Want a three-storey extension to a grade II-listed building in less than a day? Or a house that’s been digitally manufactured to be as easy to assemble as an Airfix model? Martin Spring visits two projects that are taking off-site manufacture to the next level

The manufacture of Bell Travers Willson’s Digital House was entirely computer controlled – right down to the screw holes

The Digital House, or half of one, opens this week at the Architectural Foundation in central London. The house is not digital in the avant-garde sense of arrestingly wonky forms sculpted by computer. Actually it’s not unlike a traditional London terraced house. What is digital – and quite revolutionary – is the way it is made.

The house is the creation of Bell Travers Willson, a four-person architectural practice that has been going for two-and-a-half years. The three partners all cut their teeth at Foster + Partners, but whereas Alastair Travers and Nick Willson are both qualified architects, Bruce Bell is a Royal College of Art graduate in digital product engineering.

Bell is dismissive of most recent attempts at off-site prefabrication, claiming that their manufacturing methods are anything but advanced. “The £60,000 house systems are not very well integrated,” he says. “Most rely on structurally insulated panels, which is just a raw material, and you need to bore all the holes on site.”

“If you want to learn from the aircraft or automotive industries, you’ve got to take on their systems in which design and manufacturing are fully integrated.”

Which is exactly what Bell Travers Willson has done with its prototype Digital House.”All the components in our house are fully computer modelled complete with all fixing holes and routes for services,” says Bell.

The practice’s integrated system is the product of research and development – another essential ingredient of the aircraft and automotive industries – that stretched over two years and was sponsored by a grant from the London Development Agency. It also relies on a vital piece of kit – a computer numerical control (CNC) router that the practice’s housebuilding consortium, Facit, bought for £30,000.

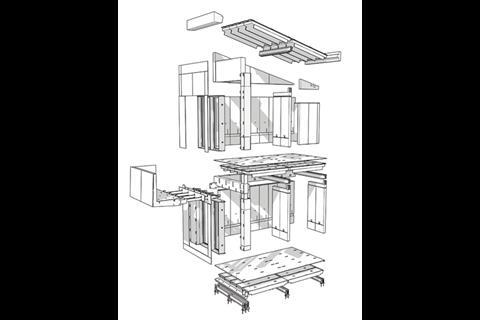

It is the CNC router that carries out all the computer-controlled manufacture of the house. It cuts flat plywood sheets into complicated patterns that contain the DNA of the system’s design. Once that is done, the house is just clipped together with as little skill as a Lego kit, firstly by creating modular hollow box components, or cassettes, and then by assembling the cassettes on site into the finished building.

QS Kevin Bonfield calculates that the construction cost of an infill terrace house of 125m2 is £155,059, without VAT but including all professional and planning fees. This equates to a unit cost of £1,240/m2, which is higher than a typical £60k house of £784/m2. However, Bonfield claims it is up to 22% less than an equivalent terrace house traditionally built in concrete block and render.

Bell Travers Willson has no intention of selling off its computer-manufactured housebuilding system. Instead it offers its own package deal through Facit, which it has set up with associated furniture maker, Dominic McCausland, and visualisations and marketing consultant, Andrew Goodeve.

As with any other package deal, Bell Travers Willson offers clients a one-stop shop rather than the risky procurement process in which design and production are fragmented between consultants and contractors. “We try to simplify the process,” adds Bell. “We also offer a quality architectural design, high-precision construction and speed of delivery at a cost less than traditional construction.”

None of this is likely to lead to architect-led mass housing production. “New technologies are so much more flexible,” says Bell. “You can change cutting patterns by the flick of a switch. So what we offer is relatively bespoke design linked to digital manufacture that is called ‘mass customised’,” (see pictures).

The practice now hopes to make deals with clients ranging from one-off owner-developers, through commercial property developers to housing associations.

Building a digital house step by step

1. Digitally cutting the material

Digital design and manufacturing is all packed into the first stage of the construction process of the Digital House. The key piece of kit is the computer numerical control (CNC) router, which is basically a conventional timber jig, although one linked to an advanced digital 3D control console. The intricate patterns needed to fabricate a timber cassette can be cut in 10 minutes, including interlocking joints, internal spacers, service holes and assembly screw holes. These can be cut out of a standard 2.4 × 1.8m sheet of structural grade plywood to a tolerance of ± 0.1mm. The router is small enough to be transported to and housed on site.

2. Fabricating the cassettes

After the CNC router has done its work, the rest of the construction sequence is remarkably low tech. The house is a kit of parts that is assembled just like an Airfix model. The parts making up all the floors, walls, roofs and columns are plywood cassettes. These are each in themselves a kit of parts, with all the pieces coming ready-formed off the CNC router. The pieces fit together with interlocking halving joints and are simply banged together with a carpenter’s mallet. As the precision cutting of the router ensures a tight fit, no glue is needed, although the boxes are screwed together to increase rigidity.

3. Laying the floor plate

No fiddly setting out is needed. Instead the construction of each storey begins by laying a plywood floorplate complete with holes that are precisely located to take the wall cassettes.

4. Assembling the cassettes

As they typically measure 2,400 × 600 × 236mm and weigh just 23kg, the modular cassettes can be easily handled by two operatives. Each also comes with its reference number engraved in the plywood by the router, so it can be easily located on site. To fix a cassette, you simply remove the front panel, screw the side panel to its neighbour and refit the front panel. The primary beams have to carry higher loadings, so they are not cassettes but conventional timber and plywood beams in triplicate.

5. Insulation, servicing and finishes

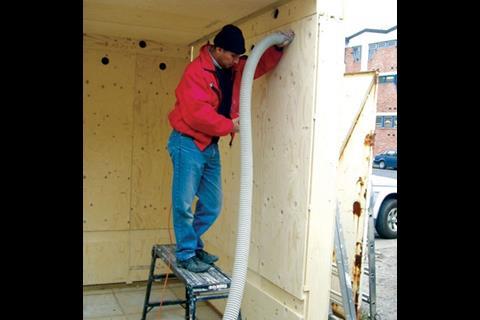

Once the shell is assembled, the cavities of the cassettes are filled with blown cellulose insulation. Electric cabling is run along recessed trunking, and water and drainage pipes are threaded through floor voids. Doors and windows are fitted, and the shell is finished with conventional plasterboard panels on the inside, timber boarding or some external cladding on the outside, and a roof finish, such as zinc sheeting. The whole prototype house is assembled in four days.

Downloads

‘Mass customising’ digital manufacture

Other, Size 0 kb

Postscript

Making the Digital House is on view at the Yard Gallery, 49 Old Street, London EC1 until 20 March

No comments yet