Supermarkets don’t like to be beaten on price - or on their environmental credentials. To get ahead of the competition, Tesco is now testing every bit of green kit it can lay its hands on to build zero-carbon stores. Building reports on the savings

Winning the hearts and minds of shoppers with warm and friendly environmental claims has become a fierce battleground for the big supermarkets. They are all jostling for position, trying to prove that the food on the shelves comes from more sustainable sources than the competition’s, that waste is driven down to the bare minimum and that energy use is as low as can be. This is a big challenge because producing food on an industrial scale, transporting it and keeping it fresh until the consumer walks out of the shop with it has a massive impact on the environment.

The claims are more than just hot air, as the supermarkets are serious about reducing their environmental impact. An important part of this strategy is building more environmentally friendly stores. The biggest player, Tesco, has a target of being zero carbon by 2050 with an interim target of reducing its emissions by 50% by 2020 compared with 2006 levels. This includes all the energy used in stores such as refrigeration and other equipment. It also includes the environmental impact of leaking refrigeration gas, which can contribute up to 25% of the emissions of a typical store. Tesco is tackling this challenge with the same clinical efficiency that characterises its store expansion programme. It rigorously assesses building products for environmental performance, then carefully monitors how well these perform in finished supermarkets. Kit that performs well gets incorporated into the next round of supermarkets in a process of constant refinement. Given that the company spent £1.6bn on its store expansion programme last year, it has a very good idea of what works and what doesn’t. So what is the process, and what has Tesco found?

The brand plays on

Back in 2007 the company set itself its zero carbon targets and the first “environmental store” opened in Cheetham Hill in Manchester in 2009. It achieved a 70% carbon footprint reduction and created a distinctive “look” for the company’s environmental stores. “It was a great success and looked fantastic,” beams Martin Young, Tesco’s chief architect.

“There is still a need for Tesco to be a brand and we wanted to build something brand identifiable. This has a strong brand identity, which we have evolved.” This evolution culminated in the first zero-carbon store at Ramsey, Cambridgeshire, which opened at the end of 2009. Lessons learned from this have been taken forward to the latest stores, including Bourne in Lincolnshire, which opened this February.

Product evaluation starts with a thorough assessment of the products’ performance and embodied carbon content. It looks at a huge range of products including controls, pumps, low flow rate taps, phase change materials, renewable technologies and “every LED under the sun”. More than 170 products were evaluated last year.

Tesco doesn’t take anything on face value, so it visits factories and looks for independent verification of product performance. It also has its own set of data, which allows it to do like-for-like comparisons. It refuses to use Building Regulations data for the carbon content of electricity and calculates this itself instead. It has baselines for embodied energy, and products must better these to get through. Other criteria ensure products will be acceptable to customers and staff, look good and be durable. Solutions also have to be capable of being installed quickly to keep in with tough build programmes and must be cost effective. Manufacturers must be capable of delivering sufficient volumes and do this when needed.

Products are also assessed against other solutions - for example, there isn’t much point looking at products that collect condensate from fridges if it is easier and cheaper to install rainwater harvesting systems.

Bukky Bird, Tesco’s head of sustainability, says not much gets thrown out by this process. “We very rarely reject things, we just ask difficult questions,” she explains. Tesco only evaluates products it reckons have a decent chance of making the grade because it doesn’t want to stifle innovation. Many companies will develop products specifically for Tesco because of the potentially high sales volumes, and the supermarket giant doesn’t want to put them off.

Once a product makes it through this process, it is ready to be used on a store. Only stores that can make the most of what the product offers are selected. New products can demand new specifications - for example, LED lighting was used for the first time at the Ramsey store for illuminating the car park and petrol station. Ensuring the user experience remains the same can be tricky due to the different output characteristics of LED lighting compared to conventional systems. Some new products are trialled on more than one store to iron out the way these might be handled by users. After the store is completed, the product is evaluated to see how well it performs. For example, can staff use it easily? Does it deliver the claimed outputs? How much maintenance does it need? Is it delivering the claimed energy savings?

Carbon cutting

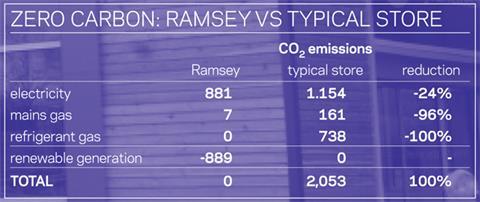

So what has Tesco found? It completed the Ramsey store in December 2009, so has a year’s worth of performance data. Energy used for heating, ventilation and cooling was 66% less than the 2006 baseline store. Appliance power was reduced by 44% and the use of carbon dioxide as a refrigerant cut emissions by 69%. Overall the store produced 889 tonnes of carbon dioxide compared with 2,053 tonnes for the 2006 baseline store. Those carbon emissions were offset by using a CHP unit running on biofuel made from waste vegetable oil.

Although the store is zero carbon, Tesco found some elements didn’t work as well as predicted. The CHP system suffered from 11% downtime compared with a prediction of 5% but Tesco says this was down to site-specific that won’t affect installations in other areas. Tesco has taken CHP on a stage at Bourne by fitting a CCHP unit that uses waste heat to power absorption chillers. It is firmly behind CHP technology and fits it to many of its other stores, although these are mostly powered using gas.

More energy was used than predicted by the sales area’s lighting. “We realised we could have done a lot more with the lighting,” says Bird. Roof lighting is supplemented by electric lights but these could switch off more often in response to strong daylight. Bird says Bourne features a better controlled lighting system that should help but the long-term answer is to fit a light-sensitive cell to every single light fitting for maximum efficiency. “We are talking to suppliers about this,” says Bird. She adds that LED lighting is used in back-of-house areas and for illuminating food in chilled cabinets but the technology hasn’t advanced to the point where it can be used for lighting sales areas.

Future work includes optimising existing systems - for example, by using better controls and zoning back-of-house cooling and ventilation systems. The company is also using fat to power its CHP systems. It collects 140,000 litres of chicken fat a month from its stores and reckons this could power a couple of installations. One is already up and running and will be monitored for a year to make sure it delivers the required energy output and doesn’t cause any maintenance issues. Looking forward, the company is investigating aerobic digestion systems to recover energy from waste food.

Renewable technologies are already used on stores; Bird says Tesco is evaluating which type of PV system offers the best combination of cost and output but so far no one type has an edge. The company is also looking at the Solyndra PV system where the modules are wrapped around tubes rather than lying flat on the roof, to see if this offers better performance.

The company is also trialling phase change materials in back-of-house training rooms to see if these help reduce the need for mechanical cooling when the room is occupied. “We’ve done the assessment and found for our application we won’t get the performance claimed but we still think they are worth trying,” says Bird. “I don’t think phase change materials will really rock the boat but every little helps.”

What a green Tesco looks like

The 25,000ft2 Tesco in Bourne, Lincolnshire, is one of the company’s latest environmental stores and is zero-carbon. Like several earlier stores, this one features a glulam frame, which Tesco says is liked by customers. It gives the store a warm, natural feel which is enhanced by light streaming through the rooflights in the sales area and the glass front overlooking the car park. Bird says the store isn’t particularly well insulated and like other new stores has an airtightness rating of three. Better insulation and airtightness means more internal heat gains, which means more energy is needed for refrigeration. In other respects the store looks fairly conventional including the terrazzo flooring, which is time-consuming to install. “We would like to use something else but can’t find anything that works as well,” sighs Steven Fricker, Tesco’s construction project manager.

Fridges have sliding doors that stop cool air draining out and eliminate the need for cold catchers at the bottom of the fridges, with the associated fans and ductwork. The LED lighting inside the cabinets does a good job of lighting the contents.

The back-of-house areas feature a steel frame rather than timber. “It’s more economic to build it out of steel because of all the plant on the roof,” says Fricker. “If we used wood it would still need reinforcing with steel to take the loads.” All the refrigeration plant in the store features CO2 refrigerants.

Super-fast programmes are the name of the game with supermarkets and Tesco’s environmental stores are no exception. The back-of-house facilities, including the training room and toilets, come as modular units; the CHP plant is also a modular unit, as are the services.

Fricker is constantly looking for ways of cutting down on programme and is looking at a cassette system for the walls and roof of the next environmental store which will be built in Cefm Mawr in Wales. This is a Howarth Timber system that comes complete with insulation, waterproof membrane, rooflights and sunpipes already installed.

“It will take three weeks off the seven-week programme for the frame,” beams Fricker. “It goes up to 12m high which means it is suitable for all our stores.”

No comments yet