In 2012, the UK construction industry faced up to an onslaught of cuts, U-turns, stalled projects and financial collapses, while also demonstrating how to put on the greatest show on Earth. Building looks back on an extraordinary year

In a year that gave us no let-up in the flow of bad news, one event was conspicuous in its positivity. The London 2012 Olympic Games were a huge success, not just for our athletes but for the UK’s construction industry.

From the moment it was announced that London intended to bid to run the 2012 Games, the industry had to endure the scepticism of the great British public - represented in spades in the national press.

Commentators pointed, with admittedly some justification, to projects such as Wembley stadium, and claimed that the Olympics would highlight not our strengths but our weaknesses.

Such critics were silenced. The Games opened in July with a ceremony that highlighted the depth and diversity of our history and culture, in a stadium and park that highlighted to the world the best of British.

While the following review of a year in construction inevitably dwells on some of the less triumphant tales in what is still an industry facingenormous challenges, this should not detract from the resourcefulness and dedication that delivered the Olympic park on time and on budget. Letthe retrospective games begin …

Golden moments

The year began with a huge boost to the morale of the UK construction industry. On 9 January, the Olympic park - complete with all the main venues - was handed over to the Games organisers, followed by the athletes’ village on 27 January.

The biggest of the venues, the main stadium, was designed by Populous and built by main contractor Sir Robert McAlpine with structural and services engineer Buro Happold. The 80,000 capacity stadium was completed in March 2011, less than four years after ground was first broken in mid-2007.

The Zaha Hadid-designed aquatics centre was also completed in 2011 by Balfour Beatty and Arup, alongside the velodrome, basketball arena, handball arena and the international broadcast centre and main press centre. The beginning of 2012 saw the completion of the athletes’ village, subsequently rechristened the East Village, creating some 2818 new homes for east London - 1,379 of which will be affordable.

The Olympic Delivery Authority’s (ODA) success was not achieved without challenge, with the athletes’ village proving most problematic. Main contractor Lend Lease subcontracted half of the plots to other contractors, including Galliford Try, Sisk and P Elliott, the latter of which subsequently went bust.

Galliford Try then became embroiled in legal wranglings with some its subcontractors, the fallout of which continues to cause controversy. However, the fact that the village, the park and its venues were handed over on time and on budget is still testament to the professionalism of the ODA and its contractors.

The only downer for the firms involved was that their ability to trumpet their achievements to the world in the hope of winning lucrative foreign contracts was hampered by strict marketing rules set by the International Olympic Committee.

Our Building 2012 campaign highlighted the case and it was taken up by MPs, industry figures and trade bodies such as the RIBA and the Institution of Structural Engineers, but the government admitted in August that no solution to the problem would be found before the end of the year.

Eyebrows were also raised over the 33% pre-tax profit achieved by CLM, the private sector delivery partner for the Games, between 2006 and 2011, as revealed by Building in August. A joint venture between Laing O’Rourke, CH2M Hill and Mace, CLM made a pre-tax profit of £162m on a turnover of £495m. Industry figures claimed the high margin was achieved due to efficient delivery and a lowering of costs following the 2008 crash.

More good news

Good news for the construction industry, if not for some Cotswolds home owners, came this year in the form of the government’s commitment to the HS2 rail project.

The unequivocal government support and ring-fenced public funding HS2 has enjoyed is in marked contrast to interminable political prevarication over aviation expansion and the austerity cuts being imposed in other sectors.

The £32.7bn 119-mile railway between London and Birmingham is expected to create up to 10,000 construction jobs, boost the West Midlands economy by £2.5bn and indelibly integrate high-speed rail into the country’s transport network and urban fabric.

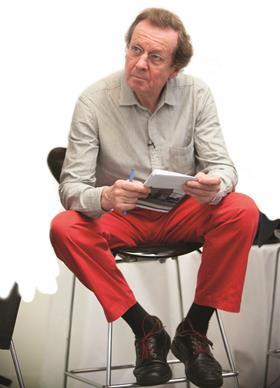

There was success of an unusual kind for architect George Ferguson. A former RIBA president, Ferguson (left) became Bristol’s first executive mayor in November following an unexpected victory.

While turnout was low at 28%, independent Ferguson achieved victory with a margin of more than 6,000 votes.

June marked a positive step for London’s Battersea Power Station when a joint venture including Malaysian developer S P Setia was

named the preferred bidder to buy the station from administrators Ernst & Young after a £400m bid. The sale was completed later in the year after which the first detailed planning permission was sought.

The project received a boost in the Autumn Statement when the chancellor announced a £1bn guarantee loan to fund an extension to the Northern Line to the site.

No comments yet