B&Q has tucked a store brimming with renewables onto a site less than half its usual size. Kristina Smith reports on how the design team did it.

Rising up the travelator towards B&Q’s New Malden store, shoppers pass three posters proclaiming the building’s green credentials, including its use of geothermal energy to provide heating in the winter and cooling in the summer. It’s a bit of a shock, then, when a wall of heat hits you as you enter. The temperature is 34C at floor level and a sweltering 37C above head height.

“It’s so hot, I can hardly move,” complains one wilting shop assistant. “There’s supposed to be underfloor cooling but there’s a fault with it.”

Anthony Coumidis, director of McBains Cooper, which advised B&Q Properties on the installation of geothermal and other sustainable technologies, thinks differently. He believes the store operators, driven by the bottom line, are reluctant to spend money on running the heat pumps.

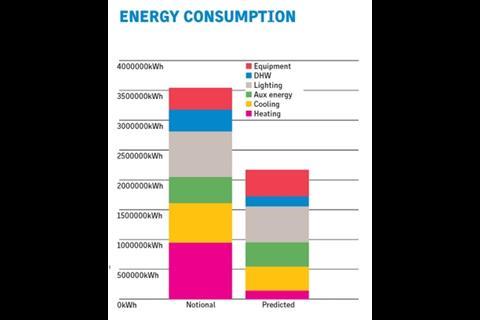

It is perhaps understandable that there are bedding-in problems – whatever the cause – in a building such as this. It’s a retail shed, but not as we know it. B&Q has pushed the boat out with a range of environmental technologies at the southwest London scheme, including solar panels and photovoltaics, a wind turbine, rainwater harvesting, natural lighting and a small sedum roof. It’s both a statement and an advert for some of the store’s products.

It also represents a significant move on B&Q’s part to consider shoppers’ comfort: “The philosophical approach in thinking of the internal environment created for the customer is quite different to some retail buildings that have been designed to reduce energy,” says Paul Hinkin, managing director of Black Architecture, which designed the building. “This is a move from top-down to bottom-up conditioning strategy, looking to condition the lower areas only.” Traditionally B&Q stores are heated by gas-powered blowers suspended from the ceiling and have no cooling provision.

It doesn’t look like a B&Q store, either. Instead of a warehouse fronted by a vast car park, this store is set on a compact site (1.8ha compared with the standard 4ha) with parking on two levels beneath it. There is a cafe and small retail units and, in an effort to shake off its reputation as a builder’s store and compete for women customers with Ikea and Homebase, heavy products are separated off at the back.

Motorists passing on the A3 can look through the glass-box frontage and see people and trolleys moving between floors on travelators. A 35m tower sports a wind turbine on top as well as the B&Q.

B&Q Properties had not always intended to build such an exemplar of sustainability. It was well advanced with a design based on its Sutton store, near Croydon, when the planning rules changed: the Greater London Authority was given powers of strategic consultation on major planning applications and raised concerns about the scheme. The Merton rule, requiring 10% on-site renewable energy, also came into play.

Black Architecture, which had researched a B&Q concept store with reduced energy use, greater land efficiency and lower impact materials, was called in. “Our brief was to look at the site afresh,” says Hinkin, who designed the award-winning Sainsbury’s eco-store at Greenwich while with Chetwood Associates (see box overleaf). “We were asked to come up with a feasibility study and concept design that could address the issues of mixed use, sustainability and the Merton rule.”

Heat aside, one of the first things you notice in the store is the natural light coming through north-facing rooflights. Black’s original plan was for rooflights only over the till area but McBains Cooper, which was appointed because of its record on sustainable and particularly geothermal technologies, and its lift expertise, carried out a cost-in-life calculation to show the energy saved by using them throughout.

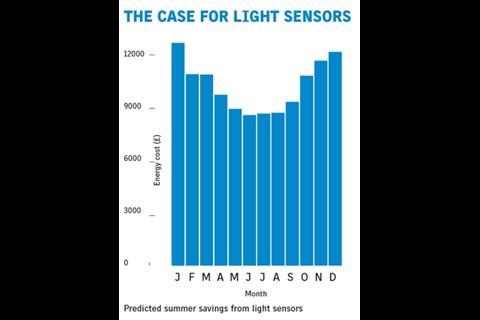

Part of the savings comes from the use of dimmers, linked to sensors, which turn the high-frequency T5 luminaires down or off in bright conditions (see bar chart attached). The lights were on when BSD visited on an extremely bright day, however. Coumidis wondered whether the system had been manually overridden during the night shift and left that way.

McBains Cooper also had to make the cost-in-life case for the underfloor heating/ cooling proposed by Hinkin, comparing it with B&Q’s usual suspended gas-fired warm air heaters. B&Q also costed the option of water-to-air heat pumps suspended from the ceiling, using heat from the geothermal system. This would have had a lower capital cost (see table 1, above right). Using geothermal energy for both heating and cooling makes sense, says Coumidis, because during the summer when heat is being moved from the building to the ground, the earth is being recharged.

“If you are designing a system for heating only, in general they are not cost-effective because you need to space the boreholes farther apart,” says Coumidis, who designed the system to deliver 18-20C in winter and 5-6C cooler than the outside temperature in summer. “In summer, I could not substantiate the design to a particular temperature. As long as you feel 5-6C cooler than outside, there is a perception of cool. As human beings, we can accept 7-8C difference comfortably.”

There were also technical issues to address. B&Q has a particular slab structure to take the high loads and movement of forklifts, and does not usually have a screed applied. However, the pipework for the underfloor heating had to sit within a screed, usually 75mm below the surface. In this application, the pipework sits beneath 100mm of screed so that the screed won’t crack and when staff drill bolt holes for fixing shelves in new positions, there is no chance of creating a leak.

The original design called for energy piles, where the piping for the geothermal heating pipe goes within the concrete pile, effectively turning it into a heat exchanger. Simons Construction, the main contractor, rejected this system because it would have delayed construction as the piles take longer to install and the pipework must be tested post-installation. Instead, the decision was made to have deep boreholes which the specialist contractor Geothermal International installed under an area of the car park, so they did not impact on the building construction programme.

We have always championed the inclusion of photovoltaics and wind power. These technologies can only grow and develop

if people are investing in them

“Simons had no experience of geothermals,” says Coumidis. “Going for energy piles would have meant I was messing around with the civils and structural stuff. As it was, I was messing around with their slab.”

There are 108 boreholes, 100m deep below the car park, interconnected to two separate fields to provide resilience. Five heat pumps on a common header deliver up to 650kW of heating or 440kW cooling.

The 14,500m2 building’s other sustainable technologies are perhaps more valuable for what they say about B&Q than for what they save, although water bills will be cut by the rain harvesting system designed and installed by Stormwater, which will supply the toilets and garden centre. The Genersys solar water heating, which provides hot water for the toilets and kitchens, is an encouragement to customers to buy the kit.

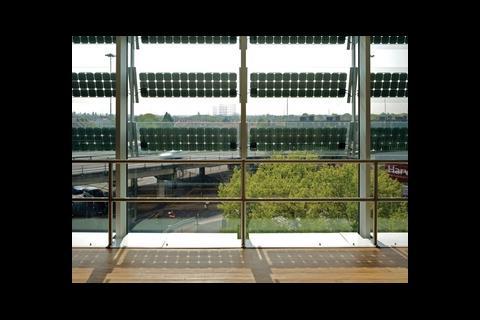

The Romag glass-laminated PV panels were originally intended to cover an area of roof equivalent to that of a three-bed semi, but McBains Cooper suggested moving them to the windows of the cafe so they could act as brise-soleil. It works well, and makes the technology visible to shoppers. The electricity they produce is small but enough to power the two pumps which circulate the water through the boreholes.

“To produce enough electricity to power the store, you would need to cover most of the roof,” says Coumidis. “And then you are talking about 70-80 years’ payback. You only use PV when you are desperate and need to get the points [for BREEAM].”

Hinkin has a slightly different take on PV: “We have always championed the inclusion of PV and wind technology. There are a lot of discussions about payback. These technologies can only grow and develop if people are investing in them. But you don’t design a standard building and pepper it with technology to address the environmental sustainability box.”

The wind turbine, said to be the largest building-mounted one in the UK, is a lot meatier than the pretty helical one first planned. It would have produced only a few kW of electricity whereas the Ropatech system chosen can give 20-30kW on a good day. In fact, says Coumidis, it was whizzing round rather too fast for the structural engineers’ liking and causing vibrations in the tower, so a brake had to be fitted.

Not surprisingly, cost control has been challenging and value engineering has struck several parts of the project. “Cost was a big issue because it was way over budget at the beginning,” says Coumidis. “We had to bring it back to something affordable.”

Retrofit option

Part of the original design was for low-level mechanical ventilation, delivered up through the building’s columns, which would be opened on hot days with some of the rooflights to create a natural stack effect. Although the rooflights will open and create some air flow from the garden centre door, the low-level mechanical ventilation is not there. The way has been paved for retrofitting, however.

How much did all the eco-technology add to the standard store build? “The question you should be asking is, how much is the land?” counters Hinkin. “This is prime retail land on a major corridor into London. You would probably need to buy twice as much land to build a standard store.”

As well as being an effective advert for B&Q, the New Malden store will provide it with valuable data. It is already considering other sites for eco-stores. As for the mystery of the missing underfloor cooling, this is solved the next day when a call to the duty manager reveals that engineers are fixing a software problem. He adds that Simons Construction has not yet fully handed over the building, which opened in March. The BMS is a self-learning system, so for a while things may not perform as they should when conditions are outside expected parameters.

The duty manager is proud of the building and its radical heating and cooling system: “This is the first time this has ever been used in any B&Q. And the weather has been unusually hot, so you would expect they would have to tweak the system.”

Sustainable stories: 10 years on

When Sainsbury’s at Greenwich opened in 1999, it was hailed as a blueprint for sustainable supermarkets. Like B&Q’s New Malden store, it was designed by Paul Hinkin, now managing director of Black Architecture.

The B&Q is a different proposition to Sainsbury’s – it’s bigger and it is non-food retail – but Hinkin has used the same principles to try to create a comfortable environment for shoppers while being kinder to the environment.

The Greenwich store is heated through the floor by waste heat from a CHP plant and cooling comes from air being drawn in at ground level and breathed out through the roof. The New Malden store has the first large-scale geothermal heating and cooling system in retail.

At Greenwich, glass rooflights were used to allow for automated louvres to protect certain foods and for them to be closed at night to prevent the “black hole” effect for shoppers looking out and light pollution externally. The B&Q rooflights are a cheaper polycarbon material because they cover a much larger area. They are translucent, so there is no black hole effect and light transmission is reduced.

What could we see in the next Hinkin-designed store? “I would relish the challenge of looking at timber in the retail environment,” he says. “Rather than engineered timber structures, it would be interesting to look at something far lighter with smaller members.”

Downloads

Cross-section

Other, Size 0 kb

Source

Building Sustainable Design

No comments yet