at London QS Alinea – which has made its name working on towers in the capital, including 22 Bishopsgate – says mean the demise of the office has been overplayed. Offices, he adds, will continue to attract and retain talent, helping to build a company culture that no amount of Zoom or Teams calls can replicate.

“After 9/11, everyone speculated that it would be the end of tall buildings. It didn’t happen. Designs were adapted, as were operational procedures around things like security, but the world has continued to build tall buildings at a significant pace. I believe the same concept will be true of offices.”

But things will change, that much people do agree on. Whether it be more naturally ventilated buildings, a reduction in occupation densities, more automation in communal areas and socially distanced desking and meeting rooms, what the office looked like before covid-19 will undoubtedly be different once the pandemic is over.

Developer British Land is one of the biggest in the London office market. It was behind arguably the most celebrated landmark tower of recent years, the Leadenhall Building, better known as the Cheesegrater, designed by the practice of Richard Rogers – whose 1970s Lloyd’s building the Cheesegrater sits opposite and which was handed the highest architectural protection, a grade I listing, nine years ago.

British Land is also redeveloping the 1980s Broadgate complex further north up Bishopsgate. Higher up still, where the City bleeds into Shoreditch, tower cranes have been up since the summer at a mixed-use site called Norton Folgate, designed by Stirling Prize winner Allford Hall Monaghan Morris.

Its head of development, Nigel Webb, says the £300m scheme, due to be carried out by Skanska, is slated for completion in 2023. “It’s one of our priority next phase projects,” he says, adding the firm pressed on with the Cheesegrater when the City was gripped by another global crisis – the financial implosion that threatened to sink the world economy more than a decade ago.

“The design plays to a post-covid world. It’s still early days for clients, but we are hearing they want to get back to the workplace.”

Webb says the gloss has been taken off the working-from-home honeymoon as the unexpectedly warm and sunny spring, followed by a largely balmy summer, gave way to the traditional wind, rain and dark nights of autumn. Winter has barely started and suddenly the prospect of more months working from a kitchen table, a bedroom or a spare room – if people are lucky – does not seem quite so appealing, especially when the curtains are being drawn in the afternoon.

“The longer this goes on, the keener people are to get back to the workplace. People miss that social interaction over autumn and winter,” he adds. “You can’t build a culture over Teams. [Firms] are trading off a culture built up in the workplace. We’re trading off the fact that we know each other and collaborate – 500 people can’t just meet each other over a functional process like Teams.”

For larger companies, certainly, the office is one part of its sales pitch to would-be employees. Given the choice of working on an out-of-town industrial estate or a well-appointed modern office, most would choose the latter.

Felicity Lindsay, a London-based real estate law specialist at Canadian law firm Gowling WLG, says: “Larger companies especially still derive a significant level of brand equity in the market from their office buildings. Those offices also provide a sense of belonging and community to employees, which in turn leads to increased engagement levels.”

Barry Jessup, a director with First Base, the mixed-use specialist co-founded by Stuart Lipton’s son Elliot nearly 20 years ago, agrees and says offices remain a destination for many “performing a crucial role as a place of collaboration, idea creation and learning”.

He adds: “Occupiers recognise that the space they keep is a direct reflection of their brand and crucial in retaining talent.”

Larger companies still derive a significant brand equity in the market from their office buildings. these offices provide a sense of belonging

Felicity Lindsay, Gowling WLG

British Land says it is looking at smart technology such as touch-free access systems for Norton Folgate and purification systems for the air-conditioning. And yet, for all the niceties of working in a smart office – as opposed to a bedroom or kitchen table – and for all the hi-tech changes that will no doubt be ushered in by covid-19, there is one big problem that developers cannot quite as easily overcome: the commute.

“The biggest challenge is that people have enjoyed the extra time and not spending extra money on fares and being crammed on trains,” British Land’s Webb concedes. Jessup adds: “None of us likes to commute and we all want a working environment that blurs seamlessly with our personal lives.”

Webb says the working day will move more into shift patterns, with the traditional nine-to-five day being overtaken by staggered starts. “That was becoming a trend. What covid has done is accelerate those trends and put a greater emphasis on working from home.”

Being able to cater for flexible working, then, is what occupiers will want from their offices. Elliott Sparsis, the vice-president of real estate at Convene, a US-based workplace provider with two offices in London, says: “We have seen big names such as Google, Twitter, BP, Schroders, PwC and Standard Chartered taking active steps or publicly state their intentions to offer their employees more flexibility over how and where they work in the long term.”

He adds: “We believe there will be three places to work: the traditional central HQ, home and a third space, with all three operating seamlessly and technology being at the forefront of this transition, ensuring that firms can blend in-person and digital working.”

Getting in and out, up and down

Vertical transportation is a vital service in almost any office and in taller buildings in particular. A report by the British Council for Offices, Thoughts on Lift and Escalator Design and Operation After Covid-19, outlined how the need for social distancing has reduced the number of passengers that can use a lift car and limited the occupancy of buildings.

Mask-wearing has been made compulsory, hand sanitising stations set up at entry points and cleaning operations improved. Lift floors have been marked to show allocated space and required orientation of passengers and disposable objects provided to press buttons where hands-free operation is impossible.

Physical changes to systems have included increased mechanical ventilation to dilute airborne contaminants, vents in lift shafts and installing air-treatment systems to reduce contaminants and sterilise lift-car surfaces. Control systems with touchless operation have also been introduced.

Design features for new systems are now the priority. Ensuring adequate space to maintain social distancing in any new pandemic is leading to a reconsideration of the size of reception areas and lift lobbies, as developers weigh up the costs and benefits of providing larger spaces. Key design recommendations for new office buildings include:

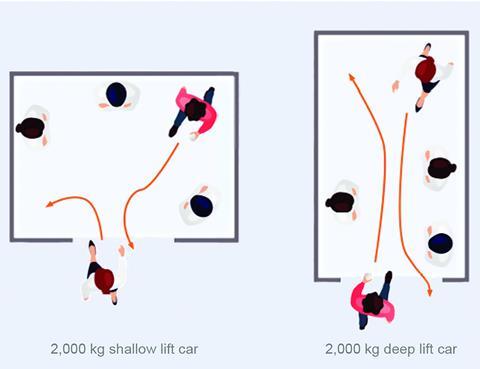

- Selecting wide, shallow lift-car configurations in preference to narrow, deep cars. This allows faster loading and unloading and easier social distancing (see diagram below).

- Ensuring minimum lift lobby dimensions are provided.

- Selecting doors at least 110cm wide to allow easier access and exit.

- Installing mechanical ventilation fans in all cars and fresh-air ventilation to all lift shafts.

Information compiled from a briefing note for the British Council for Offices, August 2020

And the Deloitte survey, while not good reading for them, makes it clear that offices will still remain key for companies.

It adds: “The office building will become a focal point for the business, where interaction with new and existing clients can take place. It is also likely to become a space to promote and support the wellbeing of employees, many of whom have faced isolation during the lockdown period as well as challenging working conditions. The office space will be intended to drive employee creativity and innovation and will be essential to attracting talent in the future.”

If one area of the UK has come to represent the traditional central office HQ more than most, then it is the Square Mile in London. The recently completed 22 Bishopsgate has added another 1.3 million ft² to the market, but when will it be filled?

A midweek trip into the Square Mile during the second lockdown resembled the City on a Sunday. If not quite dead, the area was eerily quiet, with office workers being easily outnumbered by construction workers.

But the chair of the City of London Corporation’s planning and transportation committee, Alastair Moss, is confident that the Square Mile will not be empty forever. “There’s not been a flight from the City,” he says.

“People will come back, but who knows what the trigger will be. There will be an end to this [covid-19] in the relative short term.”

Moss says one thing that will attract people back is the realisation, as one lockdown was succeeded by an easing of restrictions only to be replaced by another, that people need to work alongside each other. The novelty of working from home in shorts and T-shirts has worn off. “We are social animals. Industry and trade have continued throughout the pandemic.”

He says the City needs to diversify – although he adds that the City cluster, the clump of towers including the Gherkin, the Cheesegrater and 22 Bishopsgate, will not be joined by residential blocks any time soon.

Moss wants to see a greater emphasis on retail, leisure and culture, adding that is why the City approved Foster + Partners’ Tulip tower tourist attraction, a public inquiry into which wraps up next week before secretary of state Robert Jenrick decides whether to give the go-ahead or not.

Still building

The firm’s chairman is bullish about the continuing importance of the City as a place to work. Patrick Wong says: “English is not going to be replaced as the international language of business anytime soon.

“The British legal system will continue to remain the most trusted anywhere in the world. And, with the news that Oxford university in collaboration with AstraZeneca is leading the charge to develop a vaccine, it is hard to escape the fact that the UK is an intellectual powerbase.”

He adds: “The pandemic has led to questions about the long-term future of the office; however, we believe that it presents an opportunity rather than a threat to the office.

“The ‘right’ office space will become more important than ever, as will the flexibility we as business owners offer the workforce. London, like every major city, will play its part in the great global rebuild and, with its fine embedded qualities, will once again shine through

British Land’s Webb says the whole of the City is “on a journey, it’s working its way through a different set of uses. It’s becoming a softer environment and it will move to a seven-day economy, where at the moment it’s still five days a week.”

Alinea’s Parker adds: “The City will have to reinvent itself somewhat, attracting a slightly different demographic of workers including more tech companies and other sectors such as healthcare and life sciences.”

At some stage in the future, Moss and his colleagues at the Corporation of London will be running the rule over more towers planned for their borough. British Land is behind a scheme drawn up by Danish practice 3XN at 2 Finsbury Avenue at Broadgate while Hong Kong developer Tenacity has recently submitted plans for two 30-plus storey towers at 55 and 70 Gracechurch Street at the southern end of Bishopsgate, designed by Fletcher Priest and KPF respectively.

The firm’s chairman, Patrick Wong, is confident that the City, London and the UK in general will not see its appeal wane in the light of covid-19. “The UK, especially the City of London, will continue to be a centre for international investors. We are in no doubt [the UK] will bounce back from covid-19.”

When they do get built, one firm that might be involved with their construction is Morgan Sindall, whose fit-out business, which includes Morgan Lovell and Overbury, raked in £839m of income last year – more than a quarter of its total £3bn revenue.

Morgan Sindall’s chief executive, John Morgan, says that it will be two or three years before the long-term future of the office is decided. “I’m sure we’re not going to have a situation where people sit in offices five days a week,” he adds.

“The idea of sitting in a row of desks is unlikely to survive. Offices will have to be really nice to attract people back in.”

With the talk of successful trials of vaccines and now a UK licensing, hopes are rising that some sort of normality might be just around the corner. But others are less sure that workers will come flooding back straight away.

“I think it will be the end of next year,” says Flan McNamara, the man who helped to develop the Shard when he was at Sellar. “They will be less densely occupied, meaning the cost of occupation will be higher.

“The way we engage with them will be different. It could be a drop-in version of the way we are working now.”

Right now, though, no one can say for sure how things will be. “We haven’t,” McNamara cautions, “found what the new product is yet.”

Rethinking Design Series

This article is part of an ongoing series looking at how different building types are changing in response to the pandemic.

> Rethinking Design: How the pandemic is transforming healthcare

> Rethinking Design: Housebuilders’ initial responses to the pandemic

No comments yet