Maccreanor Lavington’s Blackfriars Circus for Barratt Homes does everything a scheme centred on a 27-storey residential tower can do to engage with London’s architectural heritage – including bringing in a new public square and courtyard spaces. But can a tall building in London ever be traditional, asks Ike Ijeh

Of the host of social, economic, cultural and urban criticisms levelled against luxury high-rise towers in London, one of the most pressing is that tall buildings are not indigenous to London’s townscape composition, that they are somehow alien to the core character and identity of the city. Skyscrapers are central to New York’s metropolitan image in the way that canals are synonymous with Venice and gauche casinos are interchangeable with Las Vegas. But, despite high-profile and frequently controversial additions to London’s skyline in recent years, tall buildings – particularly residential ones – often seem to be out of kilter with the deep-rooted architectural themes and traditions woven into London’s historic identity.

But what if a tall building actually sought to engage in the history, tradition and materials of London’s architecture and public realm? What if a tall building was less concerned with its status as a vertical object and was more interested in immersing itself into the horizontal sweep and rhythm of the capital’s streetscape? Essentially, what if the design of a tall building in the capital, for the very first time, attempted to be an organic product of London’s urban and architectural traditions rather than a superimposed threat to them?

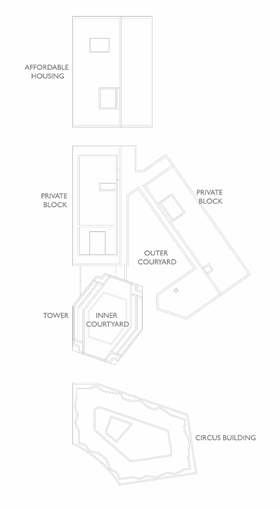

This is the ambitious task set by Maccreanor Lavington’s latest project. Blackfriars Circus is a residential-led mixed-use scheme for housebuilder Barratt Homes on St George’s Circus in Southwark, south London. Although its keynote feature may indeed be a 27-storey residential tower (called Conquest tower), it also encompasses four other mid-rise buildings extending up to 10 storeys. The 1.02ha development provides 336 private and affordable flats as well as 3,000m² of workspaces for small to medium-sized business enterprises.

So far so good. But most of the features on this checklist can be found on scores of residential developments across the capital. What makes this one different and how can it lay claim to representing a new and specifically London typology of residential tall building?

Also read: Residential towers - through the roof

Also read: Residential construction markets - how do London and Melbourne compare?

Street and circus

For practice co-founder Gerard Maccreanor, this project has its roots in the rich history of its surrounding context. “It’s all about reinstating the circus and re-establishing Blackfriars Road as an important boulevard between Elephant and Castle and the river.”

The first Blackfriars Bridge opened in 1769 as only the third crossing across the Thames after London Bridge and Westminster Bridge. As part of its development Blackfriars Road was laid to its south, stretching arrow straight – an unusual feature for London – towards St George’s Circus. Another unusual feature, to modern eyes at least, was the level of civic ambition this location once aspired to, a characteristic Maccreanor is keen to restore.

Not only was the circus itself originally laid out as a rotunda lined by concave facades in the formal Georgian tradition, but also Blackfriars Road itself was once illuminated by hanging torches that would dramatically herald visitors’ approach to London. Even as late as the 1930s, Elephant and Castle just to the south of the circus was celebrated as the “Piccadilly Circus of south London.”

The decline began with rapid industrialisation in the 19th century followed by wartime bombing in the Second World War which left severe scars of poverty and deprivation throughout the borough. Heavily bombed Blackfriars Road became a kind of urban no-man’s land, its wide pavements lined with anonymous post-war office blocks that would turn their backs to the street. By 2012, when Maccreanor Lavington was appointed, only one original building was left on the circus with the remainder being incongruous modern blocks that largely ignored its defining circular geometry.

Not so anymore. The new building edge reinstates the original curved line of the circus and presents a series of glazed punched double‑height openings that face directly onto it. These openings are part of the plinth that extends across the street facade on Blackfriars Road, picked out in glistening glazed brickwork that differentiate it from the chalkier tones above. Additionally, entrances and shopfronts now line the ground floor continuously, its new frontages and uses reanimating the street with activity and energising public realm.

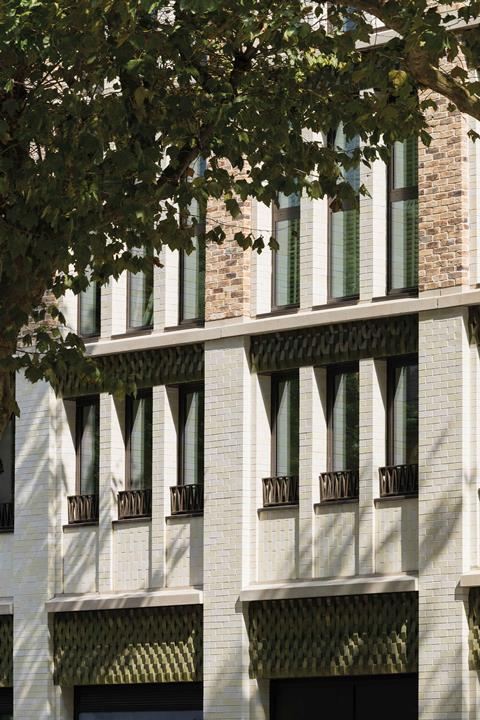

Brickwork

Brickwork is perhaps the material most synonymous with London, but it is not a material commonly applied to tall buildings in the capital. “There have been a few and it’s an area in which practices like Allies and Morrison have also done a great deal of work,” says Maccreanor. “But these other examples are normally lower buildings clad in precast brickwork. Barratt’s methodology uses in-situ brickwork so that’s what has been done here. And we believe that this is the first instance where brickwork has been used in this manner on a London building this tall.”

Maccreanor Lavington’s love of brickwork is no secret and it is instantly evident on this building. There is extraordinary dexterity and variety to the bricks used here – Maccreanor Lavington associate director Dominic Milner reveals that up to 400 brick specials were deployed. There is glazed brickwork, ceramic brickwork, dappled brickwork, flecked brickwork as well as typical London stock brick with further multiple permutations of shade, colour, texture and patterning.

The result is a scheme of rich and varying surfaces, with each permutation helping to give grounding and identity to constituent parts of each building. “It’s a collection of five buildings,” explains Milner, “and the variety of brickwork keeps each building subtly distinct but always reinforces the fact that this is a family of buildings and materials.”

Cleverly, the development also adopts the historical hierarchical tradition of having a more decorated frontage and a plainer, more utilitarian back – and it is variations in brickwork that help achieve this effect. “There’s nothing wrong with having a back,” argues Maccreanor. “It’s a traditional response to an established, 19th-century townscape approach.”

Another historic approach that the development adopts is in the way the brickwork helps articulate these main street frontages. They are arranged into strident vertical bays, with tripartite windows punched between masonry pilasters. Maccreanor is keen to point out that both in scale and proportions the facades are indebted to the warehouse aesthetic of Clerkenwell and Farringdon, an analogy that is indeed unmistakable.

And as with its forbears on the other side of Blackfriars Bridge, it is an arrangement that exudes obvious simplicity and strength. Furthermore, in its willingness to form a reassuring yet unassuming urban backdrop against which the drama of London street life unfolds, the development once again is cleverly aligning itself with the contextual habits and eccentricities of its host city.

Sadly, tall buildings in London rarely seem willing or able to engage with the opportunities presented by the mesmerising intricacy and irregularity of London’s horizontal grain but this development makes some effort to do so. The masterplan features five separate buildings and threads a network of new routes and spaces between each one.

Courtyards

A small public square sits at the base of the tower and the splayed workplaces courtyard is lodged at the rear of the site. The courtyard’s angular awkwardness and plainer brick facades constitute a faithful rendition of the informal irregularity found in the network of concealed, accidental backspaces that lurk behind grander facades across London.

These private spaces do not share exactly frictionless borders with surrounding public realm; somewhat regrettably some of them, including the courtyard, are enclosed behind a series of gates which will only be open to the public during office hours. But the ambition at least of creating a private development embedded within and reflective of surrounding urban grain is commendable.

What is doubly interesting is that the courtyard principle extends inside the buildings too. Brickwork generally continues within entrance lobbies to give internal spaces a more civic and communal aspect. But it is the stunning courtyard within the Circus building where this concept is most dramatically realised.

A soaring atrium extends up a full nine storeys, encircled by a stack of swirling balconies set behind a gridded lattice of brick columns and metal railings. Flats lead directly from the balconies and the full masonry composition is surmounted by a translucent diagrid roof raised above the uppermost floor to allow natural light and ventilation to pour down into the space below. Consequently the atrium essentially works as an external space; a ribbed, insular circus lined with brick that enables the residents entering their flats to feel as if the public realm has swept inside the building and swooped right up to their front doors. It is an inspired introversion of the deck access principle that reinterprets a typical London residential courtyard and lodges it right in the heart of the building.

Height

Everything discussed thus far forms a perfectly convincing application of historic themes found within London’s urban streetscape onto a contemporary building. But inevitably it is the inclusion of the tower itself that forms the most potentially contentious part of the puzzle. Unsurprisingly, Maccreanor is convinced that tall buildings have a role to play in London.

“Tall buildings are here to stay and they can definitely fit into the streetscape. I dispute the claim that they are an alien addition to London’s character. However, I do admit that London doesn’t have the same tradition of tall buildings that we see in North America. But this has little to do with culture and everything to do with the British economics at the time of the New York tower boom at the end of the 19th century and our reluctance to adopt the new technologies that enabled buildings to grow taller.”

The New York reference is pertinent because Maccreanor very much casts his building in the tradition of a typical New York early 20th century skyscraper. “It has a clear base, middle and top and the top is crafted with sprouting finials that pay homage to the Gothic tradition that was such a powerful force during the skyscraper boom.

“Unlike many London tall buildings, it’s also not an object building designed to be viewed in isolation; it is very much embedded into the street at its base, again in the North American tradition,” he says.

Indeed, wisely the tower is almost invisible at its base because of the active ground floor frontages and the dominant marching horizontality of its facades. Also, its envelope is carved by a series of set-backs, all very New York devices. Equally it seems strange now to consider that when Maccreanor Lavington started work on the project, Southwark’s tall buildings policy specifically called for skyscrapers as “stand-alone objects”.

But it does feel rather odd to use the North American skyscraper tradition as a reference point for a building that seeks to establish a new typology of London high-rise. Unquestionably the Americans have always been better at designing skyscrapers than we have and many of the US high-rise themes introduced at Blackfriars, such as the set-backs, the delicately articulated crown and the street level immersion are undeniably positive aspects absent from the vast majority of London skyscrapers.

Nonetheless, Blackfriars Circus undoubtedly offers a stimulating exercise in how London’s traditional architecture could intervene on a building type with which London has always had a difficult relationship. In so doing, the significance of its brickwork facades cannot be overstated; applying London’s trademark material in this relatively new and dynamic way is a masterstroke of typological reinvention.

The brickwork also offers, in Milner’s words, a “modelled masonry structure and aesthetic that provides a solidity and permanence that a glass building never could”. If this structure and aesthetic could be explored on other high-rises with the same contextual empathy we have witnessed here, then this building will do London a service that will extend far beyond the revitalised circus at its base.

Project Team

Architect: Maccreanor Lavington

Client: Barratt London

Main contractor: Barratt London

Structural and civil engineer: URS Infrastructure & Environment UK

Building services engineer: Whitecode Design Associates

Landscape architect: Churchman Landscape Architects

CDM co-ordinator: DBK

Fire engineer: H+H Fire

Acoustic consultant: RBA Acoustics

Interior designer: Blocc

No comments yet