Thirty years ago, Prince Charles’ infamous attack on the proposed National Gallery Extension pretty well assigned the project to oblivion. To mark the occasion, here’s a collection of other grand construction projects that, for good or ill, never saw the light of day

Thirty years ago last month Prince Charles made a speech that changed the face of British architecture. In the ornate surroundings of Henry VIII’s sumptuous Great Hall at Hampton Court Palace he dropped into an otherwise routine oration the incendiary and now infamous word “carbuncle” when describing then current proposals for the National Gallery Extension. The rest, as they say, is history: the prince’s role as Chief Antagonist to the Architectural Establishment was born and the modernist hegemony that had defined British architecture for the past 30 years was broken.

One of the more forgotten casualties of that evening’s revolutionary invective is the original so-called carbuncle itself. Designed by architects Ahrends, Burton and Koralek, their competition-winning scheme had already attracted intense criticism from planners and the public before Prince Charles’s intervention. Even Peter Ahrends himself was forced to defend it at an extraordinary press conference held on the eve of planning submission.

But after the Hampton Court speech the writing was on the wall. It was eventually thrown out at public inquiry a few months afterwards before being replaced seven years later by Robert Venturi and Densie Scott Brown’s Sainsbury Wing, a much safer, if rather limp, post-modern crowd pleaser.

The infamous incident is useful for illustrating just how many grand plans are aborted. London’s history is littered with thousands of major projects that never saw the light of day, the inevitable consequence of a city that has nurtured a bullet-proof capacity for prevarication. Elsewhere too, great abandoned enterprises present a fascinating alternative history of what might have been.

So in order to commemorate the anniversary of the original National Gallery Extension’s royal execution, we have assembled a collection of

similar construction projects that will forever remain on that great drawing board in the sky.

Lutyens’ Liverpool Cathedral

Outside London, Liverpool is rare among English cities in having two major cathedrals. But in 1930, plans were afoot to embellish the record even further by giving the city the second biggest cathedral in the world after

St Peter’s in Rome. Ever since the Irish influx caused by the Great Irish famine in the mid-19th century, the local Catholic diocese had planned a great new cathedral to serve the city’s large Irish immigrant population. Pugin began one in 1853 but diverted funds meant it was never finished. By the thirties, money was no longer a problem as Liverpool was a flourishing industrial port so plans were resuscitated on an even larger scale. Although seminal modern classicist Edwin Lutyens had only designed two churches and was more associated with banks and country houses, his spectacular recently completed government buildings in New Delhi were seen as striking the right tone between solemn reverence and monumental awe and he won the commission.

Lutyens didn’t disappoint, his design for the cathedral was stupendous (pictured left). Built in granite and brick and dressed in a combination of Byzantine and classical styles to separate it from the more Anglican Gothic, it would have had the largest dome in the world (51m diameter compared to 34m and 42m at St Paul’s and St Peter’s respectively) and at 160m high, would have been the tallest building in the UK at the time. With a footprint of around 20,000m² and space for 10,000 worshippers, it would have been the largest single-volume building ever built in Britain.

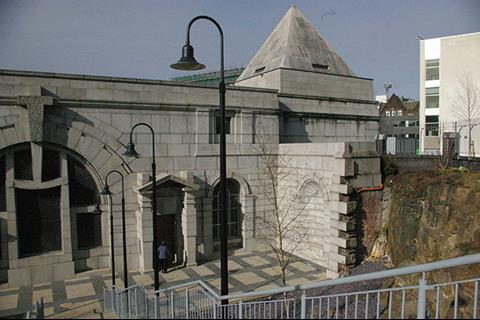

Construction commenced in 1933 and continued steadily despite the Great Depression. But it was the onset of the Second World War which sounded the death knell. Costs were initially set at £3m, but with wartime restrictions these spiralled to £27m, about £1.13bn today, an untenable sum during a prolonged state of national crisis. Although the crypt was completed in the fifties (left), Lutyens’ cathedral was never to rise further. Its replacement was Sir Frederick Gibberd’s space-age wigwam of 1967 which was built entirely and somewhat surreally above Lutyens’ barely-exposed crypt, a circumstance which renders the current cathedral virtually free of its own foundations.

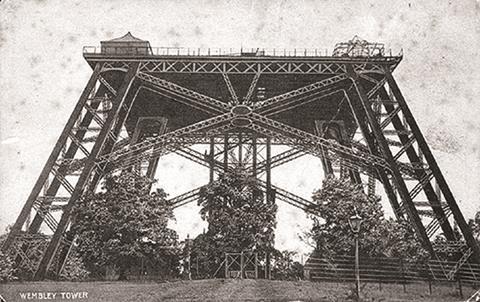

The Wembley Eiffel Tower

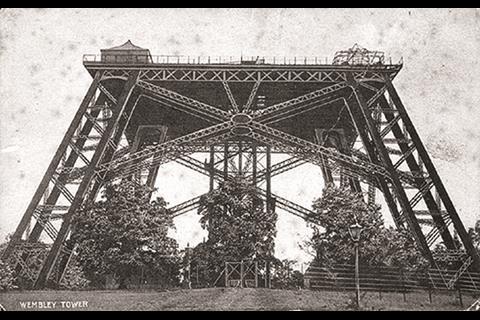

The ancient rivalry between London and Paris is arguably the world’s longest running game of civic one-upmanship. Historically, architecture has always leant itself as the most conspicuous battleground for this competitive self-aggrandisement to be fought. Paris’ Panthéon was inspired by St Paul’s, Waterloo Place was inspired by the Place de la Concorde, Haussmann’s boulevards were inspired by the Regent’s Park terraces and so on. But this rivalry must have reached its preposterous peak in 1891 when construction began on London’s answer to the Eiffel Tower. The Wembley Park Tower was a lunatic riposte to the completion of Gustave Eiffel’s tower two years earlier. For half a century London had prided itself on having the tallest monument in both cities, the 170ft Nelson’s Column. This title was snatched away in spectacular style when the 984ft Eiffel Tower was completed, an intolerable provocation which left London’s Victorian elite seething with jealousy. A counter-attack was inevitable and it came in the shape of MP and railway engineer Sir Edward Watkin’s vainglorious Wembley folly.

Watkin had form for flights of fancy; in 1869 he had incurred the wrath of Crown commissioners by failing to seek permission for digging a vast hole in the Kent coastline in his bid to build a tunnel to France. As we now know that wasn’t an entirely outrageous idea but the tower proposition was conceived on an altogether grander delusory scale. Watkin’s competition-winning design was virtually identical to Eiffel’s, a tapering open lattice-work of riveted iron. At 1,150ft, it had the obligatory height advantage over Paris. The tower was to be the centrepiece of a new pleasure park which Watkin, as chairman of the Metropolitan Railway, had already ensured had a brand new station, Wembley Park.

When construction began concrete foundations 35ft deep were dug to support the tower’s weight of 3,000 tonnes. However, work progressed sluggishly and after three years it had only reached a height of 155ft. It was never to rise any further, insufficient funding and the turning tide of public opinion ensured that all work stopped in 1894. The tower was left as a rusting abandoned stump until it was finally blown up in 1907.

Great Victorian Way

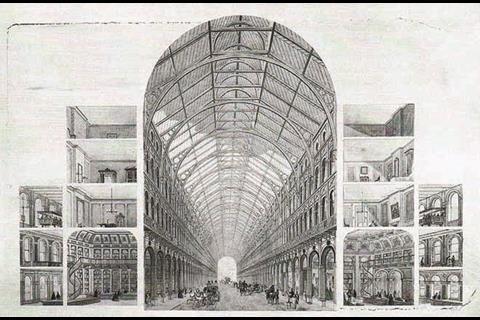

The Victorians are well known for their visionary ambitions, but plans rarely got bigger than this. By 1855 seminal engineer Sir Joseph Paxton was riding high on the runaway success of his Crystal Palace, centrepiece of the wildly popular Great Exhibition of 1851. Seeking to capitalise on his success he proposed an even more ambitious plan, an orbital covered railway around central London. But this wouldn’t have just been a railway; the idea was that the tracks would be incorporated within a grand, multi-storied arcaded structure which would also include shops, a road and housing. The structure was to be 108ft high, (taller than Westminster Abbey, England’s highest nave) and 72ft wide with the soaring central arcade covering a road encased underneath a spectacular glass barrel vault. It would have looped around central London like a giant girdle for 10 miles, with the intention of relieving the congestion problems that were as much a feature of Victorian London as they are today.

Accommodation was to be built on either side of the road with the elevated railway occupying an upper level. There would have been four tracks on either side incorporating express and stopping services. Paxton estimated that it would be used by 105,000 passengers every day and that a half-orbital railway journey would take just 15 minutes. In a piece of sci-fi ingenuity that pre-empts the vacuum train technology being developed today, Paxton also proposed that the trains would be propelled by air pressure pushing the trains through a tube rather than by conventional steam engines.

Parliament was supportive and deemed the proposal a “remarkable novelty”. But it was eventually scuppered by the familiar scourge of costs. Paxton estimated that his vision would cost £34m in 1850s prices, roughly about £4bn today. The plans were eventually abandoned. But parliament and several railway companies had been mesmerised by Paxton’s idea of an orbital urban railway system. The genius of Paxton’s idea came to fruition eight years later when the opening of the tube meant that London did actually get the world’s first orbital railway but one that ran under the city rather than above it. And in a final homage to Paxton’s vision, the Circle Line roughly follows the route of his Great Victorian Way.

The South Bank Crystal Palace

How do you solve a problem like the South Bank? Its panoramic riverside promenade of theatres, galleries and street performers offers one the capital’s most vibrant urban experiences. But the South Bank is also gloriously dysfunctional and its development history has been chequered by some unfavourable urban detritus: elevated walkways, dark under crofts, poor connections, undeveloped spaces, fragmented ownership and tonnes of concrete.

Jubilee Gardens offers a case in point. This premium riverside open space has now finally been developed into an attractive landscaped park. But for decades it stood empty and unkempt, trapped in a municipal paralysis where local landlords, the Shiriyama Corporation, owned the subsoil but the Southbank Centre owned the grass, thereby fuelling a quixotic London-esque stalemate that stymied its revitalisation and stood as a metaphor for the wider development frustrations across the estate.

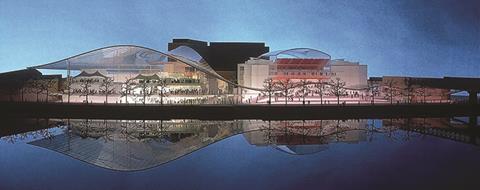

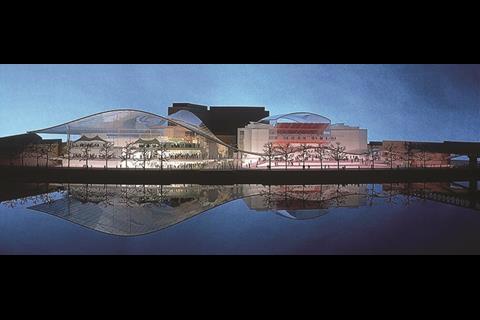

But in 1994, Richard Rogers thought he had found the solution. His practice won an international design competition to regenerate the area and proposed covering much of the South Bank under a giant glass canopy. Inspired by Paxton’s Crystal Palace, the canopy would have wisely swerved to avoid the Royal Festival Hall and the National Theatre but deliberately concealed the grisly brutalist triumvirate of the Hayward Gallery, Purcell Room and Queen Elizabeth Hall. It would have been a spectacular gesture, a giant glass wave unifying a disparate assortment of blocks.

Alas, it was not to be. Despite securing over £10m in grants, the scheme became a victim of the Arts Council’s inability to agree on a development strategy for the area. However, in the intervening years, elements of the Rogers scheme have been realised here and elsewhere. The Royal Festival Hall has been refurbished and new amenities have been introduced to the riverside walkways. The concept also came to life in Washington DC’s 2010 Arena Stage by Bing Thom Architects where two theatres were enclosed under a unifying roof structure.

Two decades on the squabbles over the South Bank’s future remain with Feilden Clegg Bradley’s latest redevelopment proposals postponed. Interestingly that project’s contentious attempt to increase commercial area was also a feature of the Rogers scheme which sought to expand usable area by 300%.

No comments yet