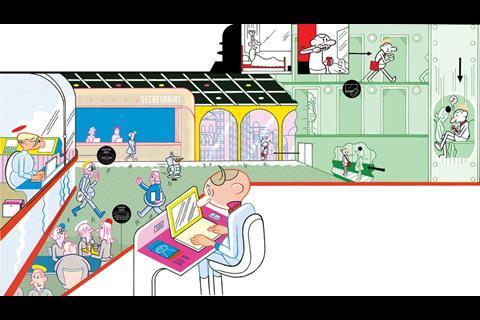

Ignore those iPod-toting Tweeters at your peril. They are the office users of the future. Emily Wright reports on how both commercial and residential design will have to adapt to the lifestyle of the Facebook generation

Young people today. They are always hooked up, plugged in and online. Tweeting, instant messaging, My-spacing, Facebooking, they are the generation that is digitising the dictionary. They will also be the people investing in and inhabiting office space in the next 20, 10 or even five years. The ceaseless online activities of teenagers (yours or other people’s) might drive you to distraction, but there is no escaping the fact that they are the occupiers of the future.

Thanks to the technology they have grown up with, however, most are unlikely to spend five days a week in the office. Providers of commercial design and development need to cater for their needs if they want to stay up with the play.

Social networking tools such as Twitter and Facebook, along with gadgets like the iPad, enable fast, effective communication on the move. You don’t need office space or a meeting room to use them. “When we all started our careers, work was what happened in the office,” says Richard Kauntze, chief executive of the British Council for Offices (BCO). “If you weren’t in the office, you weren’t working. Those boundaries have been completely blown apart by technology and it is clear that, while there will be demand for commercial office space in the future, this space will take on a very different form.”

What this form will be and its implications for commercial design and development were the subject of a huge discussion at this year’s BCO conference in May. Delegates agreed that the Facebook generation, which has grown up surrounded by technology, 24/7 communication and social networking, is likely to be the catalyst for a rapid change in office design.

“They talk to 20 people at one time while playing video games, listening to music and doing work,” said architect and past president of the RIBA Jack Pringle at the conference. “It is this generation that will set the agenda for the office of the future.”

The death of the traditional office

The future of office design is already being explored by some forward-thinking firms such as Microsoft, Google and BT. At BT, 30% of employees are either full- or part-time home workers. These organisations have moved away from banks of workstations to a more flexible hot desk system coupled with larger social areas such as cafes, equipped with bigger tables to accommodate laptops and wi-fi.

This focus on social spaces is expected to be the linchpin of successful office buildings. If people can file a report or do a job from anywhere in the world, what they will want from an office is somewhere to make human contact. John McRae, director of architect ORMS, explains: “It is human nature to want and need interaction. We are seeing a growing trend for lounge areas rather than rows of desks in offices, large spaces where people can get together.”

This move towards a more social work environment is expected to accelerate over the next 5-10 years in response to the needs of future users - those now in their teens and early 20s. Stuart Bowman, divisional director at consulting engineers Hurley Palmer Flatt, says: “Your sons and daughters will be the people demanding office space in 10 years. This generation is exceptionally connected - all the time, wherever they are. And this will affect the way they work. We grew up working with eye contact and handshakes and for that we needed space.

That won’t be the case in the future.

“We almost need to survey a load of 16-year-olds and find out what they want and what they think the future of working life will be.”

These thoughts are echoed by BCO president Gary Wingrove, who is organising next year’s conference in Geneva, themed around future office design and development. Wingrove is concerned that the industry is not interacting enough with young people and fears some developers and architects are not adapting office designs quickly enough. “We need to listen to what the next generation is saying. Because in real terms, people who are thinking about investing in a new building now won’t be moving into that building for maybe six years.”

The inevitable changes should be taken into account in buildings being designed now, Wingrove warns. “By the time offices being designed now have got the go-ahead and been built, we will be several years down the line,” he says. “By then, the people working in these spaces will be the ones currently doing their degrees. They will probably still want to come to a place to meet and sit down, but you don’t need to provide banks of desks to do that. All you need is a large open space, flat surfaces of various shapes and sizes, and wi-fi.”

Wingrove may be right, but if the rise of the technology inspiring these changes tells us anything, it’s how quickly the Facebook generation can adapt, move on and change direction. While talking to young people about what they want in the future may help, it won’t be enough to inform the industry what the sub-25s will want in five years’ time.

“There is no doubt that commercial space in the future will need to take on a different form,” says the BCO’s Richard Kauntze. “The problem is identifying what form that will

be. So it is vital to design these buildings with as much flexibility built in as possible. I see a successful future commercial office space being one that can be quickly adapted to meet a need that may be entirely unexpected.”

Some in the industry are already catching on. Lee Polisano, director of PLP Architecture and one of the architects behind the design of the Heron Tower, agrees that flexibility is the key to creating office space that will remain relevant. “Many organisations still need offices, to gather people, to enable interaction,” he says. “But now we need to be more mindful about how we design these spaces. We need more adaptable buildings.”

Polisano explains how the Heron Tower has been designed to achieve just that. “The design is all about facilitating social life in the work place, about offering flexibility,” he says.

“Different areas of different sizes and different temperatures to suit the people operating within them rather than just a cookie cutter, repetitive block. Adaptability is what will be attractive to people in the future.”

Ian Eggers, a director at Mace who worked on More London and the Shard among other commercial projects, says: “We have a great opportunity to adapt design and development of commercial space in this lull - or crash as some might call it. The industry really needs to look hard at what people want now and I think a return to a simpler system might be the answer. You don’t need the most intrinsic, complex office building in the world to provide more touch-down spaces and social areas, which is what I see people wanting in the future.

“People are looking harder at value and these sorts of simple, brick-clad office buildings that are forced to work harder are likely to be more attractive now. If we could design the Shard again, would it be done in the same way? I don’t think so. There’s no future for enormous, glass skyscrapers.”

Ken Baker, managing principle EMEA at international architect Gensler, says: “New builds are considerably easier to work with than historical or older real estate when implementing new technologies. We do see a trend leaning towards smaller floor plates - take Heron Tower and the Shard - and this has its pros and cons. Large floor plates enable more collaborative workstyles, whereas the smaller plates tend to divide departments and employees… An architect’s role is to navigate around these challenges in order to produce the best possible

client solution.”

Closer to home

Changing attitudes to work and evolving office design will affect homes and residential developments, too. As people increasingly work from home, developers and architects are seeing rising demand for studies and self-contained offices.

Robert Adam, director of ADAM Architecture, says the shift away from commuting five days a week is already having a marked effect on residential design. “People say that to work from home all you need is a spare room, a computer and a plug. But as this trend increases, people want more separation. We’re now putting more studios above garages as more people are asking for an office space with a separate entrance to the family home.”

He believes local services will need to adapt as home increasingly becomes a place of work as well as one of leisure: “I think we’ll see the demand for coffee shops in local communities rise. Possibly even for auxiliary services like secretarial or printing shops. We are working on a masterplan for a residential development in Princes Risborough in Buckinghamshire and we are proposing a local hub, some sort of serviced facility where people can go to work.”

Adam believes design that takes account of these changes will be more attractive to buyers: “The people buying the houses that are being designed now will be working from home quite considerably. I think a serviced facility of some sort could give residential developments of the future a real edge. It offers people something they want. Plus it’s good for local communities, family life and the environment as it cuts down on travel.”

He says architects and developers ignore this growing trend at their own risk: “Society is changing and anyone, particularly architects, who thinks they are setting trends is in cloud cuckoo land. We service major changes to society, we don’t make them. And if you miss them, then you miss out.”

Tony Dowse, chairman of Environ Communities, a developer in the south of England, agrees. He has already radically updated his firm’s approach to residential design to respond to the rise of the home worker: “Every single house we’re designing now has a home office or, if it’s not big enough, space to create a work area,” he says. “We can use sliding doors and moveable walls to make sure these spaces are proper work areas.”

Demand is on the up, he says, and in larger house developments he too is seeing a rise in requests for self-contained offices, usually above garages, with their own entrance points. “I don’t think a lot of developers are focusing enough on the fact that people are not commuting into the office five days a week any more. If you have two similar house types on the market and one has an office or work suite, that will be the clincher.”

Craig Casci, director of Grid Architects, is working on a residential development in Harrow, north London, where the integration between home and working life is even more pronounced.

Honeypot Lane (or Stanmore Place as it is officially known) has been designed with young start-up professionals in mind and has everything they might need to work from home. The £31m scheme includes more than 700 mainly one- or two-bedroom bed flats on the same development as a block of living-room-sized office units complete with IT support and business advice. Casci says this gives residents a clear path to grow their business, the third phase of which is the opportunity to move into a self-contained office with moveable walls.

“This development gives people the chance to start small and then move into bigger spaces when appropriate without having to go further than over the road,” he says.

Complete residential developments such as Honeypot Lane, tailored to home working rather than a commute to an office, could become one element in a whole new order dedicated to giving people as much flexibility as possible in their working week.

Most industry professionals agree that the new order will still include offices and commercial spaces, but the most successful will have maximum flexibility built in. One thing for sure, though, is that changes need to be made.

As Casci points out: “The sub-25-year-olds will work anywhere and everywhere, are always on some form of instant messaging system and yet are highly productive as a result. It’s the most amazing paradox. It may be new to us. We may not be able to understand how they can keep up with so many distractions, but they do and this is how the world of work, and so the design of offices and homes, will adapt. The industry’s biggest mistake would be to ignore this phenomenon.”

2 Readers' comments